And out of the west there would come at times a great cloud in the evening, shaped as it were an eagle, with pinions spread to the north and the south; and slowly it would loom up, blotting out the sunset, and then uttermost night would fall upon Númenor. And some of the eagles bore lightning beneath their wings, and thunder echoed between sea and cloud.

And what at first was call'd a gust, the same

Hath now a storm's, anon a tempest's name.

from John Donne's The Storm

He scraped a crushed squid from his sandal and kicked a jellyfish off the step. A few fish still flopped helplessly on the paving stones of the temple's court, but hundreds more lay dead. Mairon took care to avoid treading on the slimy animals that lay on the marble stairs, lest he slip and fall.

Shoving hakes and eels aside with his feet, he made his way to the wide court that encircled the temple. The heat of the sun beat down on his brow, raising beads of sweat. Already steam rose from the wet creatures. In no time, the court would be reeking. With the back of his sleeve, he rubbed the sweat from eyes and cast his gaze at the dark clouds that rumbled in the northeast, the storm venting its fury upon Orrostar.

The force of the retreating storm had surprised him. Ever since that Ar-Pharazôn had ordered the building of the armament, the storms inflicting Númenor had become increasingly violent, and this latest had been worse than others, so powerful that it had generated a cyclone like those he had seen roar across the steppes of Palisor many years ago.

The cyclone must have sucked up fish from the sea and then rained them down upon the city. Without a doubt the citizens of Armenelos would consider this rare event to be a dire portent: yet another sign that the Powers of the West now turned their wrathful attention to the Land of the Gift.

Mairon lowered his eyes back toward the steps of the side entrance to the temple where several of his priests clustered, looking out at the mess in the court with disgust and trepidation. He lifted his robes to avoid dragging the hem on dead fish, stepped over a small shark with its gaping jaw lined with razor sharp teeth, and made his way back toward the temple.

The cause of the unusual weather eluded him, and he thoroughly disliked such uncertainty. He recalled when several years ago mariners had returned to Númenor from a far-flung expedition with reports of a large swath of the sea where the waters had become markedly warmer. No one knew what to make of it for nothing of the like had been recorded in the annals of Númenórean sea faring.

The captain of the expedition had been sent to the temple to relay his observations to Mairon who, it was assumed, would be able to explain the phenomenon. Captain Azrakhâd, known for his bravado and spirit of adventure, showed far less confidence when he had entered Mairon's private study. The renowned mariner's eyes had darted around the room, expecting, Mairon thought, to see the devices of sorcery but finding nothing more or less than a scholar's chambers lined with shelves filled with books and scrolls, a few comfortable chairs, low tables and the high priest's wide desk graced by a vase of red roses.

Mairon had risen, put on his most winsome smile, and invited the nervous captain to sit in one of the chairs.

"Will you take a drink?" Mairon had asked, stepping to the sideboard where bottles of liquor were neatly arranged along with several crystal glasses.

"I would, Your Eminence," Azrakhâd said, twisting the edge of his uniform's cloak.

"Cane liquor?"

"That would be welcome."

"Do you mind if I make some additions?" Fear skittered across the captain's rugged face. Evidently the rumors of those from the resistance who had died from mysterious and sometimes abrupt illnesses had reached the captain's ears. That delighted Mairon: Good. These fools should fear me. However, gathering information from men required many tactics, and he wanted this man to be at ease. So he chuckled and reassured Azrakhâd: "No need to worry. I will merely add juices. Perfectly innocent. And by the look of your gums, you could use some lime juice."

Azrakhâd self-consciously covered his mouth, where his swollen gums revealed a mark of the disease that sometimes afflicted mariners on long voyages. Mairon plucked chunks of ice from a small wooden chest, dropping them into two glasses. He poured the dark brown liquor over the ice, followed by a splash of ruby pomegranate juice. He squeezed limejuice into each glass, and then handed one to the captain.

The man tilted the glass back, gulping it all down, which disgusted Mairon. He had meant the drink to be savored. But when Azrakhâd lowered the glass, his eyes had lost their anxiety.

"Tell me what you saw," Mairon said, now sitting in the chair next to the captain. So Azrakhâd proceeded to describe the proliferation of seaweed and tropical fishes that had colonized the once cold waters. He said his sailors had dived into the water, declaring it warm and comfortable, when once it would have sucked the life out a man.

"But most unusual, Your Eminence," Azrakhâd said, his brows furrowed, "was the great upwelling of warm – almost hot – water in the center of this warm sea, as if it were churning up from the deeps."

