The Fall of Gondolin Reflected in History by MirienSilowende

Posted on 21 January 2023; updated on 10 February 2023

This article is part of the newsletter column A Sense of History.

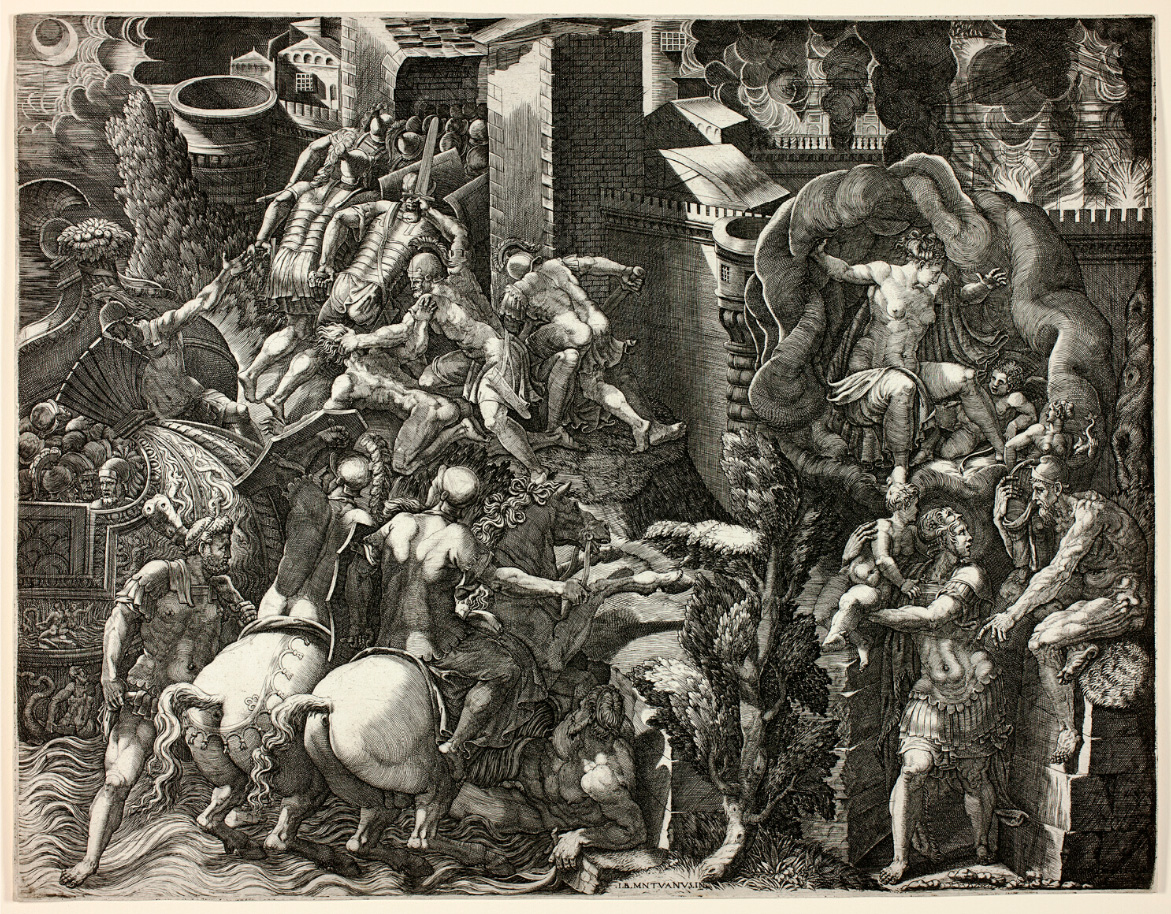

This article aims to look at the events in Gondolin when Melkor destroyed the city and compare that tragedy to similar sacks in history and classical literature.

