Spiral Staircase by Simon J. Cook

Posted on 5 September 2024; updated on 5 September 2024

This article is part of the newsletter column A Sense of History.

Er muss sozusagen die Leiter wegwerfen, nachdem er auf ihr hinaufgestiegen ist.

Ludwig Wittgenstein1

Tolkien's 1936 allegory of Beowulf tells of a man who made a tower of some old stones, of descendants who complain about the tower's proportions, and of friends who demolish it the better to inspect the stones. Nobody enters the tower. The concluding line laments that 'from the top of that tower the man had been able to look out upon the sea.'2 But the only way that the poet might have arrived at the top of the tower that we have actually observed is by building it, stone by stone, storey by storey.

One can only presume stairs. Hidden inside the walls of this tower is surely a staircase. Tolkien is talking about a work of art, so we are not looking at a makeshift ladder running from the ground to the top of the tower. I presume that the Anglo-Saxon builder fashioned an internal spiral staircase (their use dates back at least to Roman times and Anglo-Saxon builders made use of them).

But it is not so simple. First of all, did the staircase lead all the way to the very top of the tower, or did the stairs stop at the last storey so the builder indeed employed a ladder to climb out onto the roof? Second, we know that the tower was designed to lead an Anglo-Saxon audience up to a view down on the lost world of their heathen ancestors; so, this staircase is a time machine, but we lack a neat diagram showing how it works. Thirdly, how did the builder hit upon the design of this enchanted tower? Are we looking at an Anglo-Saxon invention, or at a very ancient blueprint discovered by the builder within one of the old stones?

The tower rises from the green grass of some Anglo-Saxon kingdom and allows an audience to look down on the world of ancient Northern imagination. To climb the staircase within the tower is to travel back in time, and I infer that the higher one climbs the further back in time one can see. A builder who can make such a staircase holds the secret of time travel. Obviously, our goal is to discover this secret. But if we cannot even describe an ascent of the staircase, how can we hope to build our own flight of stairs? As things stand, we seem to be looking at this tower from the wrong point of view.

We are told that from the top of the tower the builder looked out on the sea. My inference that the higher one climbs the further back in time one can see might be pictured as a series of windows running up the east and west faces of the tower, none of which command a view on the sea—that view requires clambering, maybe by aid of ladder, out onto the rooftop. Use of a ladder is suggestive of a foundation of the Anglo-Saxon art, as I'll explain in a moment. But I'm going with a simpler image. Employing capitals (where Tolkien did not), I posit that from the highest window on the west at the top of the internal spiral staircase, and only from this window, one may look with the straight sight of the Elves upon the mythical Shoreless Sea; all lower windows on the west reveal a sea-view, but its mythical quotient vanishes from sight as we descend the stair and what comes into focus ever more clearly is merely the sea.

I am going with the hypothesis that from the topmost western window of the tower the builder saw the Shoreless Sea and the Straight Road of ancient myth, and did so with the 'straight sight' of the Elves. We do not yet have a blueprint, nor even an image of staircase ascent. But opening up the poem, we can begin to make sense of descent.

Descent

In the first instance, the concluding line of Tolkien's allegory simply positions us in space and time—at the very top of the tower, and so looking out on the most ancient view that this tower can provide. The most ancient view glimpsed in Beowulf is the arrival of the first ship of the exordium. Such I have named this ship in these posts; but in the lines of the poem this first ship is seen second, and only then, as it were, through a glass darkly.

The mythical king Scyld Scefing is introduced already a foundling on the shore. The ship on which he arrived is glimpsed only after his death, as the poet turns us out to sea for the first time to tell of the ship-funeral, and recalls in passing 'those' unnamed allies beyond the Shoreless Sea who sent the king to his people at the beginning.

