Túrin by firstamazon

Posted on 5 August 2022; updated on 5 August 2022

This article is part of the newsletter column Character of the Month.

Part One

Túrin is perhaps one of Tolkien’s most tragic characters. Based on a myriad of medieval tales from across Europe, such as the Greek myth of Oedipus, Sigurd from the Norse Volsung saga, and the Finnish story of Kullervo from the Kalevala,1 one of the main motifs surrounding Túrin’s story is grief—a recurrent theme in The Silmarillion. Such is the burden of Túrin’s fate that it is called by the professor the Tale of Sorrow.2

And while Sigurd has exercised a larger influence in the whole of the legendarium, Kullervo —as it was published by Verlyn Flieger in 2016—is appointed as the direct source for Túrin’s tale. In Flieger’s own words:

The hapless orphan, the unknown sister, the heirloom knife, the broken family and its psychological results, the forbidden love between lonely young people, the despair and self-destruction on the point of a sword, all transfer into ‘The Tale of the Children of Húrin’, not direct from Kalevala but filtered through The Story of Kullervo.3

All of these figures share with Túrin tragic fates in which some sort of doom looms over the course of their lives. In Túrin’s case, it was his father, Húrin, whose entire family was cursed by Morgoth himself when he was taken captive into Angband.

But back to where it all began: Dor-lómin, where Túrin was born. First child of Húrin Thalion and Morwen Eledhwen, Túrin was born in the same year in which Beren and Lúthien met in Doriath.4 Dark-haired and circumspect even as a child—traits he inherited from his mother—Túrin always seemed older than his years. As the Professor himself would describe him:

Túrin was slow to forget injustice or mockery; but the fire of his father was also in him, and he could be sudden and fierce. Yet he was quick to pity, and the hurts or sadness of living things might move him to tears; and he was like his father in this also, for Morwen was stern with others as with herself.5

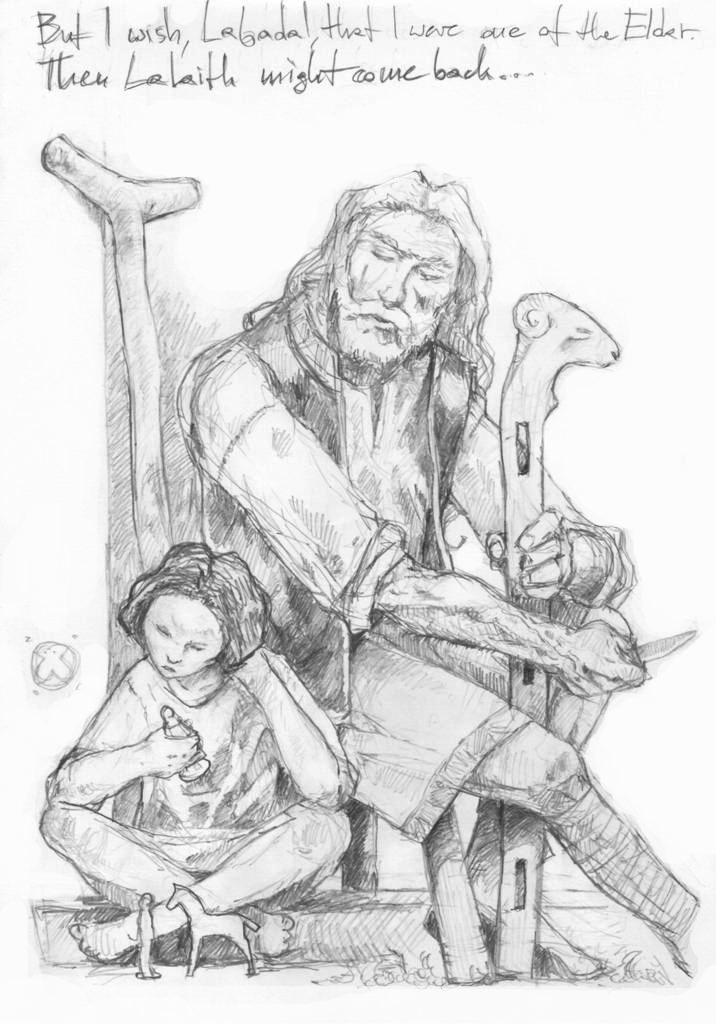

His childhood was spent mostly in loneliness until the birth of his little sister, Urwen, or Lalaith, whom he loved very dearly—even though it is said he was loved less for it.6 When the Evil Breath was released upon Dor-lómin, the plague claimed Lalaith’s life, and Túrin, only five years old,7 wept bitterly for laughter had died with her.

