Straight Road by Simon J. Cook

Posted on 10 August 2024; updated on 11 August 2024

This article is part of the newsletter column A Sense of History.

The last post, Passing Ships, concluded with the happy thought that Tolkien glimpsed Valinor in the exordium to Beowulf. Maybe. But if so, he was looking on the other side of a quite different prospect. A funeral-ship that returns a corpse over the sea suggests that the king came to his people out of death.1 This is not a comfortable thought, and suggests in turn that the Unknown beyond the Shoreless Sea is hell, the realm of mortal shades.2

Consider the exordium in relation to the centuries. The Anglo-Saxon poet, whose name is lost to us, died more than one thousand years ago. Yet in the days of the poet, the myth of the king who came out of the sea was already ancient. This ancient myth was in those days still recalled, albeit perhaps only as one fragment of a once greater tale, already lost. In this Christian age, the significance of the myth may no longer have been obvious, but our poet had long pondered it. With the innovation of a second ship, a funeral-ship that sails in the opposite direction, returning a corpse over the sea, the Anglo-Saxon poet aimed for an effect that today it seems impossible to recapture.

This exordium is today our best window on this ancient myth. But what is before us is not the ancient myth (the mistake of the friends in the allegory). What we see is an echo, caught by an Anglo-Saxon craftsman and drawn into an exordium for his own story, the new art revealing the ancient myth in a fresh light. But what hidden meaning in an ancient myth of a ship that carried the king to his people is illuminated by its juxtaposition with a funeral-ship that returns his corpse over the sea?

We are caught in an interpretative bind—with knowledge of the art we might learn something of the now lost Anglo-Saxon memory of the ancient myth, and if we knew more about the ancient myth, we might better appreciate the art. As it is, we look upon this jewel of Anglo-Saxon art and know not how to read the vision of the past captured within these fifty-two lines of Old English alliterative verse.

J.R.R. Tolkien is our guide. His starting-point in 'Beowulf: the Monsters and the Critics' is the historical observation that the poem is the work of a Christian telling a tale of the heathen past. In the eyes of an Anglo-Saxon audience, the heroic heathen ancestors who walk in this vanished world of the past appear ignorant of the geography of the world and the shape of the cosmos. Very few of those who once listened to Beowulf would have read for themselves the science of the ancient Greeks, now copied in a handful of Latin texts in Anglo-Saxon monasteries. But we may assume that an audience of the age of Bede, or later, would have known the shape of their world as a sphere.3

Crucial to Tolkien's reading of the Old English poem is his apprehension of the Anglo-Saxon narratorial voice. The Anglo-Saxon poet and audience as it were stand atop the tower and look down on the heathen lords in the halls and mighty heroes under the sky. The narrator talks as one who knows, and frames the heathens on the ground as ignorant—doubly so, as we shall see. For example, Hrothgar declares ignorance of Grendel's origin, but the poet explains that all heathen monsters (including the Elves) are descended from the biblical Cain. And, in contrast to poet and audience, neither Hrothgar nor Beowulf know heaven as an eternal realm awaiting the soul after death—to these heathen lords and heroes the sky is just the sky.4 The Anglo-Saxon audience heard the words of the poet, saw before them a vision of their heathen ancestors, and recognized themselves as a little more settled and gentler, and—at least by contemporary Continental measures—far better educated.

