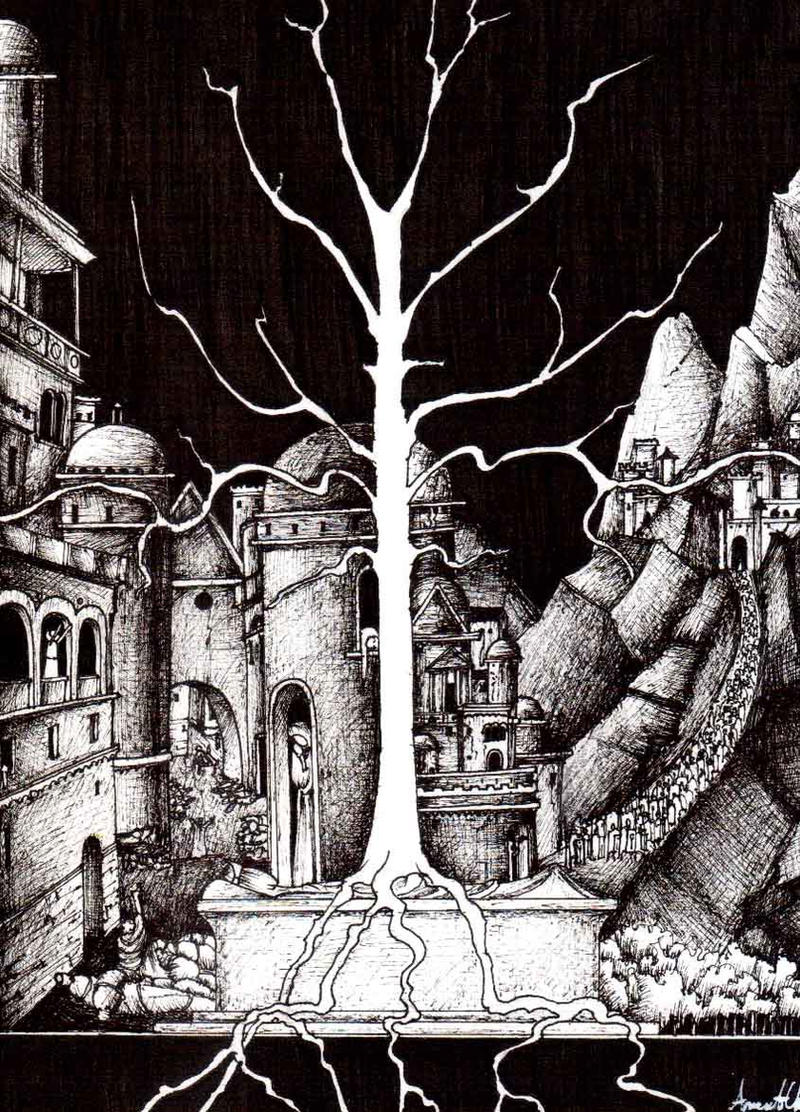

The Plague in Gondor by MirienSilowende

Posted on 14 October 2022; updated on 14 October 2022

This article is part of the newsletter column A Sense of History.

Gondor. When we think of it we might think of Minas Tirith, the great city, the people, the history, the great knowledge. We might think of it as an echo of what was, with the King’s Crown resting in Rath Dinen, the Hallows of the Dead. And you would be right. Gondor was all of those things. There was a slow decline from the great days when the Kings ruled the waves and conquered the South, but there were some events that were pivotal to the decline.

In TA 1636 there was a plague that swept through Gondor and then towards the North, decimating the population. Tolkien referred to it as the second and greatest evil to happen to Gondor:

The second and greatest evil came upon Gondor in the reign of Telemnar, the twenty-sixth king, whose father Minardil, son of Eldacar, was slain at Pelargir by the Corsairs of Umbar. Soon after a deadly plague came with dark winds out of the East.1

This plague was not just a plague, but it was brought by dark winds out of the East. Looking at the systematic destruction of both the northern and southern lines of the Dúnedain by Angmar, chief of the Nazgûl, we can see that Sauron had his strategic hand in this. The plague came just two years after the King Telemnar took the throne, after King Minardil was killed at Pelargir by the Corsairs, headed up by former nobles of Gondor who had left the city due to the Kinstrife.

The king had just ascended the throne and the plague swept through Gondor. The brand new king died, with all his children, who are unnamed. His nephew, Tarondor, ascended the throne. Osgiliath was almost wiped out:

The King and all his children died, and great numbers of the people of Gondor, especially those that lived in Osgiliath. Then for weariness and fewness of men the watch on the borders of Mordor ceased and the fortresses that guarded the passes were unmanned.2

The plague then spread to the North, weakening the Dúnedain in Arthedain and leaving Cardolan a wasteland. The Barrow-wights then move in, whom we meet in The Fellowship of the Ring:

In the days of Argeleb II the plague came into Eriador from the South-East, and most of the people of Cardolan perished, especially in Minhiriath. The Hobbits and all other peoples suffered greatly, but the plague lessened as it passed northwards, and the northern parts of Arthedain were little affected. It was at this time that an end came of the Dunedain of Cardolan, and evil spirits out of Angmar and Rhudaur entered into the deserted mounds and dwelt there.3

This plague was deadly. Osgiliath would have been well-populated at the time, and it had a strategic role in watching over the borders of Mordor. The city of Osgiliath was almost entirely wiped out, which probably left it mostly deserted. The image that we have of Osgiliath as a ruin in the movies would probably be accurate for this period. Most survivors would eventually move to the city where there was more safety.