The sea is first framed in the poem only in this second part of the exordium, the funeral. The heathen lords and heroes on the ground whose mourning and uncertainty concludes the exordium appear confused about the shape of their world—unsure of what actually is on the other side of the horizon. They recall that the king sailed out of this sea, and that unnamed 'others' sent the king over the sea, and it is said that this funeral-ship is what the king asked for. Yet the very idea of a funeral-ship returning a corpse over the sea suggests a fundamental confusion about the nature of the western ocean, be it curved or straight.

My suggestion is that the poet does not begin the poem with that view on the sea with which Tolkien concludes his allegory. The poet indeed positions the Anglo-Saxon audience before the highest window on the west, but directs their gaze not out to sea but rather at the shore, and then turns their gaze further inland. In other words, Tolkien intimates that the poet has seen something out of this window that is not shown to the audience.

Here is where it is tempting to imagine a ladder leading out onto the top of the tower. For a view from the top of a tower is a view that is not found within it, and the idea of a final step, surmounted by ladder after the spiral stair has come to an end, does draw out the foundational technique of the Anglo-Saxon poet that Tolkien is circling. But in this preliminary exposition of the architecture of the tower I have opted for economy over ingenuity. The simplest image of what Tolkien is pointing to in the poem is drawn by one window, the highest window of the tower, a window in which the poet has previously looked out on sea, but makes use of at the start of the poem only to frame the shore.

The poet begins with the king a foundling, tells of his warlike deeds and his heir, that his end came, and only then turns us to the sea with an elaborate account of a funeral. My suggestion is that with this ship-funeral, we have made a full turn of the stairs and are again looking out of a western window, the third highest window of the tower. Only now does the poet frame a sea-view for us, and only in doing so reference the mythical ship that sailed out of the sea at the beginning, which the poet saw clearly from the very highest window.

So, my idea is that when Tolkien concludes his allegory by placing the poet on the top of the tower and looking out on the sea, we are being pointed to a view on the Sea that is not found within the poem and yet is foundational—if one may use this term upside-down—to the views that unfold before us as the story of Beowulf is told.

Consider the sea in relation to the story of Beowulf. The fifty-two lines of the exordium tell of the mythical king who came out of the Sea, subdues his enemies, leaves an heir, dies, and is returned over the sea in a ship-burial. Then we rapidly descend four generations, to the legendary days of the mythical king's great-grandson, Hrothgar, who is an old king when the young hero Beowulf sails into view. The following 3130 lines of the poem tell of the great deeds of the young hero Beowulf, of his final battle—an old king fighting a dragon, and conclude with Beowulf's heathen burial in a great barrow raised by the sea; Beowulf has left no heir, and his mourning people are doomed.

The way of the poet is to contrast youth and old age and frame one life in relation to the sea. From the point of view of the tower, this frame implies a circular turn. We begin looking at the shore, turn inland to watch the victories of youth and then step into the inevitable defeat, and on arriving at the end discover that we are again looking out on on the sea by way of a heathen funeral in a great barrow.

A life is lived in time, and each circular turn is a tale of years, a descent in time that is a step towards the present that awaits on the green grass of the hill on which the tower stands. The turn from the sea to the view inland and back again is no circle performed on the same floor of the tower but, rather, a spiral-turn down the steps of an internal staircase.

This spiral staircase is hidden within the allegory. An erudite riddle to be teased out of the story by readers of Beowulf who have a taste for this kind of thing. One does not need to see the staircase hidden inside the tower to follow the argument of 'Beowulf: the Monsters and the Critics'. Nevertheless, seeing the staircase in the storytelling of the Anglo-Saxon poet does orientate one nicely to Tolkien's reading of Beowulf.

Recall that my reading presumes a distinction between the sea and the Sea. All windows on the west in this tower command a sea-view, but only from the top of the tower is the Shoreless Sea seen for what it is. Already from the first western window through which we gaze on the sea in the poem (the third highest of the tower), the Shoreless Sea is perceived only in confused form by the heathens on the ground. Through all subsequent windows on the west the sea is seen shimmering, and maybe it calls to us, but only at the very top of the tower does one see the sea with the eyes of the Elves, looking with 'straight sight' down on the Straight Road that leads over the Shoreless Sea to Valinor.