Mairon had prepared another drink for the captain, asked him a few more questions, and had then dismissed him, telling him that the newly warmed sea was indeed a mystery but that he would have to consider this strange occurrence with care.

Mairon had thought back to a distant time in his life, long before he had come to Arda with the Guardians. He recalled the fascinating teachings of Ulmo and Aulë: Ulmo had told them how warming of a large part of an ocean could affect the weather of a world, and Aulë had taught how the fires under the earth could erupt in fissures of the sea floor. Such natural fissures, Aulë had said, had little effect on an entire sea, but they could be augmented by the arts of the Guardians when they wished to change the climate of a world.

He considered these things while he walked slowly back to the temple. It was not long after Azrakhâd had told him of the warm sea that the weather of the world had changed dramatically, as much as when the Valar had destroyed Beleriand. What once were ordinary thunderstorms had become monsters filled with lightning and blasting the land with high winds, destroying homes and killing men on the hills. More frightening, one of the huge storms that the Númenóreans called "Ossë's Wrath," which had previously bypassed the island, had ripped across Hyarrostar, its terrifying winds flattening its groves of trees. In all these storms, ships were lost along with their crews and their goods.

Azrakhâd was not the only one who came to Mairon for his consultation. The Minister of Fisheries sought his advice when wide streaks of red water – "Uinen's blood" the sailors had named it -- formed and lingered off the coasts of Númenor. Soon after that, people succumbed to a strange illness that began with tingling in the legs, arms and face. Then the afflicted swooned and vomited, and the worst cases – and there were many of these – became paralyzed, dying when they could no longer breathe.

As if that were not enough, a scourge unknown to Númenor had now taken root in the southlands of Hyarnustar: the shivering disease that came in waves upon those afflicted with it, a disease said to be borne on bad airs. Where once Men had turned to the West to try to catch the scent of undying meads, now they made warding signs toward the sunset and pressed feathery grey leaves of wormwood to their mouths and noses in hopes of fending off pestilence.

All of these could be explained by natural causes. Mairon tried to convince himself this was the case, but his methodical reasoning did not allay his doubts. He had been so sure that the Valar had turned away from Men, and Eru had deserted them all – his Children and the Ainur alike – only observing the Mote of Fire unfold to become the vastness of Eä that followed implacable laws but otherwise remaining detached from the minutiae of creation. But Mairon remembered too well the devastation the Valar had inflicted on Beleriand. He shuddered when he recalled the sky turning into flame and the earth shaking when Varda's weapon hit the earth. Ulmo and Aulë's teachings rang in his ears. Were the Valar again trying to manipulate the weather of the world?

Men, however, even in the face of evidence to the contrary, invariably looked to someone to blame. The Númenóreans, once so rational, had become reactive. The King's Men first cursed the Powers of the West, and next pointed their fingers at the Faithful, accusing them of praying to the Valar to visit them with these illnesses. In retaliation, the Faithful accused the King's Men of deliberately poisoning the oyster and scallop beds and casting spells of ill omen over the southlands. These accusations lit yet another fire in the tinderbox of rebellion which Ar-Pharazôn had to suppress. As a result, many prisoners now languished in the dungeons, waiting to meet the holy knife on the altar in the temple. The priests could barely keep up with the sacrifices to the Giver of Freedom. And all this added to the rumblings of the earth and the fumes that now came from the peak of Meneltarma where no one dared to tread.

With the storms, disease, and the tremors from the mountain came doubt among the people of Númenor who had hitherto been so convinced of the rightness of Pharazôn's cause. They questioned the King's policies -- not openly -- but Mairon's informants reported that more and more men throughout the land murmured that the King must repent, for the storms and pestilence were surely signs that the gods had reawakened, and that the Zigûr had not the strength to face the Powers of the West.

He must put a stop to Men's doubts once and for all. Again he looked at the clouds receding into the distance. The storms themselves would provide him with the power he needed to convince the doubters, but he must complete his project first.

Turning his back on the steaming court, Mairon approached the arched doors that opened into the cool corridor that ran through the thick walls of the temple. The gaggle of crimson-robed priests followed him, wringing their hands and murmuring with worry over the bizarre fish-rain.

What hopeless louts, he thought, annoyed by their passive fretting.

He paused in the main chamber, staring at the Altar of Fire where a wisp of smoke floated up to the open main louver of the dome and then at the Altar of Everlasting Life looming above it, all quiet now as if hushed with anxious anticipation.