The new king and his children succumbing to the illness would have been a blow to the stability of the city, and would probably have struck fear into the capital. We know very little about it from Tolkien himself, who mentioned it only in the Appendix. But we can use historical events to look at parallels.

The Black Death is of course the most famous of plagues, happening in 1347-1350, which wiped out a third of Europe’s population. If we apply that to Middle-earth, that would have been a sizable amount of the population who were lost. I would say that the loss of life in Middle-earth was probably comparable.

Many in Europe at the time of the Black Death felt that the plagues were heaven-sent, as a curse. There are similarities in this in Middle-earth as this plague was sent by Sauron in the form of an evil wind. With the recent pandemic that changed the world, I am sure we can all understand how fear affected the people who were living under a plague.

There have been incidents of plague across the world, even in the United States as recently as 1900 where there were cases of bubonic plague. Even in Athens in 431 BCE, there was a "plague outbreak" during the Peloponnesian War, which scholars believe to be an outbreak of typhus or typhoid. The catastrophic impact of the disease on Athens ultimately caused them to lose the war to the Spartans, as the disease raged out of control.4

Giovanni Boccaccio was a writer in Florence in 1348, when plague swept through the city.5 He paints a picture of paranoia and ignorance. People thought that touching the clothing of the deceased would be enough to catch the disease, and they would walk through the streets sniffing perfume to avoid the smell of the dead. People died in the streets, or at home, unnoticed by their neighbours.

Was it likely that Gondor would have ended up like this? It is possible. The city of Minas Tirith itself was centrally placed with good links for trade, which is why the Plague there could spread so easily. People would have been able to escape to other areas in theory, but it was probably discouraged to halt the spread of plague. If Sauron had intended to destroy the city with fear, as he did so many years later with his chief Nazgûl, throwing the heads into the streets during the siege, he would have achieved it.

Telemnar was a new king who had not managed to build enough trust to lead the city. His dying, with his children, may have struck doubt in the city’s hearts. Tarondor ascended and over time would have established his kingship but for a long time the city became insular, less able to control the lands around them. And while they slowly recovered, Angmar and the Nazgûl took more positions in Arnor, ready to almost wipe out the northern line of the Dúnedain.

Tolkien said that this was the second evil to befall Gondor, but was the most evil. I think when we look at its devastating impact on the southern line of the Dúnedain, we can agree with him.

Works Cited

- The Lord of the Rings: Appendix A, "Gondor and the Heirs of Anárion."

- Ibid.

- The Lord of the Rings, Appendix A, "Eriador, Arnor, and the Heirs of Isildur, The North-kingdom of the Dúnedain."

- Thomas R. Martin, "A plague can wipe out peoples—and democracies," The Washington Post, April 14, 2020.

- Boccaccio's The Decameron, TheMiddleAges.net, accessed October 14, 2022.

Wow! This is very…

Wow! This is very interesting. How did I never notice this ghoulish Halloween-worthy topic in the Appendices before?

Oh thanks a million! I've…

Oh thanks a million!

I've always liked this one. There's so much good stuff tucked away in the Appendices, I find! I did some posts covering a King a day from Elros to Aragorn and it was quite the eye opener. The plague era stayed with me. So haunting.

Interesting! I remember…

Interesting! I remember seeing that note about the plague in the Appendices some time ago, but had forgotten about it. It truly would have been devastating and have contributed to the decline of Gondor. I appreciate your touching on the effects of great plagues in our own history and then extrapolating about the effect in Middle-earth. The Legendarium is so rich and complex, isn't it?

Plague and people

While I do vaguely remember reading something about a plague in the Appendices, the impact of it on me was low. This focused look at the timelines and the effect on the kingdoms of both Gondor and the North is fascinating. The instability arising from a dead royal family must have been huge, not to mention Cardolan being wiped out.

It would have been such a…

It would have been such a blow. Osgiliath gone, the Royal family eroded, and then the decimation of the Dunedain in the North line. Cardolan gone was perfect for Angmar to get himself a foothold.

It's the pivotal event that brought us to where we were, the line of the North being brought to simple Rangers, and the barrow wights terrorising the Downs.

You describe well the…

You describe well the devastating impact!

They never quite recovered, did they? At the end of the Third Age, so much of Eriador is wilderness and Osgiliath lies in ruins...

Precisely. They never…

Precisely. They never recovered from this: it was a slow and sure decline from here on in. So many events in Gondor's history can be attributed to their bad decisions but this one was all Sauron.