Sieges in the First and Second Ages by S.R. Westvik

Posted on 18 November 2022; updated on 19 November 2022

This article is part of the newsletter column A Sense of History.

Introduction

Warfare is a cornerstone of Tolkien’s Legendarium. From the great battles of Beleriand in the First Age to the final stand of the Free Peoples at the Black Gate in the Third Age, the great conflicts of Arda are almost inevitably resolved by force of arms. One of the ways in which war is frequently waged in the Legendarium is through sieges—drawn out campaigns lasting years, sometimes decades or even centuries, with belligerents wearing away at one another until one of them finally breaks. The principles of siege warfare are not confined to one time period or another and adapt to the technology and tactics of the era, while the overall goal stays the same: use attrition or a well-planned assault to overcome a static enemy, one who is holed up in a fortress or a city and who refuses to surrender. In this brief article, we’ll focus primarily on understanding sieges through the First and Second Ages of Tolkien’s Legendarium set alongside historical examples from different eras, through which we find many interesting glimpses into the conduct of such blockades.

Setting a siege

In our world, we see sieges throughout the history of warfare. Alexander the Great’s Siege of Tyre, Lebanon, in 332 BCE, for example, is emblematic of the military utility of this practice when well-deployed—it involved a seven-month blockade of the eponymous island, in order to build a causeway that allowed Alexander to weaken the city and breach the fortifications.

When setting a siege, defining its objective is important. The Siege of Angband, for example, was designed to tie up resources. The Noldor could not seize Angband outright—Tolkien does not give the reason clearly, but it is likely a combination of numbers, replacing those numbers as they are depleted, and resources (given that the Elves are, after all, fighting a Vala and his many powerful servants, including other Ainur!). This siege’s objective therefore was to ultimately limit the ability of Morgoth’s armies to venture further south into Beleriand—the best outcome until a better way may be devised to attain the Noldor’s true war aims:

For a long time after Dagor Aglareb no servant of Morgoth would venture from his gates, for they feared the lords of the Noldor… Yet the Noldor could not capture Angband, nor could they regain the Silmarils.1

When it comes to actually carrying out the siege, there are two things to keep in mind: how you strangle the enemy, and then how you break their barricades.

Encirclement

Sieges are effective because they wear down the enemy by cutting them off from resources (food, arms, raw materials, fresh soldiers). This includes encircling the enemy and preventing opportunities for a breakout—a manouevre that would help the defenders penetrate the enemy lines and reconnect to fresh fighters, food, water, fuel, et cetera. During the Siege of Angband, encirclement was a major problem due to the geography:

Nor could the stronghold of Morgoth be ever wholly encircled; for the Iron Mountains, from whose great curving wall the towers of Thangorodrim were thrust forward, defended it upon either side, and were impassable to the Noldor, because of their snow and ice. Thus in his rear and to the north Morgoth had no foes, and by that way his spies at times went out, and came by devious routes into Beleriand.2

During the War of the Last Alliance, however, encirclement was possible because the attackers in this case were able to take advantage of the geography of the Ephel Duath and Ephel Lithui mountain ranges already encircling Mordor on three sides, with very few passes through them:

Then Gil-galad and Elendil passed into Mordor and encompassed the stronghold of Sauron; and they laid siege to it for seven years …3

Isildur committed a dedicated force to prevent a breakout through one of the few weak points in the west:

… Aratan and Ciryon had not been in the invasion of Mordor and the siege of Barad-dûr, for Isildur had sent them to man his fortress of Minas Ithil, lest Sauron should escape Gilgalad and Elendil and seek to force a way through Cirith Dúath (later called Cirith Ungol) and take vengeance on the Dúnedain before he was overcome.4

It is unclear in the text why a breakout to the south, via the Plateau of Gorgoroth, was not possible, especially given that this was the passage towards Nurn, the area of Mordor home to Sauron’s fields and therefore a key resource. It can be assumed that, given the siege is described as “strait”5 in both The Silmarillion and The Unfinished Tales, the Alliance must have devoted significant resources to cut Barad-dûr off from this southern area, and relied on a combination of geography and force of arms to hold the rest of the encirclement.

Bringing down the enemy

Key to any military blockade is the siege engine and accompanying siege train. This refers to the machinery—however primitive!—that is designed to breach the defenders’ defences, while the latter refers to the collective of engines, ammunition, and operators (be they soldiers or vehicles) that move the siege machinery. Returning to the Siege of Tyre, for example, Alexander constructed a causeway and made use of towers carrying catapults and ballistas to attack the ramparts and walls of the city, as well as eventually setting a naval blockade and ultimately using rams and bombardment against a breach in the wall. In the Legendarium, Tolkien gives us an idea both of the tools used in siege engines and the people who operated them:

But in the next year, ere the winter was come, Morgoth sent great strength over Hithlum and Nevrast…and besieged the walls of Brithombar and Eglarest. Smiths and miners and masters of fire they brought with them, and they set up great engines; and valiantly though they were resisted they broke the walls at last…But some went aboard ship and escaped by sea …6

… because unlike Alexander, clearly Morgoth did not set up a successful naval blockade to accompany the siege from the land!