Straight Road

One who does use a ladder and clambers onto the rooftop of this tower may look out to sea, then turn around and gaze inland. Be it from the roof or from the highest window, however, one who watches the good king sail out of ancient myth must turn around and descend some steps to watch as this legendary king draws the Straight Road with his march inland to doom.

My August post pointed out that Elendil's ship draws the Straight Road in history as it sails out of a mythical origin. 'But there remains still a legend of Beleriand.' Arrival on the shore is not the end of the road for Elendil, who unlike Scyld Scefing is buried in a tomb. The Elves conclude their mythical account of the beginning of history with the legend that we today capitalize as the Last Alliance. Elendil, the Elf-friend, took counsel with the remaining Elves of Middle-earth and made a league with Gil-galad, the Elf-king who was descended from Fëanor:

And their armies were joined, and passed the mountains and came into inner lands far from the Sea. And they came at last even to Mordor the Black Country, where Sauron, that is in the Gnomish tongue named Thû, had rebuilt his fortresses. And they encompassed the stronghold until Thû came forth in person, and Elendil and Gil-galad wrestled with him; and both were slain. But Thû was thrown down, and his bodily shape destroyed…3

The complete journey of Elendil, sea and land, joins the stories of Scyld Scefing and Beowulf. Elendil travels a single road that enters the western frame somewhat above the horizon of the newly rounded world and, having given us the original arrival of Scyld Scefing in history, continues straight on, past the shore, anticipating the later march of Beowulf to his doom.

Elendil walks the entire Straight Road in the course of one lifetime.4 One who stands on the top of the Anglo-Saxon tower and watches his arrival on wings of storm must turn around and descend a stair to follow his inland passage to doom, with the great battle in Mordor observed from the highest window of the tower.

Since this first passage out of a mythical origin and down the Straight Road in history, the heroes like Beowulf, and you and I after him, walk only the inland portion of this road and fight our last battle alone. To everyone after Elendil's sea voyage, the sea portion of the Straight Road seems like a fairy-story, as does the idea of an Elvish friend, and maybe even the idea of a friend who fights the inevitable final defeat by our side. Yet even a tale of two Hobbits who walk the inland portion of the Straight Road all the way to doom and back again appears to us today a fairy-story. Only with the Anglo-Saxon's story of the hero Beowulf do we step out of fairy-story and into the reality of our own mortal lives in history, in which we walk the last part of the Straight Road to doom alone.

Be it told as fairy-story or heroic elegy in a mythical mode, we may watch the whole story of one mortal's march inland to doom from the same high window in the tower. But to observe this mortal life as a whole we must turn around on the staircase and look out on the sea. To follow the journey of first Scyld Scefing and then Beowulf, to watch the whole journey of Elendil on the whole of the Straight Road, to follow Frodo and Sam there and back again and then over the sea, the watcher in the tower must turn around, descending a stairway.

Elvish Design

Presuming a spiral staircase within the tower has helped make sense of descent, yet we remain in the dark as to the mode of Tolkien's Beowulf criticism. Within this metaphor, the way of the critic is upwards, but all we know for sure is that the tower was built of old stones. With such raw materials one must start on the ground, or foundations under it, and build slowly upwards towards the sky. Critics are not builders, but the friends and descendants who remain on the green grass of the present outside the tower are not good critics. The good critic enters the tower and climbs the staircase. But who among us can say how such an adventure in criticism would appear, how the voices of the critics would sound, to what end their adventure?