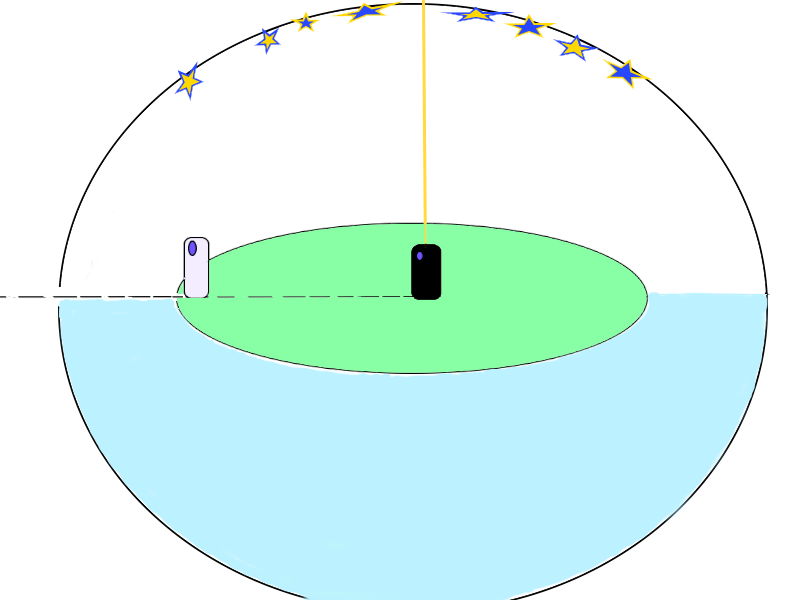

When the Anglo-Saxon audience looks up at the night sky, they see the heavens. Technically, they look up and see a great crystal orb, the revolutions of which slowly move the stars through the sky. What is more, from ancient Greek authorities, a very few of whose writings could now be read even in the British Isles, they know that this final sphere of the cosmos is the very edge of Time, the border of the cosmos beyond which is Eternity. When these educated Christian folk hear a poet tell of a heathen funeral-ship sailing on a horizontal road into the West they know—and they know that their heathen ancestors did not know—that the reality is more like a right-angled ascent. After the death of the body, the shade does not pass over the sea to hell on the horizontal but, rather, the soul ascends on the vertical out of the circles of the cosmos (the gold line in the image).

From an orthodox Christian point of view in the eighth century, the ship-burial is pure heathen error, borne of spiritual confusion and geographical ignorance. Nevertheless, to an audience who honored their ancestors and were predisposed to discern nobility in the brave heroes of old, the passage of the funeral-ship into the horizon makes for a powerful image of the escape from Time, as death is now framed. Passage into the horizon where the setting sun sinks over the western ocean is recognized as heathen error—and passes into metaphor.

But this orthodox reading of the exordium solely through the circular lens of the round cosmos leaves the first ship unaccountable mystery. The second ship cannot sail to hell, and not only because heaven and hell are not within but outside Time. The geographical fact of the matter is that the world is round and sailing into the western ocean leads eventually not to hell, nor even to Valinor, but back home again. But if the world was always round, this first ship that sailed out of the sea has no known origin in the world. So what does the myth mean?

The noble but brief exordium. Places us just this side of the ancient myths and beginning: we are just in history. The ship burial.5

This is the textual anchor of this series of posts, recording a moment in which Tolkien pivots from scholarship to fantasy. Three sentences, an isolated note in a bundle of academic notes that belong with two earlier versions of 'Beowulf: the Monsters and the Critics', material edited by Michael Drout and published as Beowulf and the Critics (2002). Drout dates the material to the summers of 1933 and 1935.

The second sentence gives terse expression to a reading of the exordium to Beowulf. Within the sentence is a framework that saves the appearances of the two ships of the exordium by redrawing the shape of the world in Time. This solution is conceptually complex and analytically subtle, and it would be a tall order to pull out its meaning from the sentence unaided. But we are recipients of an Elvish gift. Quite possibly in the winter that followed its summer composition, Tolkien unpacked the meaning of this sentence for himself.

In a nutshell, he posited Atlantis as the origin of the first ship of the exordium.

The Fall of Númenor was composed early in 1936.6 Much could be said about this Elvish myth, beginning with The Lost Road—the unfinished novel of time travel bound up in its composition. In this post, my only claim is that the Straight Road, as drawn by the Elvish myth, provides the key to a curious reading of the exordium to Beowulf.

You all know the story of how the world was made round. Númenor fell into the ocean as the flat-world was divided into two portions, with ours bent into a sphere to make a round world. On the rounding of our world the Straight Road appeared in history, a memory or afterimage of the ancient line of the world. Some in history possess straight-sight—they can see this lost road of myth, but few recall the meaning of what they see.

We can read the story of Elendil's escape from the ruin of Númenor as an imagination of the larger tale out of which the first ship of the exordium is drawn.

Out of a mythical ‘beginning’, the Straight Road is drawn in history by the passage of Elendil's ship, even as it is lost in its wake. Elendil sails into history on the Straight Road because he sails out of the myth of the 'beginning', an origin just on the other side of history. The way the Elves frame it, no (mortal) ship could return on this sea-road, which vanishes into memory even as it is sailed by a mortal just this once.