The boy turned, then, to the only friend he had, a man of his father’s household with a disabled leg named Sador, whom Túrin affectionately called Labadal because of his condition. Túrin helped the man with his woodwork, and Sador would sculpt little figures for him and tell tales of his youth during the Dagor Bragollach.

When Túrin was eight years old,8 in the month of Gwaeron9 (Q. Súlimë, the equivalent of March), his father Húrin presented him with his first weapon, an Elven-made dagger, which Túrin gifted, in turn, to Sador out of the pity of his heart. After that, Húrin left to fight beside King Fingon at the Union of Maedhros in the month of Lothron10 (Q. Lótessë; May) at what later would be called the Nirnaeth Arnoediad. By that time, Morwen was pregnant once more.

After that disastrous battle, the House of Hador was either destroyed or scattered, and no news11 reached Dor-lómin. Despite Húrin’s previous doubts about Elu Thingol and his reluctance to join the fray against the Enemy, Morwen had thought about sending Túrin to Doriath, where she assumed the House of Bëor would be well-received since, through Beren, she became kin to the king himself,12 as Bregor was both Beren and Morwen’s grandfather.

It was also during that period that the Easterlings crossed the Mountains of Mithrim and enslaved what remained of the House of Hador in Hithlum, but none dared approach Morwen’s house. She kept Túrin hidden inside, even as spies lurked around.

As the Easterling Brodda seized goods from Húrin's homeland and enslaved the people of Hador, Morwen, fearing that that would be Túrin's fate, decided to send him away with two faithful servants, Gethron and Grithnir (Halog and Gumlin in early versions13 of the tale). The birth of her new child was upon her, and that is the reason why she didn’t accompany Túrin and also why the boy never met his unborn sister, Nienor. Túrin grieved but, at last, agreed to leave, hung upon her promise to follow if she could.14 Thus it was that Morwen’s decision to stay behind was the first thread woven into Túrin’s fate. Leaving his mother behind was the first of his sorrows.15

The road was hard and filled with torments. Túrin and his companions suffered from thirst, hunger, and fear of the raiding Orcs. Without bread or water, they were lost in the mazes of Doriath16 before they were found by Beleg Cúthalion, one of the Doriathrim marchwardens that patrolled the forest’s borders. The hunter took them before the queen and king and, because of his regard for Túrin and esteem for Beren, Thingol accepted Túrin into his realm and considered him his foster-son.17

Of the servants that went with him, Gethron passed away of old age and the other, Grithnir, was sent back to Dor-lómin with an escort, bringing gifts and word of Túrin’s well-being to Morwen, who refused Melian’s plea to join them in Doriath. She wouldn’t leave out of pride and because Nienor was still an unweaned infant. When Túrin learned of this, he fled into the woods and wept—and this was the second sorrow of his life.

In turn, the messengers brought back the Helm of Hador, a powerful heirloom carved with a figure on its crest depicting Glaurung, made by the great dwarf-smith Telchar of Nogrod18 or Belegost19 (depending on the source), and which was capable of guarding those who wore it from arrow wounds and even death.20The Unfinished Tales says that the helm passed from hand to hand as a gift, first from Azhagâl, Lord of Belegost, to Maedhros, son of Fëanor; then, from Maedhros to his cousin Fingon the Valiant who, unable to find a head and shoulders that could fit the helm, decided to pass it on to the only ones who could wear it: Hador, and later his son, Galdor.21 Thingol kept the Dragon-helm for safekeeping while Túrin was still a child.