"Your Eminence?" The familiar voice of his senior acolyte, although subdued, nonetheless echoed throughout the large chamber.

"Yes, Lômir?"

"The fish. What are we to do about the fish?"

Mairon reined in his impatience at such a ludicrous question and replied evenly: "Clean them up, I suppose. Have one of the altar boys sent to the street-sweepers guild with a message that we will make it worth their while to clean the temple court promptly."

"Very well, Your Eminence. What are your directions for today's vespers?"

Mairon ran through his mental list of the incarcerated. He knew each man's name and connections. One was a cousin of Amandil's wife. "Clean and anoint three prisoners from Rómenna for the sacrifices. Be sure that Hrívelo Tundamarion is among them. Your knife is sufficiently sharpened, I presume?"

Lômir's face lost all color. "Yes, Your Eminence."

"Good." Mairon smiled at his senior priest's obvious discomfort. "It would not do at all to have a repetition of the time when it was not."

That had been a ghastly business. Mairon performed the sacrifices by his own hand only four times a year on the high holy days, but he had painstakingly trained the senior priests to slice precisely across the sacrifice's neck, driving the knife fast and deep to completely sever the arteries in the neck so that the blood drained away from the sacrifice's brain, causing the offering to lose consciousness rapidly. It took a strong arm and a keen blade to accomplish this. However, Lômir had neglected his holy blade, letting its edge grow dull.

It had been an ugly sight when the sacrifice gurgled and arched his body from the altar while Lômir had sawed at the man's throat. The congregation had been terribly disturbed. Mairon's wrath at this violation of efficiency had been towering; he had been ready to behead Lômir on the spot, but had waited until Lômir was in his private audience chamber to reach into the priest's mind, grasp the pathways of pain, and twist them slowly, making him writhe in agony on the floor. Judging by Lômir's expression, he had not forgotten this experience.

"I understand, Your Eminence."

"Very well. I will be in the smithies for the remainder of the day and likely into the evening, so I trust you will lead the vespers with your usual grace."

"I will not disappoint you, Your Eminence. May the Giver of Freedom be praised."

"Yes, yes, may the Giver of Freedom be praised," Mairon answered reflexively, spinning around and checking the impulse to stalk away from this absurd man who was so painfully obsequious toward him, but who lorded it over the other priests, the novitiates and the altar boys. Lômir reminded Mairon of one of Melkor's lesser valaraucar, a smoky sycophant who had simpered before the Dark Lord, but who terrorized all others. He had despised the creature.

Keeping his steps measured and stately as befitting his position, he reached the stone stairs that wound up to his quarters. Once out of sight of the priests, he lifted his robes and bounded up the steps two at a time.

He entered the quarters where he now made his residence, easing off his vestments, which he carefully hung or folded, ensuring that all the garments were in their proper place. He pulled on his favorite pair of work trousers, pocked with scorch marks and oil stains and then thrust his feet into his heavy smith's boots. Last he slid a loose soft shirt over his head and slipped out the door.

He sang under his breath while he hurried toward the smithies, his casual song disguising the swift calculations whirring in his mind. He entered the large building where the din of hammers and the screech of metal made it nearly impossible to hear the greetings of his job captains. Once his captains had assured him that today's schedule for the construction of a major section of a hull was proceeding in an orderly fashion, he left the main chamber through a side door that opened to a long corridor. His footsteps echoed off the stone walls.

Only a few more refinements were needed for the device that he had assembled, its design and theory based on Aulë's lessons, which Mairon remembered as clearly as when these had been taught to him. He could complete it today and then assemble it on the pinnacle near the temple in the depths of the night. At the rate the storms were coming from the West and judging by the swell of rumors of those who doubted his power, this work's conclusion could come none too soon. He unlocked the door of his private workshop where the device sat, its outline indistinct but shimmering in the dim light, and he set to work on the finishing touches.

The Altar of Everlasting Life had consumed blood for seven successive days when black clouds towered again in the western sky. Mairon had come to the temple's wide entry and watched the sun slip down behind them, the sky turning red and casting an eerie light over the city. The clouds were so lofty that their heights were flattened in the winds of lower Ilmen, stretching across the heavens like the wings of eagles. As the massive storm approached, talons of lightning streaked through its dark clouds and what had been distant thunder became the growl of an angry beast.