The Fall of Númenor posits, prior to the turn to joy of those who behold the coming of the king to our shore, a catastrophe on the other side of the 'beginning'. But Elendil escapes out of death and arrives in Middle-earth as king. The Elves tell of no funeral-ship for Elendil, whose march to his doom in Mordor is considered next month. Nevertheless, in their preamble to this legend of Beleriand, the Elves draw for us the historical ship-burials recalled in Beowulf . A heathen ship-burial, from an Elvish point of view, is a misunderstanding of the Straight Road, the meaning of which has been redrawn by mortal fantasy, as it were, in a dark mirror.

From a mythical point of view, the situation at the dawn of legendary history is that many of the Númenórean exiles have straight-sight and can see the ancient line of the world, but these exiles, who have fallen out of myth and into history, still desire immortality. No longer seeking an immortal realm in life, as had their mythical ancestors, they do so after life:

And in the fantasy of their hearts, and the confusion of legends half-forgotten concerning that which had been, they made for their thought a land of shades, filled with the wraiths of the things of mortal earth. And many deemed this land was in the West, and ruled by the Gods, and in shadow the dead, bearing the shadows of their possessions, should come there, who could no more find the true West in the body. For which reason in after days they would bury their dead in ships, or set them in pomp upon the sea by the west coasts of the Old World.7

The doom of tradition is to be forgotten, recalled only in the folly of a counterfeit.

By virtue of their own tale, the Elves are mythical beings who do not belong in history, and the Anglo-Saxon poet names them monsters, descendants of Cain. Nevertheless, when these mythical beings not doomed to die look upon mortal history from their end of things they see much the same vision of doom and gloom as did the Anglo-Saxons from (in their day) the other side. The 'Anglo-Saxon poet's view throughout was plainly that true, or truer, knowledge was possessed in ancient days (when men were not deceived by the Devil)'.8 The Elves articulate the ‘philosophy of history’ of the Anglo-Saxon poet, only framed from the other side. They give us a mythical ‘beginning’ and the first ship and, with their account of the second, the historical fall of memory into confusion and darkness. From the top of the Anglo-Saxon tower, the poet takes this mythical ship and juxtaposes it with a heathen ship-burial to make a symbol of the doom of tradition.

Between the first and the second ships of the exordium is the rule of one mythical king and a forgetting of the meaning of the Straight Road. Heathen error, as the Elves tell it, arises not because of a wrong so much as an out-of-date geography. The memory that is the Straight Road is still seen, but a memory of the world as it was in a mythical age that has passed is mistaken for an image of a road into the future. From the ship-funeral of the exordium we are invited to see how the meaning of the ancient myth has been forgotten in the days of the poem, when heathen heroes like Beowulf walked to their doom in Middle-earth.

The heathen heroes of the exordium who mourn the passing of their king do not know where his ship will arrive. Appearing to gaze into the horizon with straight-sight, and looking in the direction of what today we know to be Valinor, they are filled with doubt and uncertainty. Yet they have just sent a corpse over the sea, and we must presume that they have some notion of returning their dead king on the Straight Road to hell, the realm of mortal shades.

These heathen heroes are doubly ignorant, and the second ship of the exordium has a dual symbolism. On the one hand, they do not know that the true escape that is death is a vertical ascent of the soul out of the circles of the cosmos, and look rather on a horizontal passage of the mortal shade into the West. On the other hand, they have forgotten that this western sea-road of myth was lost long ago, and is now only a memory. From a Christian perspective, the funeral-ship of Scyld Scefing is a symbol of heathen errors on matters of geography, astronomy, and theology, but may serve as a metaphor. Yet Anglo-Saxons who climbed the stairs of the tower may have found in the juxtaposition of the two ships seen sailing on the sea a symbol of the fall of their native tradition into darkness.