Once in Doriath, Melian watched over Túrin, but the boy often spent his time in the woods in the company of an Elf-maiden named Nellas. Unmentioned in the published Silmarillion, Nellas was responsible for teaching Túrin the Sindarin tongue, as well as “the ways and the wild things of Doriath.”22 As he grew up, Túrin became increasingly concerned with the deeds of Men and stopped calling for Nellas—even though she would still watch over him from afar.

Túrin spent nine years in Doriath—that is, until he turned seventeen. Thingol and Morwen often exchanged messages and news, and Túrin learned that his mother fared well and his sister grew in beauty. He himself became very tall, taller even than the Elves of Doriath, and he was a strong but quiet person, hard to make friends with because of his seriousness. By this time, Beleg used to take him to the forest to teach him archery and swordsmanship, and they developed a deep bond.

Thingol kept sending messengers to Dor-lómin until, one day, none returned, and he said he would send no more. Túrin grieved the news for a few days and decided to leave Menegroth with the king’s leave. He asked Thingol for weapons, which were granted to him, and reclaimed the Dragon-helm of his forefathers.

Túrin said his intention was to go in search of his family, but Thingol warned him that he would send no escorts to accompany him. Then, the king advised Túrin to test his strength and grow fully into his manhood before attempting the road north, and this counsel Túrin heeded. He went to the northern marches of Doriath, and there, beside Beleg Strongbow,23 who was his greatest friend and the only one who surpassed him in valor,24 Túrin fought against the servants of the Enemy. And despite his young age, he was brave and bold, and word of his fame ran far across the forests of Doriath.

It is when Túrin was twenty years old, returning from the fray in the forests, that one incident involving one of Thingol’s lords finally drove Túrin into his doom. This lord was Saeros—Orgof, on the oldest version of the tale—son of Ithilbor and one of the Nandor,25 an elder Elf of great prestige in the king’s court who envied Túrin’s position as foster-son.

The story of the enmity between Túrin and Saeros changed throughout the evolution of the legendarium. In the Lay of the Children of Húrin, Orgof offered him a golden comb so Túrin could fix his appearance,26 while in The Silmarillion,27 Túrin’s only incitement was to look unkempt, unfit for Thingol’s halls. However, in The Children of Húrin and The Unfinished Tales, not only his appearance was aggravating, but Túrin, weary and distracted, sat at the table with the other elders at Saeros’ place.28

The outcome is the same, though. The Elf lord, who insulted Túrin and his kin (the women, to be more exact), received a goblet in the face for it. In the Lay, Orgof dies on the spot, shocking the whole court—the king included—though in later versions he is only gravely injured.

In these two versions, Mablung held Saeros responsible for what came to pass, saying that if either sought to take revenge upon the other, evil deeds would befall those in Doriath. And the foresight did indeed come to pass, as Saeros ambushed Túrin in the woods the next day and tried to kill him, receiving an injury on his sword arm. Túrin, overtaken by wrath, stripped Saeros of all his clothing and ran after him like a hound,29 leading him to jump to his death on the Esgalduin.

Mablung ran after Túrin and tried to stop him, not knowing Saeros had offered first offense. When the deed was done, he asked Túrin to go back to Menegroth with him, so he could hear Thingol’s judgment. But Túrin, fearing being taken prisoner, refused Thingol’s law and judgment, choosing the life of an outcast instead. Mablung took the word about what happened to the king, and after hearing what he had seen—that is, Túrin chasing Saeros to his death—Thingol chose to forgive Túrin if he would accept it but banished him from Doriath unless Túrin would beg for the king’s forgiveness.

Then Beleg, arriving late at the council, brought forth Nellas from the woods, who retold the tale of how Saeros assaulted Túrin first. Thingol then changed his sentence and told the council that, instead of waiting for Túrin’s forgiveness, he would send someone with the word of his pardon. Beleg volunteered to find his friend, whom he loved,30 and asked for a sword of worth. Thingol bade him take any from his armories save his own, and fate deemed that Beleg chose Anglachel, twin blade of Anguirel, both made by Eöl of Nan Elmoth. Melian predicted that the sword still held its master’s malice,31 but Beleg took it anyway.