'Beowulf: the Monsters and the Critics' does not give us Tolkien's Beowulf criticism, only a framework for it. This celebrated academic paper, delivered as a lecture in London in November 1936, is a defence of the art of the Anglo-Saxon poet, intended to overturn the withering criticism of W.P. Ker, which had stood as sober orthodoxy since 1904. As such, 'Beowulf: the Monsters and the Critics' is a rhetorical performance consisting at its core of a powerful demonstration of cultural fusion introduced by an illustration of the kind of mythical art that Tolkien is defending. This post concerns the illustration, the allegory of the tower. With the next post I hope to outline the demonstration, and it is not impossible that it sheds light on how a critic climbs the hidden staircase of this metaphorical tower, but don’t hold your breath.

Concluding this post, I put aside the search for Tolkien's Beowulf criticism and consider only the original use of this kind of staircase, which entails picturing Elves on the stairs. These towers-with-sea-view appear in Tolkien's writings of 1936 first when the Elves tell of the legendary exiles of Númenor, and again when Tolkien tells an allegory of the making of Beowulf. They are constructions of stone fashioned by mortal hands; nevertheless, they first appear in an Elvish account of mortal history, and reappear in its great sequel as Elf-towers, the tallest of which houses the singular Stone of Elendil. These towers reveal the pattern of mortal history, and they are gifted to us for our usage, for a time, but the blueprint is Elvish and their design reveals an Elvish perspective on our human condition.

On the level of allegory, or metaphor and story, paths from the 1936 story to a Hobbit sequel begin to open up before our eyes. We are facing the possibility that one of the stones that the Anglo-Saxon poet found in a heaped pile at the beginning of the allegory was an Elvish Stone, or at the very least was sufficiently ancient that a keen eye might discern within its mysterious depths some lost Elvish blueprints. The possibilities of fanfiction glimmer as a Ptolemaic orb crashes into the story, cracks the external staircase of an inland tower, and is picked up by a Hobbit, a good critic about to reveal the face of a foolish friend! Please keep a lid on such fantasies, if possible, at least for the moment. Stepping into a tower and ascending the stairs with the eyes of Hobbits might be an adventure worth recounting. But in concluding this post I am chasing clarity of vision, and wish to behold our staircase with the eyes not of Hobbits but of Elves.

'On Fairy-stories' invokes 'the oldest and deepest' of our mortal desires—the Escape from Death, and briefly pictures our fairy-stories in an Elvish mirror. Tolkien writes, 'Fairy-stories are made by men not by fairies. The human stories of the elves are doubtless full of the Escape from Deathlessness.'5 Lúthien enchants her hair to escape imprisonment from her high chamber within an Elvish tower, so pointing immortal Elves down to the road to mortal death. Maybe other stories were drawn on as well, but I speculate that Lúthien's improvised escape from a tree inspired some later Elvish artist to picture mortal history by the cunning device of an internal staircase hidden within the walls of a stone tower. Against the measure of one single strand of enchanted Elvish hair, the revolutions of the spiral staircase mark out the spiral cycle of generations that is the descent of mortal history towards the present.

