Talking amongst Ourselves: Tolkien Fanfiction and Fanon by Dawn Walls-Thumma

Posted on 16 September 2023; updated on 6 October 2023

This article is part of the newsletter column Cultus Dispatches.

Back in March, I shared a set of data about canon, fanfiction, and authority under the title Who Gets to Say? Who gets, in other words, the right to make decisions about a text—whether a book, film, TV show, or something else entirely—and what it says, the characters who drive it, and the story it contains? The data came from the 2020 Tolkien Fanfiction Survey and, among several points considered, looked at a series of five items about whose "views on the canon" the participant considered when writing fanfiction. Most participants agreed that they "consider Tolkien's views on the canon" (68%), but I will admit that I was rather surprised by the second most considered of the five options: other fans. (The other three, in order from most to least agreement, were Tolkien scholars or experts, Christopher Tolkien, and Peter Jackson and other filmmakers.) 61% of participating authors considered other fans' views on the canon when writing fanfiction.

That's not far behind the consideration they give Tolkien himself (and the third most considered—Tolkien scholars and experts—received just 44% agreement). I did not expect this—though the more I think on it, the more I realize that maybe I should have.

Fandom—and fanworks in particular—are a conversation after all. They rarely occur in a vacuum. I remember the first fanfiction I wrote, before I even knew fanfiction was a thing, and how eager I was for my husband to read The Silmarillion so that he could read my story about The Silmarillion. In writing it, it was as though I'd been talking to myself but suddenly realized my words were going nowhere. I hankered for a conversation partner. We generally accept that our work is in conversation with the original text, but much of the time, our work is also in conversation with each other.

This month, as I wrap up a series of articles on Tolkien's canon, I'd like to consider those conversations, namely the concept of fanon: fan-generated ideas and theories that rise almost to the level of canon within a fan community. This article will use data from the Tolkien Fanfiction Survey, which I ran in 2015 and 2020, the latter in collaboration with Maria K. Alberto. The survey included writers and readers of Tolkien-based fanfiction. Most items offered five possible responses: Strongly Agree, Agree, Disagree, Strongly Disagree, or No Opinion/Not Sure. In the 2015 survey, there were 1,052 participants, 642 of whom were fanfiction authors, and in 2020 there were 746 participants, 496 of whom were authors. In this article, when I say "agree," I refer to fans who selected either Agree or Strongly Agree, unless otherwise specified (likewise for "disagree" and the relevant survey choices), and unless I state otherwise, both text and images refer to the data from the 2020 Tolkien Fanfiction Survey.

"Just Fanon"

Probably part of my surprise that, when writing fanfiction, 61% of authors "consider other fans' views on the canon" comes from the era of fandom of which I was a part. I began lurking in the Tolkien fandom in 2004 and participating actively in 2005, right on the heels of the Lord of the Rings film trilogy. I've written elsewhere about how the convergence of the films, growing home internet access, and Web 2.0 established Tolkien as one of the first online megafandoms, throwing together people who had been Tolkien fans for decades with newly minted film fans (like me). These interactions were sometimes tense. We (the new filmverse fans) had a lot of enthusiasm, not a lot of knowledge, and there were a lot of us. Furthermore, we were often learning about Tolkien through not-entirely-reliable online sources (including fanworks), and few of us yet had the skills to evaluate the credibility of what we were finding online. Misconceptions abounded! So did fanon.

In the fandom I encountered as a new fan, misconceptions and fanon were often equated. Fanon was not a complimentary term. "Oh that's not canon, it's just fanon" is something I remember hearing a lot. In the mid-2000s, the fanfiction author Tinni maintained a site called Canon? No! It's Fanon! for evaluating the various fanons she encountered, and how she defines both fanon and the purpose of her website both shed light on the attitude toward fanon at the time:

Fanon are inventions of fan fiction authors that for one reason or another appear to have taken the status of a canon within the Tolkien's fandom. I.e. it is believed that these ideas were put forward by Professor Tolkien himself, which of course is not the case.

. . .