He heard the shouts and cries when fear swept through the city even before the first outriders of wind gusted through its streets and squares. Many flocked to the temple, seeking shelter and reassurance from the high priest of the Giver of Freedom. When the dark wings of the storm spread over Armenelos, those gathered outside in the court cried, "Behold the Eagles of the Lords of the West! The Eagles of Manwë are come upon Númenor!'

Mairon stood firm while he watched the storm rumble toward Armenelos. The clouds above him churned with rage, their color tinged a sickly green. The wind no longer gusted but bore down on the city, shredding leaves from trees, tearing tiles from rooftops, and clawing at walls of stone. Then lightning smote Armenelos, not just a bolt here and there, but many successive ribbons of fire that streaked down from the sky, raking the towers and domes of the city with savage claws. This storm had the whiff of the unnatural -- of the manipulative Valar, and Mairon took it as a personal challenge.

People crowded around the temple gates: men shouted, women wept and children cried, all pressing to enter the safety of the temple. The priests ushered them inside, but Mairon made his way down the steps, the crowd parting around him, and strode out into the court. He kept his nerves in check, the wind flattening his priestly robes against his body, while he walked steadily away from the temple. Then the wind stilled, just for a moment, but Mairon's scalp tingled and the hair on his head rose. He instinctively threw himself to the ground, flattening his body against the paving stones. At that precise moment, the air blazed white-hot and the deafening clap of thunder reverberated through the core of his body.

He willed his heart to slow its frantic beat, thankful that the bolt of lightning had not scorched him. He rose to his feet and turned back to the temple, where he saw the rent in the dome, which was now ringed with a crown of blue fire.

He brushed off his robes and set his jaw. He alternated between cursing Manwë and repeating Superstitious nonsense! in an effort to calm himself. He felt the sting of a small hailstone against his cheeks, the icy pebbles bouncing off stone while he walked toward the rocky pinnacle to the east of the temple. Many eyes were upon him, he knew, and that was just what he wanted.