Believing himself an outlaw, Túrin didn’t return to the northern marches he and Beleg used to guard, instead turning south. There Haleth’s folk used to dwell but at the time of Túrin’s tale it was a region that lived under the fear of Orcs and outlaws,32 and there were many who robbed and were cruel. These outlaws were also called Gaurwaith, the wolf-men, and they wandered the western marches of Doriath and were hated almost as much as the Orcs.

Many of these Men came from Dor-lómin, such as Andróg—who was being hunted for the murderer of a woman in his land—but also the old Algund and Forweg, who was their captain. They tracked Túrin down, and when Túrin came out into a glade, he found himself within a circle of armed men with bent bows and drawn swords.33 Túrin dared them to fight him, alleging many would be dead by his side at the attempt. At that, one of the outlaws shot an arrow aiming at Túrin’s face, but he leapt aside and threw a rock at the man, breaking his skull. Túrin asked to join the band in the dead man’s stead.

Even though Forweg would take him, Túrin was not easily accepted, though, and one of the outlaws—Ulrad, a friend of the fallen man—complained this was not the way to gain passage into a fellowship. So Túrin offered to fight those who were willing, and Andróg would have, but admitted Túrin was their better. They asked him their name, and Túrin replied it was Neithan, the Wronged, and thus he was known to these people, who took him as one of their own. This was the first time Túrin changed his name—but not the last.

When asked why he became an outlaw, Túrin claimed he had suffered injustice, but he didn’t reveal his true identity to anyone, nor where he had come from. The outlaws respected him for his bravery and skills in the woods, but they also feared his anger,34 which sometimes was unpredictable. Unable or unwilling to return to either of his homes, Dor-lómin or Doriath, or seek refuge elsewhere, Túrin stayed with the outlaws until the next Spring, neither reprimanding nor stopping their evil deeds, and enduring the hardships of his new life.

The outlaws would not dare approach the homesteads of the Men in the woods of Teiglin because of the danger of being hunted down. Thus it was that, one day, Túrin noticed the absence of Forweg and Andróg, his friend,35 and taken aback by the poor state of their camp, went to the woods, thinking about the Glittering Caves. There he saw a young woman running in fear, her clothes rent by thorns, and she stumbled and fell to the ground before him.

Túrin leapt with his drawn sword and killed the man that came in pursuit, only later realizing it was his captain, Forweg. Andróg came right behind, and called it an evil deed even for an outlaw, for they had needs of their own, and drew his sword in turn. Túrin’s anger was great, and he dared Andróg to either leave the woman alone or join Forweg in death. Andróg admitted he was no match to Túrin alone. As for the woman, she offered a recompense if Túrin took both Forweg and Andróg’s heads to her father, Larnach, but he refused, telling her to go back home.

When they returned to the camp, Túrin announced Forweg’s death and the manner of his dying, and bid Andróg to tell his version of the tale, which he did. Túrin urged the outlaws to either take him as their new leader or let him go, and if they wanted to kill him, they should try. Andróg, though, claimed they would forfeit their lives needlessly and lose Túrin, who was the best among them. So it was that Túrin was made their captain. Many, such as Algund, thought this was well done, and that Túrin in fact might lead them well, even take them back to Dor-lómin in the end.36

Though at this point Túrin even dared to hope in a small, free lordship for himself, he first took his band far from the homes of Men—the exact geography, though, is unclear, and in a note37 in The Unfinished Tales, Christopher Tolkien points out that it was likely in the Vales of Sirion and not far from their previous abode in the forests south of Teiglin.

Another note in the same book says that it was in this moment that Túrin claimed to have done justice with Forweg’s death because he was also from the House of Hador. Algund recognized, then, Túrin’s heritage and it became openly known that the one who led them was Túrin, son of Húrin Thalion.38 This version was later discarded in favor of Túrin’s secrecy for narrative purposes.

Meanwhile, Beleg looked in vain for Túrin, and the situation in Dimbar—where the Dragon-helm and the Strongbow were no longer seen—got worse; the servants of Morgoth grew in number and in boldness until it was overrun a year after Túrin had fled Doriath.39 Beleg’s path took him to the place where Túrin had rescued the daughter of Larnach, and there he heard of the deeds of a “tall and lordly Man, or an Elf-warrior.”40 Beleg followed their trail, even though Túrin was so well-learned in the crafts of the wood and field that the Elf was always some days behind them.