The inspiration for this site came when I noticed that multiple authors were using the same fandom inventions. At first I paid it no mind but it soon became clear that some of these authors mistakenly believed that some of these fandom inventions were actually things that Tolkien himself suggested. This disturbed me, more so because I have read that Tolkien himself was opposed to groups of people imposing their views and interpretation of his world on others. As such the purpose of this site is only to identify fandom inventions that appear as though they are being adopted as the word of Tolkien. I will make every effort to withhold my personal views and keep my opinion from interfering, since I do not want to become a source of fanon myself. All I will do is provide you with information and direct you to the proper location so that you can make up your own mind.1

Several assumptions jump out here that were very much part of how I remember my experience in mid-2000s Tolkien fanworks fandom. First is authority. My series on canon really centered on authority: the initial question of "Who gets to say?" Here, that is unequivocally Tolkien. The idea that "fandom inventions" could coexist alongside "the word of Tolkien"—or even supplant them in a way that is intentional and thoughtful—is not considered. One-off ideas that happened to be on a piece of paper that Christopher Tolkien selected for publication are elevated to "quasi-canon" and considered superior to "interpretations and extrapolations made by fan fiction authors based on material written by Tolkien himself, [which] are still just fandom inventions" (emphasis mine).

This points to the trivialization of fanon in early online fandom, including the notion that fanon is synonymous with misconception, which is itself ironically a misconception. Tinni uses the rather strong word disturbed to describe her reaction to discovering that fans sometimes didn't know which details came from Tolkien and which came from other fans, reflecting an attitude that I found common at the time that a lack of knowledge about Tolkien's books was problematic and something that fans should be working to remedy. In fact, fanon doesn't have to be a misconception and doesn't have to be inferential either, and it certainly is not trivial. It can reflect years or decades of fannish discussion, distilled into a widely accepted fanon that signals awareness of the fannish (and, with it, canonical) context and agreement with a particular viewpoint. (Likewise, choosing to ignore or subvert a fanon carries its own message.)

I don't mean to pick on Tinni. Her website has been offline for more than a decade now, and when it was still up, it reflected the fandom culture of which she was part. I used it many times and found it both entertaining and a valuable research tool. She always was careful to state that her approaches were not universal and that she anticipated disagreement. It does, however, reflect a culture found in some early online Tolkien fan communities where fans "knew their place." They did not carry the same authority as Tolkien to work with the texts, and anything that was fan-derived was going to be suspect, coming not from Tolkien himself. The mass adoption of these ideas—fanon—was therefore a threat to Tolkien's authority.

Hence, I was surprised when I ran the 2020 Tolkien Fanfiction Survey data and found that, sometime in the last decade, that attitude had shifted. A lot. (Being part of the fandom still, I of course knew that, but seeing the "hard data" still managed to surprise me.) During that time, fans had managed to gain authority over the texts that put them just slightly below Tolkien. Events like the Fun with Fanon Fest and the ever-growing Silmarillion Headcanon Survey (which necessarily includes a lot of fanons among the options) further show curiosity and even celebration of fan-generated theories about Tolkien's world, consistent with the data.