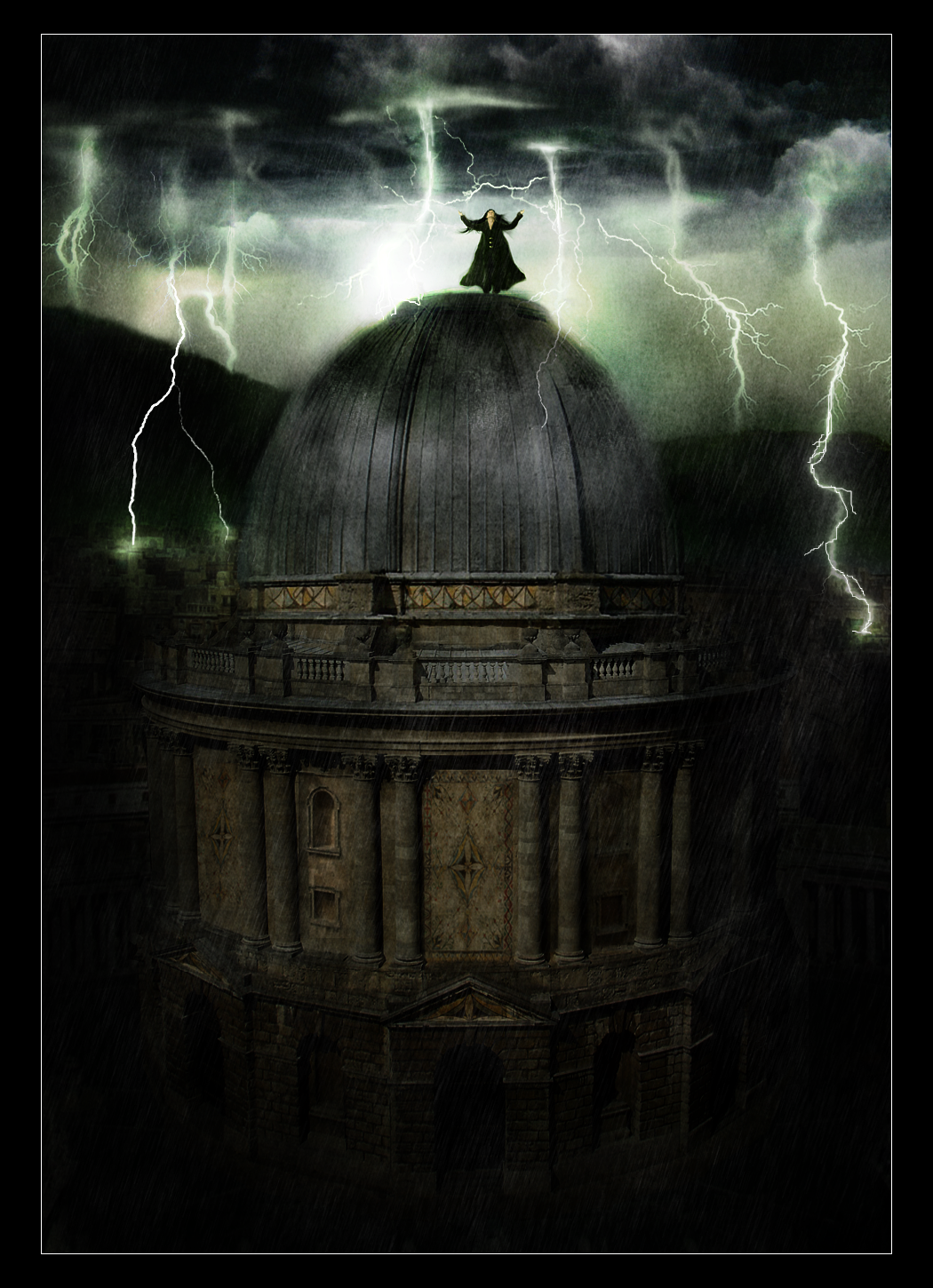

Shrieking like a huge bird of prey, the wind tore at him; his robes tangled around his legs, and he stumbled once. He leaned into the wind to keep his balance, trudging up the narrow path. He reached the height of the pinnacle where his device stood. Squinting, he searched for the subtle rippling of light that was the signature of the device. He feared that he had veiled it too well, but the image of the bars flickered when he set his will to his sight and revealed its position. Still, he knew others, especially from a distance, could not see his craft for he had wreathed his arts around the copper bars so the surface of the metal bent light back to the eye, thus rendering the cage invisible. He opened the door, eased himself inside and waited.

The wings of the clouds descended upon him like a falcon upon a hare. The swirling murk wrapped itself around the pinnacle. Thunder became castigation, and the wind-driven hail stung of punishment.

"I am here, Mânawenûz," he whispered in his mother tongue. Then he lifted his voice, putting the power of the Ainur behind it so that he could be heard over the thunder and the howling wind, and he cried out in defiance: "Come! Come and take me, Eagles of Manwë!"

Mairon spread his arms, turning his palms up and tilted his head back, exposing his throat, just as men's throats invited the holy blade during the sacrifices. He invited the lightning but still he waited.

Then it came. The first bolt struck the cage, wreathing it in white flame. The scent of ozone engulfed him. Mairon felt his heart skip a beat but watched entranced while the charge crackled around the copper bars, pleased and relieved that his device had worked according to theory. The lightning jabbed at him again and again, its jagged claws trying to gain entry into the cage but finding none. Mairon smiled with triumph when the storm's talons were rendered impotent to harm him.

They had thought this storm – this tempest they had named "the Eagles of Manwë" -- was the end of the world. Many had cowered within the temple and screamed when the lightning rent the dome high above. They had prayed on their knees before the Giver of Freedom, his graven image cool, calm and silent, and begged for his deliverance from the wrath of the false gods. But some, even while they chanted the litany of deliverance, prayed silently in their minds to another – to Eru -- who had surely deserted them.

Others had remained clustered at the entrance of the temple, frightened yet fascinated by the massive storm and the lightning. They had watched the Zigûr walk through the wind and hail to the pinnacle. They had watched him climb to the pinnacle and spread his arms wide, his robes and hair whipped wild by the wind. They had seen the spears of Manwë thrown at the Zigûr again and again. Yet the high priest remained unharmed.

After throwing a final spear, the thunder grumbled with frustration, and the storm rolled away toward the eastern seas. The Zigûr had returned to the temple then. They had beheld him with wonder and blanched before his grim countenance. The gathered crowd parted to let him pass into the sanctuary. First one murmured it, then another, then more, their voices swelling as they followed the high priest into the temple:

"He defied the lightning!"

"The Zigûr turned back the spears of Manwë!"

"He is a god. Yes, the Zigûr is a god!"

Mairon turned his smile of satisfaction inward while his congregation clamored around him, keeping his face solemn while he walked toward his seat before the statue of Melkor, but he was well pleased: Let there be no doubt now.

"Ossë's Wrath" – borrowed from Surgical Steel (see The King's Surgeon): a hurricane.

Sauron's device that shields him from the lightning is described here.

Click to view the illustration at full size.