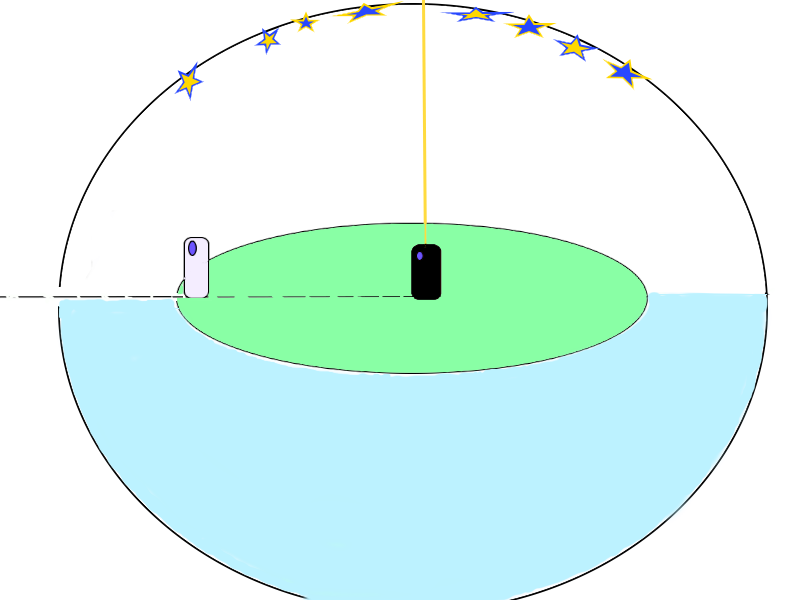

The image Fusion was drawn to illustrate the point of view of the Anglo-Saxon poet and audience who look down on the Straight Road from high up in the tower. The Ptolemaic crystal orb that surrounds the world is unknown to their heathen ancestors on the flat ground. Outside of this cosmic circle, the Anglo-Saxons picture an Eternal realm, to which the mortal soul ascends after death to come face to face with God, who dwells beyond Space and Time. But this passage of the mortal soul as a vertical ascent to heaven or descent to hell outside the walls of the world is unknown to anyone on the ground, including any Elves who have not yet faded.

In place of this gold line that draws the ascent of the mortal soul after death, which nobody in this secondary world can see, the Elves fuse the circle of the newly rounded world with a vertical line picturing their own unfaltering descent in time to draw the cycles of the generations that mortals know as history. The spiral stairway hidden inside the tower is an image of mortal history drawn from an immortal perspective.

Picture some heretic loremistress of old explaining the staircase of the tower with the aim of illuminating mortal-stories. The song of her words carries her Elvish audience to the topmost chamber and the highest window of the tower, through which they observe with straight sight the sea passage of Elendil, his meeting with Gil-galad, and—turning around and descending the stair—the march to Mordor and final battle with Sauron. Through the second highest window of the tower, the Elves gaze inland, watching spellbound as both Elf-friend and Elf-king are slain. These Elves are not strangers to the death of their kin and have some notion of a western passage of the slain Gil-galad, but the loremistress directs their attention to the Elf-friend, whose dead body is buried in a tomb and whose story is now over. Yet this mortal king leaves an heir, who has a story of his own, and the tour party descends another turn of the stair.

Other things being equal, Elves walk a road as long as the time of the world itself. Until the spiral of the mortal generations is drawn out before their eyes, they likely do not notice the ebbs and flows and changing tides of mortal history. But this Elvish tour party on the spiral staircase are beginning to apprehend how each turn of the winding stair marks the passage of another mortal generation in history, and they know that these towers may be built very high and that from where they stand the stairway descends a long way down. These Elves remark one to another on how the mortal generations come and go, crooked or straight but all turns on the stairway, the western windows marking death almost as rapidly as the falling leaves mark the autumns of Middle-earth.

The tower reveals to the Elves our human condition in Time. The Elves who have walked down a straight stairway since their own mythical beginning observe that each turn of our spiral staircase measures the tale of years of one more mortal generation. To the Elves, who remember, each generation that makes its turn on the staircase appears as if from nowhere, and must learn anew the memories of the views on the world given from windows now high above. The Elves observe that the passing generations no longer recognize the Sea in the view from the lower western windows. They step out of their tower tour with a little more wisdom concerning the doom of tradition among mortals.

This image of mortal history as descent by spiral turns is mirrored in the asymmetry of sea and inland views from any height within the tower. When we look out on the sea we recall our past, but only in the half-dream of a fantasy. Our memories of our own lives are a jumble of confused fairy-stories and most of what once was we either never noticed or have utterly forgotten. As for historical memory, it must be learned anew by each generation, is easily confused and corrupted even within one generation; and requires the art of the Elves to recover. On the other hand, a descent of the stair that brings doom into view sobers us all, mortals and Elves alike.