Glory dwelt in that city of Gondolin … and its ruin was the most dread of all the sacks of cities upon the face of Earth. Nor Bablon, nor Ninwi, nor the towers of Trui, nor all the many takings of Rûm that is greatest among Men, saw such terror as fell that day ….1

Gondolin was the home of the Twelve Houses, the one that was chosen by Ulmo, the city that Ulmo desperately tried to save. Tolkien referred to it as the most dread of all the sacks of cities, referencing literary Homeric cities and cities within our known history: Nineveh, the centre of the Assyrian Empire; Babylon and Rum; the so-often-taken Constantinople. This article aims to look at the Fall of Gondolin, and what happened there, and then to compare that with the aforementioned cities of Babylon, Troy, Nineveh, and Constantinople.

Gondolin fell in FA 510, after the Midsummer festival The Gates of Summer. One by one, the Houses fell, as did each Gate, and one by one, the great names of the Houses of Gondolin were slain:

Of the deeds of desperate valour there done, by the chieftains of the noble houses and their warriors, and not least by Tuor, is much told in The Fall of Gondolin; of the death of Rog without the walls; and of the battle of Ecthelion of the Fountain with Gothmog lord of Balrogs in the very Square of the King, where each slew the other; and of the defence of the Tower of Turgon by the men of his house-hold, until the tower was overthrown; and mighty was its fall and the fall of Turgon in its ruin.2

First came the North Gate, where Gothmog led the charge with Balrogs and dragons. First Duilin and Penlod were slain. Then Rog and his House were slain, after making a valiant attempt to hold back the Balrogs with Galdor of the Tree. Slowly, the rest of the Houses were driven back to the Square of the King. The men of the Harp, without a leader after the treachery of Salgant, rescued Glorfindel and the House of the Flower, but perished in the attempt.

Gothmog came and Ecthelion battled him, losing his own life in the process. Turgon asked his people to follow Tuor, who had devised a secret escape route. He managed to lead out the survivors of Gondolin, of the houses of the Wing and the Tree. Of all that lived in Gondolin, less than a thousand survived the initial Fall:

Of those who went with Tuor and witnessed the fall of Glorfindel, it later says they were "nigh eight hundred," and of those who came out of Nan-Tathren in later years, there were "but three-hundred," and those who were described to have survived the Fall of Gondolin, including those who perished at Bad Uthwen, were described as a "sad remnant."3

Nobody would argue that the Fall of Gondolin was total, a tragic defeat with the loss of thousands of legendary warriors, considering that the army issued to the Nirnaeth was ten thousand strong. What about the other tragedies that Tolkien mentioned in the Fall of Gondolin? If they were less dread, were they then less tragic?

Babylon was conquered by the Persian Empire in 539 BCE. Cyrus, King of Persia, invaded Babylonia, the area around the city of Babylon in Mesopotamia, and then took the city. Some say that it was an acquisition without battle; others say the city was besieged. Interestingly, there are accounts that Babylon was taken on the night of an important feast to celebrate the Spring Festival. It appears that the city was taken quickly, the Gates to the West and East falling, and without great bloodshed.4

Nineveh, the centre of the Assyrian Empire, fell to the King of Babylonia in 612 BCE. It was the largest city in the world at the time and became known as one of the most shocking events in ancient history. The army, which was made up of forces from the Medes and Babylonian kingdoms, invaded Nineveh in May. The city fell in July. The soldiers continued to loot the city until August when the soldiers returned home.

There are writings by the Jewish prophet Nahum about the fall:

An attacker advances against you, Nineveh. [...]

The shields of his soldiers are red;

the warriors are clad in scarlet.

The metal on the chariots flashes

on the day they are made ready;

the spears of pine are brandished.

The chariots storm through the streets,

rushing back and forth through the squares.

They look like flaming torches;

they dart about like lightning.

He summons his picked troops,

yet they stumble on their way.

They dash to the city wall;

the protective shield is put in place.

The river gates are thrown open

and the palace collapses.