The Fall of Númenor tells only of the first ship of the exordium. Having told the myth in full, Tolkien had no need to juxtapose the mythical ship of Elendil with a funeral-ship in order to draw out the meaning of the myth. So instead, in the second version (said by Christopher Tolkien to have been penned soon after the first), Tolkien adorns his myth with his own artistic innovation, in which the funeral-ship of the exordium appears as it were in a mirror. The Elves tell that

many of the Númenóreans could see or half see the paths to the True West, and believed that at times from a high place they could descry the peaks of Taniquetil at the end of the straight road, high above the world. Therefore they built very high towers in those days.9

Towers were built by noble heathens at the dawn of history. In those days, many could see the Straight Road with their straight-sight, and some had not forgotten the meaning of what they could see, and built towers.

When you have the myth down from the beginning, and reckon that you read the Anglo-Saxon art right, you are in a position to replace the old poet's artistic innovation with an artistic symbol of your own devising. As a mirror of heathen ship-burial, Tolkien gives us a noble tower with a view over the sea.

Dedication

Dear Thomas P. Hillman, whose Pity, Power, and Tolkien's Ring: To Rule the Fate of Many (published by Kent University Press in Ohio in 2023) I now hold in my hands, I hope you will accept this dedication, offered in thanks for a treasured gift, and also in recognition of our friendship, fine discussions of Tolkien, and common pain as authors. The dedication serves in place of a Facebook post with an image of me holding up your book. As I see it, social media thumbs and the like are signs of fallen readers, social media users who deem likes and shares a substitute for reading the work. Alas! We live in an age when authors bow to readers who do not read. Where is the close-reader of yesterday? We have fallen into shadow. Thomas, along with the dedication, I must ask you also to accept an apology from another fallen reader. I would beg your pardon for my many shortcomings as a reader of your most excellent book, shortcomings of the past (in manuscript), shortly in the bath, and to come, even beyond the day after this shiny new copy disintegrates in my hands.

Works Cited

- Tolkien's two tales of the coming of the king on a ship retain this suggestion of a passage out of death. Elendil sails into exile out of an apocalypse, the death of his island home, the ruin of Númenor. Passage through death is the road under the mountains by which Elendil's heir arrives at the ship that will sail him on a sea-wind upriver to Gondor, as recounted in 'The Passing of the Grey Company', the first book of The Return of the King.

- Hell is a Germanic word, meaning 'the "hidden land" of all the dead', 'ultimately related to helan "conceal"'. Beowulf: Translation and Commentary, 298 and 167.

- The image Fusion accompanying the post reveals the gap between Tolkien’s Beowulf criticism and his final myth of the Elves, which was intended as a tale in its own right and, as such, made for a modern audience who lived several centuries after Nicolaus Copernicus. In the image: Above the Straight Road (the dashed horizontal horizon) is the world of Tolkien's Beowulf criticism: an Anglo-Saxon vision of the heavens as the round cosmos of Ptolemaic astronomy. Below the horizon is the rounded world of the Elvish myth. For us today to climb the enchanted staircase that is Beowulf we must first adjust our sense of history so that we apprehend the universe as do the Anglo-Saxons of the age of Bede. We must read the poem as if a round spherical cosmos and an unmoving Earth at its center is newly received scientific fact. By the same token, stepping out of Tolkien’s Beowulf criticism and into the secondary world of his own stories, this ancient image of a circular cosmos vanishes, leaving only the world made round at the origin of history.

- See "Beowulf: The Monsters and the Critics", 45, 46 notes 20, 25.

- Beowulf and the Critics, ed. Michael Drout (Tempe, AR: Arizona Center for Medieval and Renaissance Studies, 2002), 423.

- On the dating of The Fall of Númenor, see John Rateliff, "The Lost Road, The Dark Tower, and The Notion Club Papers: Tolkien and Lewis's Time Travel Triad"' in Tolkien's Legendarium: Essays on The History of Middle-earth, ed. Verlyn Flieger and Carl E. Hostetter (Westport: Greenwood Press, 2000), 163.

- History of Middle-earth, Volume V: The Lost Road and Other Writings, The Fall of Númenor, "The first version of The Fall of Númenor" and "The second version of The Fall of Númenor," §10.

- "Beowulf: The Monsters and the Critics," 46, note 25.

- History of Middle-earth, Volume V: The Lost Road and Other Writings, The Fall of Númenor, "The first version of The Fall of Númenor" and "The second version of The Fall of Númenor," §11.