Defenders typically combat the attempts at breaching their fortifications by using ranged weapons and carrying out sorties to weaken the attackers. We already saw that the failed encirclement of Angband made it easy for Morgoth to send out parties through the rear of his domain. However, as happened at Tyre with their naval sorties that harried Alexander’s forces, even a totally encircled city can find ways to send out its soldiers. We see similar efforts during the war of the Last Alliance:

Then Gil-galad and Elendil passed into Mordor and encompassed the stronghold of Sauron; and they laid siege to it for seven years, and suffered grievous loss by fire and by the darts and bolts of the Enemy, and Sauron sent many sorties against them.7

Breaking a siege

The reason that sorties are sent out isn’t just to weaken the attackers, but hopefully to break the blockade itself. This is, however, not an easy task to do from within. Typically, the enemy will need to be assailed or otherwise harried from the outside in order to break a siege. For example, during the 1944 Siege of Bastogne, Belgium, elements of the U.S. Third Army broke through the German lines on 26 December, ending the week-long siege and providing relief to both civilians and the encircled U.S. 101st Airborne troops. In the Legendarium, we see similar external pressure during the siege of Imladris during the War of the Elves and Sauron. Gil-galad called for Númenórean aid in Second Age (SA) 1695; Imladris was established in SA 1697 and was besieged by Sauron at some point between then and SA 1700, the year of the largest Númenórean landings during the war. Sauron’s strategic objective in besieging Imladris was to tie up Elrond’s forces, thus easing his march on Lindon to fulfil his war aim of obtaining the Three Elven Rings. However, besieging Imladris weakened Sauron’s forces by doing the historically ill-advised move of opening a war on two fronts. This made Sauron susceptible to the Númenórean attack when it finally came:

By that time [SA 1700] Sauron had mastered all Eriador, save only besieged Imladris, and had reached the line of the River Lhûn. He had summoned more forces, which were approaching from the south-east, and were indeed in Enedwaith at the Crossing of Tharbad, which was only lightly held. Gil-galad and the Númenóreans were holding the Lhûn in desperate defence of the Grey Havens, when in the very nick of time the great armament of Tar-Minastir came in; and Sauron’s host was heavily defeated and driven back. The Númenórean admiral Ciryatur sent part of his ships to make a landing further to the south.8

Of course, there is an exception to every rule. Arguably the most famous breaking of a siege in the Legendarium is the breaking of the Siege of Angband through the Dagor Bragollach, with the deployment of new, unmatched weaponry—I am here counting Glaurung as a weapon, akin to a new kind of warhead, for example—and a massively rejuvenated fighting force. These circumstances aren’t exactly replicable in our world, but they make for impressive storytelling:

In the front of that fire came Glaurung the golden, father of dragons, in his full might; and in his train were Balrogs, and behind them came the black armies of the Orcs in multitudes such as the Noldor had never before seen or imagined. And they assaulted the fortresses of the Noldor, and broke the leaguer about Angband, and slew wherever they found them the Noldor and their allies, Grey-elves and Men.9