Túrin’s band became uneasy to know they were being followed and could not shake off their pursuer. Until, one day, Beleg knew of raiding Orcs that plundered and killed the villages of Men. The outlaws' scouts were aware too, and even if they didn’t care about the captives, they cared about the booty. Túrin advised them not to engage the Orcs, but the others didn’t want to hear his council. So giving the lead of the band to Andróg,41 he and Orleg went to spy upon the enemy. But they were discovered, and one Orc managed to raise the alarm.

Orleg and Túrin fled, and the first was shot down by an arrow—Túrin only escaped because of his Elven-mail and eluded the pursuing Orcs, wandering into lands he didn’t know. The other outlaws, still waiting for Orleg and Túrin’s return, grew restless. Andróg told them to wait for their captain, and it was in the middle of their debate that Beleg appeared, startling them all. Afraid of his presence and thinking him a spy of Thingol, they tied him to a tree, questioned him, and treated him cruelly.42

Andróg coveted Beleg’s bow and wanted to slay him, but Algund was against it.43 Beleg would only speak to Túrin, and so the outlaws let him tied to the tree without food or water for two days. When still Túrin did not return, many became inclined to kill the Elf and move on. Their cruelty was such that Ulrad had a brand from the fire they had lit, ready to imprint upon Beleg’s flesh, but it was in that moment that Túrin returned. Seeing the Elf’s haggard face, he wept with joy and ran to free his companion. Thus, Beleg and Túrin renewed their friendship.44

Túrin at once felt grieved for having let his band get away with the murder of other Men, realizing the same could have happened to his only and dearest friend. Túrin took care of Beleg’s injuries and called out his fellow outlaws, claiming they had acted as Orcs. So Túrin bade them to swear an oath to only harm the servants of Angband, sparing Elves and Men. Beleg then told Túrin that he had been pardoned by Thingol thanks to Nellas, but Túrin was not happy to hear those words—he didn’t even remember who the Elf-maiden was.45

Though Beleg urged his friend to return to Doriath and hold his helm high once more,46 Túrin’s pride was still injured, and he would not suffer pity or pardon like a wayward boy, but wander the lands as a free man. He told Beleg he would not part from the outlaws if his band still wanted him as their leader, and Beleg tried to caution Túrin about the evil of some of them—Andróg most of all, who had handled him with more cruelty.

But Beleg’s plea was to no avail,47 and Túrin refused to leave, asking his friend to stay with him instead. So out of love, and ignoring the shadow he perceived lay before them, Beleg proposed they return to Dimbar where they were both needed. But to return there would mean to cut across through Doriath, and that Túrin would not do. Beleg was saddened by his friend’s stubbornness, and decided he would return to Dimbar nevertheless. Túrin, then, told Beleg to look for him on Amon Rhûd. Thus, they parted on what both thought it would be their last farewell.

Beleg returned to Menegroth to report to the king and queen, and Melian gifted him with a store of lembas—as The Children of Húrin reminds us, “the giving of this food belonged to the Queen alone”48—to be shared with whomever Beleg wished, and in this she showed Túrin the highest of favors, for never before had the Elves allowed Men to share their travel bread, and that would rarely happen again.

In The Silmarillion, it is then that Beleg asks for a sword and takes Anglachel for his keeping. Regardless of when, Beleg returned to the northern marches in all versions, even though he would not stay there throughout the winter and, out of the love in his heart, would seek Túrin out once more.

Túrin’s tale is a great example of what Tolkien called the “dyscatastrophe”,49 or the sorrow and failure after a (mostly unexpected) negative turn of events—opposed to the happy endings of the eucatastrophe—as we will see on the next part of his biography, when we will recount the outlaws’ path to the Amon Rhûd and their meeting with the dwarf Mîm. Suffice to say that Túrin was already famed in the lands around Doriath, and that the doom laid upon his house by Morgoth would soon reach him.

Works Cited

- Letters of J.R.R. Tolkien, "131 To Milton Waldman."

- The Silmarillion, "Of Túrin Turambar."

- The Story of Kullervo.