Author Views on Fanon

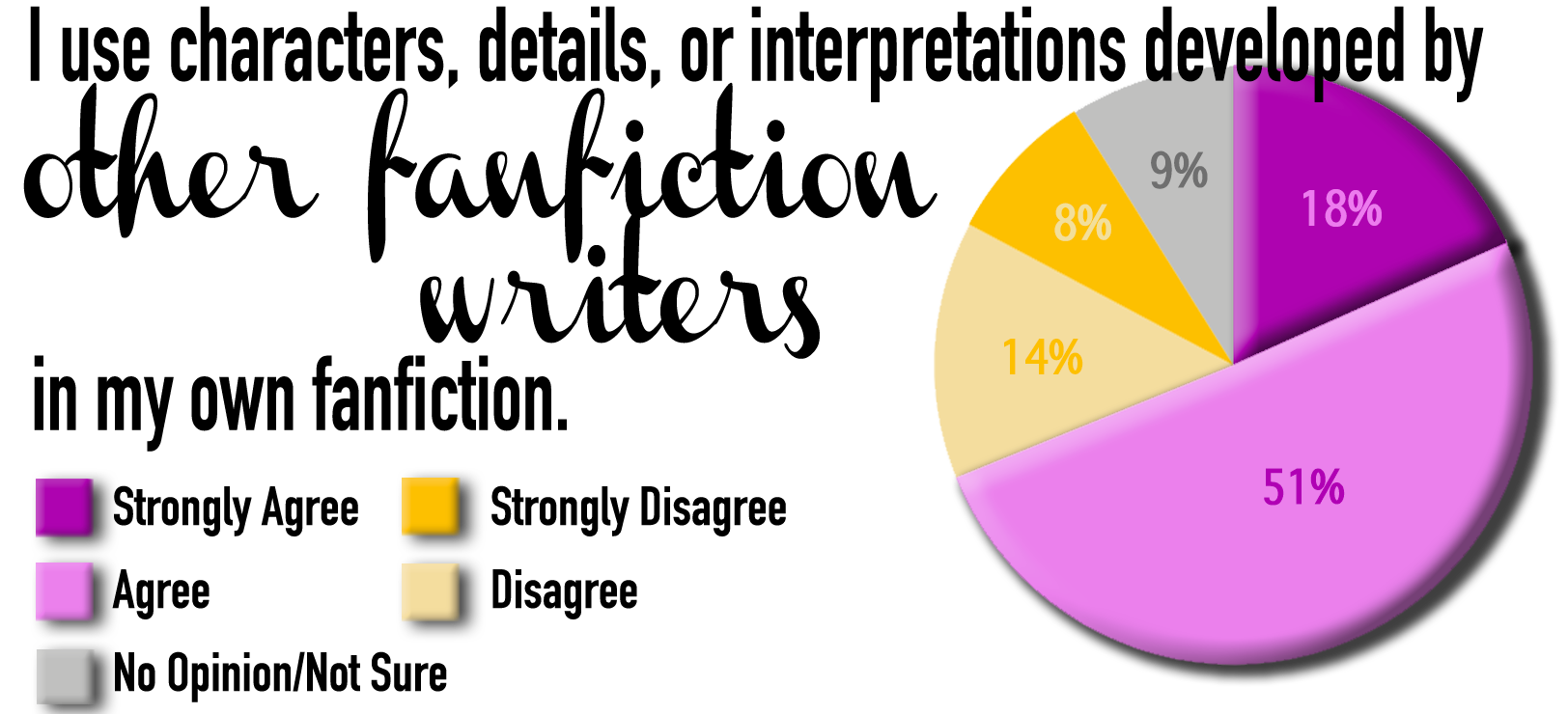

Does survey data suggest that authors are becoming more supportive of fan-generated ideas, including fanon, as the fandom matures? The short answer is: Yes, but it's complicated. The 2015 and 2020 surveys included two items that get at author attitudes toward fanon. The first is rather broad, encompassing all sorts of fan-generated ideas, inventions, and interpretations: "I use characters, details, or interpretations developed by other fanfiction writers in my own fanfiction." Here, the lack of change is itself notable. In both surveys, 69% of authors agreed with the statement, with 18% strongly agreeing and 51% agreeing. Since the data are almost unchanged between years, only the 2020 data is shown below.