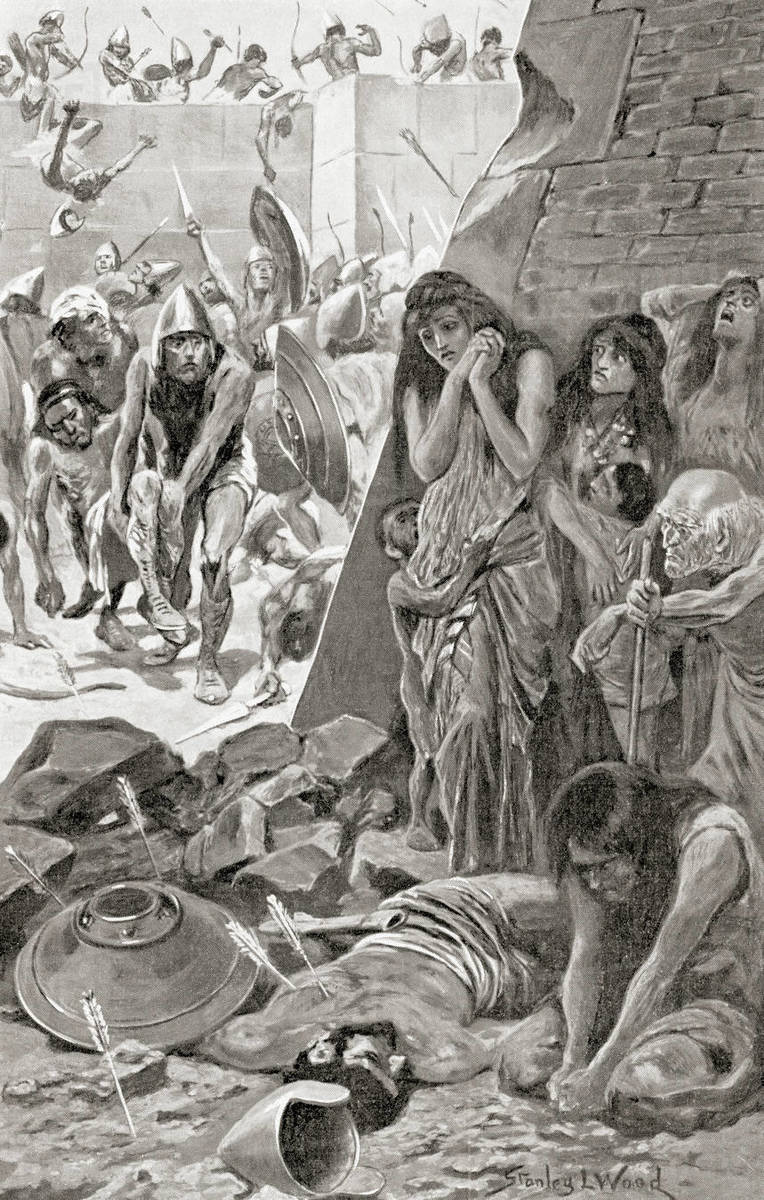

The humanitarian side of sieges

A final word must be said on the impact that sieges have outside the actual fighting of them. Such campaigns tend to be drawn out, with devastating humanitarian impact on the besieged populations, given that what constitutes a “military target” is defined by war aims and strategic objectives more so than whether the inhabitants of the target are members of the armed forces or not. Modern sieges, such as the 1941-44 Siege of Leningrad, the 1992-96 Siege of Sarajevo, and the 2022 Siege of Mariupol, by virtue of their temporal proximity, are the source of well-preserved visual and written evidence, providing some of the most detailed and harrowing witness accounts we have of the effects of sieges on both combatant and civilian populations (including the blurring of these two categories as the war becomes more “total”). In the tales of the First and Second Ages, we do not get such detail, but we do get hints that the humanitarian impact is acknowledged. When Morgoth besieges the Haladin, his raiding force corners civilians not living under united leadership, and only brought together by Haldad:

… and he gathered all the brave men that he could find, and retreated to the angle of land between Ascar and Gelion, and in the utmost corner he built a stockade across from water to water; and behind it they led all the women and children that they could save. There they were besieged, until their food was gone…But at last Haldad was slain in a sortie against the Orcs; and Haldar, who rushed out to save his father’s body from their butchery, was hewn down beside him. Then Haleth held the people together, though they were without hope; and some cast themselves in the rivers and were drowned.10

The seven-day siege is eventually broken by Caranthir, from the north. As we can see, however, this was not before the resources of the defenders—explicitly consisting of non-combatants alongside warriors—were depleted, to the extent that the brutality of the siege eventually caused some of the besieged peoples to take their own lives. The psychological trauma of sieges on civilian populations therefore cannot be underestimated—for more insight into what lack of food can do to an encircled civilian population, the 1941-44 Siege of Leningrad is a horrific yet illuminating exemplar.

Conclusion

The sieges contained within the First and Second Ages are not told with the greatest detail, but contain tantalising elements of real military strategy and practice, from setting a siege to carrying it out. When we consider the sieges of Middle-earth, the setting can help determine the actual technology and resources available for belligerents to use. However, the general principles and effects transcend the historical continuum, and looking at a wide variety of sieges across history can generate a more holistic understanding of the practice and experience of sieges from both the martial and humanitarian perspectives.

Works Cited

- The Silmarillion, "Of the Return of the Noldor."

- Ibid.

- The Silmarillion, Of the Rings of Power and the Third Age.

- Unfinished Tales, "The Disaster of the Gladden Fields," Note 11.

- Ibid.

- The Silmarillion, Of the Rings of Power and the Third Age.

- Ibid.

- Unfinished Tales, The History of Galadriel and Celeborn, "Concerning Galadriel and Celeborn."

- The Silmarillion, "Of the Ruin of Beleriand and the Fall of Fingolfin."

- The Silmarillion, "Of the Coming of Men into the West."

An interesting discussion,…

An interesting discussion, clearly set out and with well-chosen parallels!

Of course, the consideration of humanitarian impact invokes some appalling more recent memories, but that is quite as it should be!

Interesting comparisons

For someone with very little military knowledge, this certainly gives me more idea of what is involved in siege warfare. And of course, while the very real and lasting humanitarian impact doesn't bear thinking about, sadly those who should consider it, seldom do.