- The Children of Húrin, "The Childhood of Túrin."

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Unfinished Tales, Narn i Hîn Húrin, "The Childhood of Túrin."

- The Children of Húrin, "The Childhood of Túrin."

- Unfinished Tales, Narn i Hîn Húrin, "The Childhood of Túrin."

- The Children of Húrin, "The Childhood of Túrin."

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- The History of Middle-earth, Volume III: The Lays of Beleriand, "The Lay of the Children of Húrin."

- Unfinished Tales, Narn i Hîn Húrin, "The Departure of Túrin."

- The Children of Húrin, "The Childhood of Túrin."

- The History of Middle-earth, Volume III: The Lays of Beleriand, "The Lay of the Children of Húrin."

- The Children of Húrin, "Túrin in Doriath."

- Ibid.

- The History of Middle-earth, Volume IV: The Shaping of Middle-Earth, The Quenta, §11.

- Unfinished Tales, Narn i Hîn Húrin, "The Departure of Túrin."

- Ibid.

- Ibid.; The Children of Húrin, "Túrin in Doriath."

- The Children of Húrin, "Túrin in Doriath."

- Unfinished Tales, Narn i Hîn Húrin, "Túrin in Doriath."

- Ibid.

- The History of Middle-earth, Volume III: The Lays of Beleriand, "The Lay of the Children of Húrin."

- The Silmarillion, "Of Túrin Turambar."

- The Children of Húrin, "Túrin in Doriath"; Unfinished Tales, Narn i Hîn Húrin, "Túrin in Doriath."

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- The Children of Húrin, "Túrin in Doriath."

- The Children of Húrin, "Túrin Among the Outlaws."

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Unfinished Tales, Narn i Hîn Húrin, "Túrin among the Outlaws," note 11.

- Ibid., note 10.

- The Children of Húrin, "Túrin Among the Outlaws."

- Ibid.

- Unfinished Tales, Narn i Hîn Húrin, "Túrin among the Outlaws."

- The Silmarillion, "Of Túrin Turambar."

- The Children of Húrin, "Túrin Among the Outlaws."

- The Silmarillion, "Of Túrin Turambar."

- The Children of Húrin, "Túrin Among the Outlaws."

- Ibid.

- The rest of this conversation—Beleg returning to Menegroth and the gift or gifts made by Melian—does not appear in the Unfinished Tales version.

- The Children of Húrin, "Túrin Among the Outlaws."

- "On Fairy-Stories," "Recovery, Escape, Consolation."

Well done!

Thanks for this clearly-written bio! Túrin's story and everything that went into it is no easy task. Looking forward to the next part(s)!

Also did not know about dyscatastrophe... Like a catastrophe but worse. Yes, sounds like Túrin.

Thank you! Ah, yes, the…

Thank you! Ah, yes, the dyscatastophe is a concept that entangles so many things - and it can frankly be used in many other characters of the Silm, right? Thank you for this comment, and for bearing with me! <3

Doomed Túrin's journey begins

It is so helpful to read the outlines of all the different versions of the first part of his tale collated clearly like this. It is easy to forget the little details when caught up with the narrative flow when reading.

Túrin's storis is one of…

Túrin's storis is one of those that has so many versions it really is very difficult to remember which information came from where - I'm glad this bio is useful in that way! Thank you for the comment!

Well done for tackling this…

Well done for tackling this very complex bio!

It is so important and such a tangle of misfortune and error...

How much Turin has lost already, by the time of what is called "first sorrow"!

It has been an interesting…

It has been an interesting challenge to find all the different versions of Túrin, the little bits and pieces left behind as the story progressed - and one realises just how much tragedy this character has gone through his whole life. Thank you for the comment!

Túrin's story is what pulled…

Túrin's story is what pulled me back into the active online fandom and poor sad dumpster fire Boy will always have a very large place in my heart.

You've done such an amazing job in summarizing the various versions of his story and drawing together the threads of his early life. ?

Aahh sorry for such a late…

Aahh sorry for such a late reply! Thank you so much for reading and commenting! Turin has been my favorite character for a very long time, so this was a bit intimidating to write - but I'm happy to know it was effective! ?