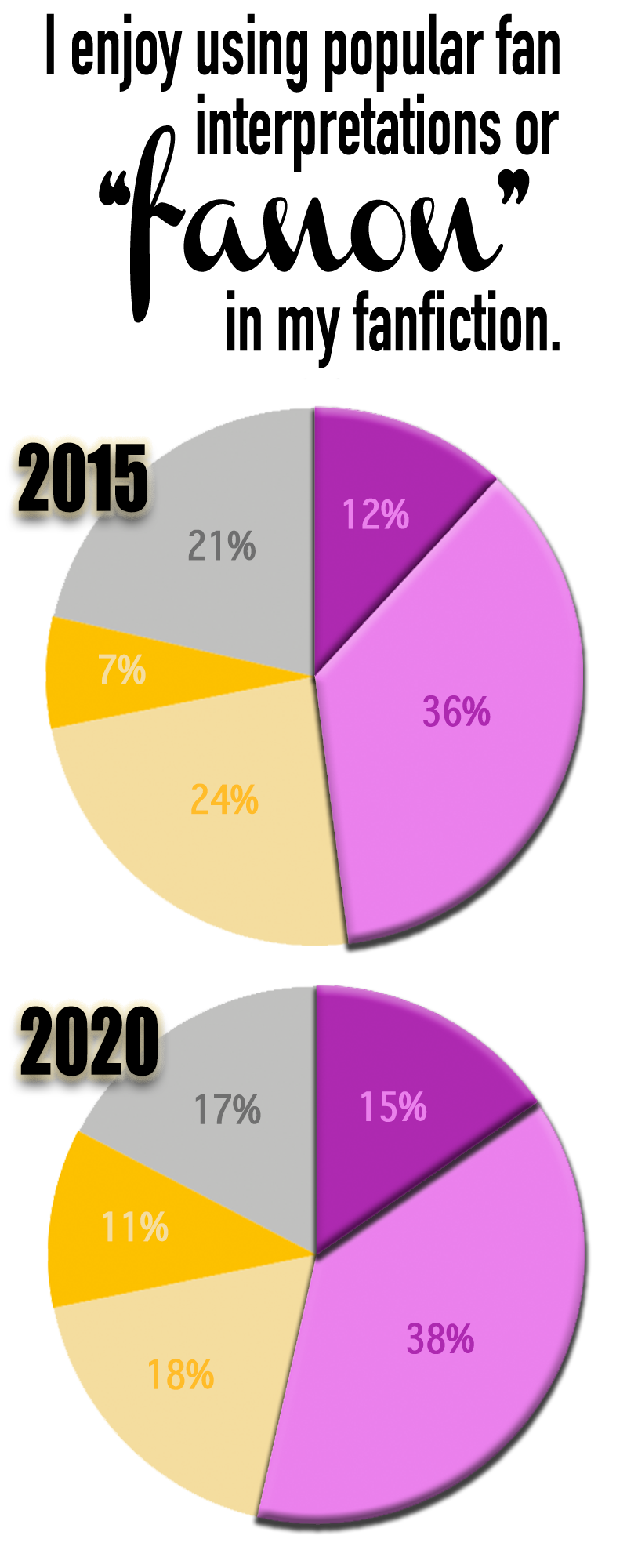

Another item asked specifically after fanon: "I enjoy using popular fan interpretations or 'fanon' in my fanfiction." Support for this statement drops off, with only 54% of authors agreeing in the 2020 survey. What caused the 15% difference? Perhaps it was the inclusion of the word popular. Just because someone utilizes another fan's "characters, details, or interpretations" does not mean that they are popular. As noted, the first statement casts a much wider net.

It is also possible that the word fanon itself is off-putting. As noted in the previous section, historically, in parts of the Tolkien fanworks fandom, fanon has not been viewed positively. Instead, it has been held as synonymous with a misconception, as shorthand for laziness, or indicative of a fan overstepping the bounds of authority.

Unlike the broader survey item discussed above, the survey data between 2015 and 2020 show some interesting shifts.

These data are rather complex and therefore interesting—and come always with the caveat that two sets of data do not a pattern make. First, there is an increase in 2020 of the number of fans who agreed with the statement, supporting my earlier perception that fanon is becoming more acceptable in the fandom. However, in 2020, there is also a shift toward either extreme. In 2015, the number of fans who Strongly Agreed or Strongly Disagreed was just 19%. In 2020, it had increased to 26%, with both the percentage of fans who Strongly Agreed and Strongly Disagreed increasing.

It is impossible for me to consider data from the 2015 survey without thinking of the impact of the Hobbit films, the final of which was theaters as the survey debuted. Media adaptations of Tolkien typically produce both news fans, who are less likely to have read many (or any!) of the books, and fanons generated by the films and film fandom, which often trigger a backlash from book fans who fear the corruption of Tolkien/Tolkien fandom by details found solely in or derived from an adaptation or simply grow weary of the constant presence of enthusiastic interest in versions of the story that they view as noncanonical. It is possible that the slightly lower support for fanon in 2015 comes from frustration with or worry about Hobbit film-based fanons, or perhaps it reflects the larger trajectory of accepting fanons and other fan-generated ideas.

The shift toward either extreme is harder to explain but may simply reflect a maturing fandom. As noted above, if a popular adaptation can be predicted to do one thing, it is to introduce new fans to Tolkien. In 2015, authors had been participating in fandom for a median of four years; in 2020, that median had increased to five years. This extra year of fandom experience for the average author may have provided the time needed to formulate stronger opinions on questions around fan authority and fanon.