It is decreed that the city

be exiled and carried away.5

Troy is a story lodged in literary history, taken from The Iliad. But this too was a historical event, of which Homer wrote so long ago. Troy was a city in what is now western Turkey, and was at its height at the end of the Bronze Age. Archaeologists have found that there was indeed a sack of the city in 1200 BCE, but beyond that it is hard to say. Returning to The Iliad, there was war between the Greeks and the Trojans because Helen was taken from Sparta by the Trojans, causing great hostilities. Like the Fall of Gondolin, The Iliad has many great names that have survived in history—Achilles, Hector, Odysseus, Ajax, Aenas, and Diomedes.

There was a ten-year war, with the armies decimated on both sides. The victory in the end was total, when the Greeks managed to infiltrate the city thanks to a great horse that they built and stowed warriors into, appearing to give up on the siege and leave. Once within the city, they killed every man and boy and took the women and girls captive. Only a small band of refugees, including Aeneas, the son of King Priam’s cousin, escaped.

There are similarities in the fall of Troy and of Gondolin. The people of Troy feasted, believing their foes to be gone, unknowing that they were already among them:

So feasted they through Troy, and in their midst

Loud pealed the flutes and pipes: on every hand

Were song and dance, laughter and cries confused

Of banqueters beside the meats and wine.

They, lifting in their hands the beakers brimmed,

Recklessly drank, till heavy of brain they grew,

Till rolled their fluctuant eyes.6

And just like in Gondolin, the massacre was total:

So through the city of Priam Danaans slew<

One after other in that last fight of all.

No Trojan there was woundless, all men’s limbs

With blood in torrents spilt were darkly dashed.7

Finally, we look at Constantinople. This was much later in history, around 1453 CE. Constantinople was besieged by Ottomans for fifty-five days, a long time when being actively bombarded by cannon from land and sea. Constantinople, like Gondolin, was considered to be formidable, perhaps even impenetrable.8

But when the Ottomans invaded, they were grossly outnumbered. On May 29, the city was taken, and there was much looting and destruction of the Orthodox churches. As this was a city that was strategically important, it would be likely that the city itself, the infrastructure and buildings, would not be damaged.

When we look at history and the destruction of cities, we have to take into account the looting that takes place after the city falls. Victorious soldiers destroyed businesses, enslaved women and children, and took valuables from churches and wealthy households. This was the spoils of war and was condoned by the commanders, the leaders of the armies. The tragedy lies not just in the death of warriors in the siege and fall, but in the enslavement of the people who could not fight, the women and children.

This is mentioned by Quintus in The Fall of Troy, when the soldiers who had destroyed the city made sacrifices, enslaved the women, and killed the remainder of the royal family. The men were killed, but the women faced a more horrifying fate:

With anguished hearts the captive maids looked back

On Ilium, and with sobs and moans they wailed,

Striving to hide their grief from Argive eyes.

Clasping their knees some sat; in misery some

Veiled with their hands their faces; others nursed

Young children in their arms: those innocents

Not yet bewailed their day of bondage, nor

Their country’s ruin …9

We know that this was the case also in Gondolin. Many of the House of Hammer of Wrath were former thralls, and it has been suggested by some that Rog was named in captivity and chose to keep that name—Rog meaning demon.

In older days they had been much recruited by Noldor who escaped from the mines of Melko, and the hatred of this house for the works of that evil one and the Balrogs his demons was exceeding great.10

We know nothing of what happened to the people who did not manage to flee in the Secret Way with Glorfindel and the others. Did Melkor and his people destroy everyone? Did they take the weaker ones to the mines to be enslaved? It is likely that the Orcs looted, and Melkor did not need to keep the city intact to keep for his own use. Their spoils would indeed have been great. When Tolkien referred to the Fall as the most dread, it could be that he was referring to the aftermath, the slow march of women and children leaving their home, facing torment in the mines. He could have been pondering the murderous rage of Melkor’s forces as they razed a city to the ground. He could have been considering the sheer scale of lives lost. But certainly it was a tragic chapter in an already dark age.