Appendix

Tolkien’s 1936 allegory:

A man inherited a field in which was an accumulation of old stone, part of an older hall. Of the old stone some had already been used in building the house in which he actually lived, not far from the old house of his fathers. Of the rest he took some and built a tower. But his friends coming perceived at once (without troubling to climb the steps) that these stones had formerly belonged to a more ancient building. So they pushed the tower over, with no little labour, in order to look for hidden carvings and inscriptions, or to discover whence the man’s distant forefathers had obtained their building material. Some suspecting a deposit of coal under the soil began to dig for it, and forgot even the stones. They all said: 'This tower is most interesting.' But they also said (after pushing it over): 'What a muddle it is in!' And even the man’s own descendants, who might have been expected to consider what he had been about, were heard to murmur: 'He is such an odd fellow! Imagine his using these old stones just to build a nonsensical tower! Why did not he restore the old house? He had no sense of proportion.' But from the top of that tower the man had been able to look out upon the sea.6

Acknowledgement

An earlier and very different version of this post was circulated among some of my friends. Truly, I am grateful to these readers for their silences and niggardly comments, which convinced me to abandon that version and start again from scratch. The present post was not sent to these readers, and I am not going to thank them by name, though I should. Instead, I wish to acknowledge the absolutely vital contribution of Sharon Saar-Belodubrovsky, whose mixtures of Bach Flower Remedies I deem responsible for the image Fusion. A vision of the present post came to me as Sharon gave me a reflexology treatment.

Works Cited

- Ludwig Wittgenstein, Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus, trans. C. K. Ogden (London: Kegan Paul, 1922), Proposition 6.54. The quotation is the original German (also in this volume) of the part of Ogden's translation in parenthesis: 'My propositions are elucidatory in this way: he who understands me finally recognizes them as senseless, when he has climbed out through them, on them, over them. (He must so to speak throw away the ladder, after he has climbed up on it.)'

- The Monsters and the Critics, and Other Essays, "Beowulf: The Monsters and the Critics," 8.

- History of Middle-earth, Volume V: The Lost Road and Other Writings, The Fall of Númenor, "The second version of The Fall of Númenor," §14.

- Note that my account of the Númenor story of early 1936 is a rational reconstruction. The proper name of Elendil only appears in the second version, and here only as a chieftain of Beleriand and not as an exile of Númenor. But he appears as a man of Númenor in the unfinished novel of time travel begun in conjunction with the myth—indeed, he is introduced as if descending an invisible stair into the twentieth century! I infer that the time-travel story was commenced after the second version, with the story of Elendil only settling into the form that we know today as the time-travel story was commenced.

- The Monsters and the Critics, and Other Essays, "On Fairy-stories," "Recovery, Escape, Consolation," 153.

- The Monsters and the Critics, and Other Essays, "Beowulf: The Monsters and the Critics," 7-8.

While I sometimes lose track....

....of the meanings of the levels and views (or what can be seen from the various windows), I do enjoy thinking about the concepts you set out, and the line below really resonates:

:)

Thank you, wisteria. I saw your comment when you posted three weeks ago but my head was already full of the October post - which I guess will be even more difficult to follow. One thing with this series is that when I started I did not yet see the whole picture, and these summer posts on the Anglo-Saxon tower are attempts to articulate an understanding that I have only arrived at in the last half year. In my experience I always need two tries - a first time that explains to myself what I am thinking, and a second that explains to other people. What you have here is the first try. Hower, hopefully, in the New Year I will continue the series with a return to Lord of the Rings (I need a break before that). Then this post will come into its own because the spiral staircase, while a mere curiousity in relation to 'Beowulf: the Monsters and the Critics', becomes a major illumination of the Rings of Power. Simply put, the spiral is a descent in Time while the Rings of Power hold back time, and so the spiral loses its vertical axis and becomes merely a ring. But this must all wait a few months because my brain seriously needs a rest!