Works Cited

- The History of Middle-earth, Volume II: The Book of Lost Tales 2, The Fall of Gondolin, "Tuor and the Exiles of Gondolin."

- The History of Middle-earth, Volume IV: The Shaping of Middle-earth, The Quenta, §16.

- The History of Middle-earth, Volume II: The Book of Lost Tales 2, The Fall of Gondolin, "Tuor and the Exiles of Gondolin."

- Xenophon, Cyropaedia.

- "ABC 3 (Fall of Nineveh Chronicle)." Livius, July 11, 2020, accessed January 21, 2023.

- Quintus Smyrnaeus, The Fall of Troy.

- Ibid.

- Myles Hudson, "Fall of Constantinople," Britannica, August 29, 2012, accessed January 21, 2023.

- Quintus Smyrnaeus, The Fall of Troy.

- The History of Middle-earth, Volume II: The Book of Lost Tales 2, The Fall of Gondolin, "Tuor and the Exiles of Gondolin."

Very interesting, both the…

Very interesting, both the expansion of the comparison with those cities and your choice of quotations, and also your further thoughts on this!

Oh thanks very much! It was…

Oh thanks very much! It was an enjoyable subject to research, albeit dark!

Fantastic analysis and great…

Fantastic analysis and great selection of examples. Thank you for sharing

I really appreciate that! It…

I really appreciate that! It was nice to go back to Gondolin for a while. Thanks so much for reading!

Brutal

War is brutal, and reading about parallels between Gondolin and cities sacked historically reinforces that for me. It is interesting that Tolkien referenced those real world events as a comparison.

I must admit that I had failed to take into account the numbers of Gondolindrim who escaped with Tuor and Idril being only a small percentage of the population. So therefore there may well have been a much greater number of non-combatant elves who were either completely wiped out in the fighting, killed after the city was taken or who were possibly marched off to be enslaved.

That is absolutely true. War…

That is absolutely true. War is brutal! Tolkien focused on the attack and then the escape so it is logical that our thoughts follow his narrative. The alternative, thinking of the fate of these non-combatants, is hard to do.

This is both a great…

This is both a great analysis and helpful summary of the events of the fall of Gondolin, which I admit I am not that familiar with. I like that you chose to use the sacks of cities that Tolkien actually mentions in the FoG text (I kind of love how explicitly he connects his early stories with the real world). I never really think of things like the taking and enslavement of captives in the context of Tolkien's world, but this kind of literary-historical comparison helps expand what's in the stories. Truly horrific, but great inspiration for exploring some darker corners of the legends in fanworks.

Thank you for reading and…

Thank you for reading and commenting! As a rule I employ some level of assumption when doing these articles but with Tolkien being so explicit about these cities, it seemed appropriate.

As a reader of Tolkien I am with you, I do not think of the captivity and enslavement, although Tolkien specifically referenced the mines and the thralls that Melkor kept so we know this would have been the case. As historian it is something that stands out in technicolour.

I certainly hope that my writing provides inspiration. Thank you so much!

Hi Mirien. Thanks for this…

Hi Mirien. Thanks for this fascinating article! I had just recently reread The Fall of Gondolin in Lost Tales 2, and was struck again by all Tolkien's detail of what an utterly tragic catastrophe it was. I remember noting his comparison (with slightly different names) to real ancient sacks of cities and appreciated your bringing that out here. Also, appreciated your looking at what happened in those cities and comparing those details to what Tolkien says happened in Gondolin, especially the account of fall of Babylon the night of a spring festival, something I didn't know. It's clear Tolkien drew on the historical accounts. Thanks for your research and analysis. :-D

You are so welcome! I love…

You are so welcome! I love to link up the two, the book lore and history, and in this case we had some very distinct clues to work with. I am glad you enjoyed reading it!