Reader Views on Fanon

Something I have noticed across a couple datasets now is that readers often want to see more of something that authors are less interested in producing. (Interest in reading versus writing femslash comes immediately to mind.) Of course, this in no way obligates authors to meet this demand, and I do not want to imply that authors are somehow neglecting readers or, in related debates around comments and feedback, deserving of less feedback on their work. However, the attitudinal differences are interesting to contemplate.

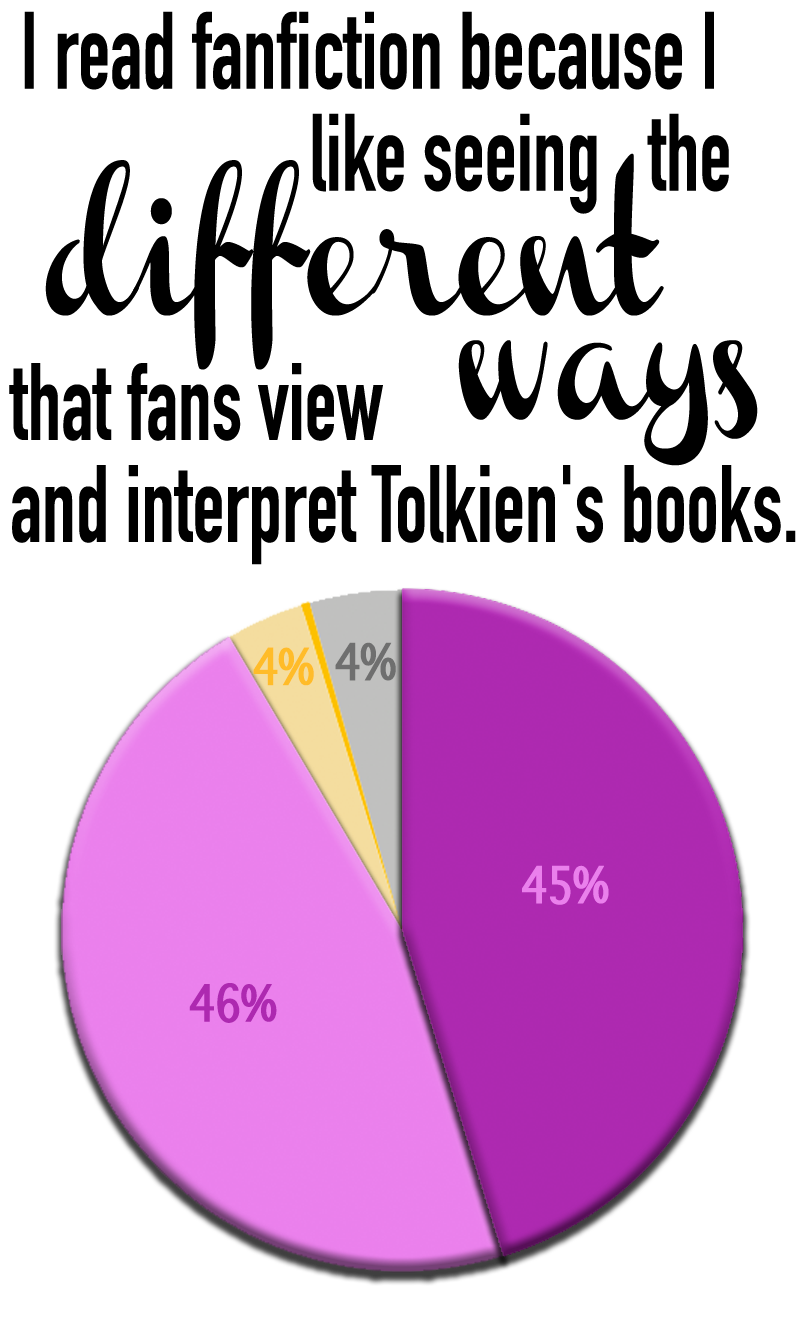

Readers overall enjoy stories that use and engage with fan-generated ideas. Two survey items related to this. One concerned the myriad diverse ways fans interact with Tolkien's books: "I read fanfiction because I like seeing the different ways that fans view and interpret Tolkien's books." The number of fans who agreed with this statement remained high and almost unchanged from 2015 to 2020: 94% and 92%, respectively.

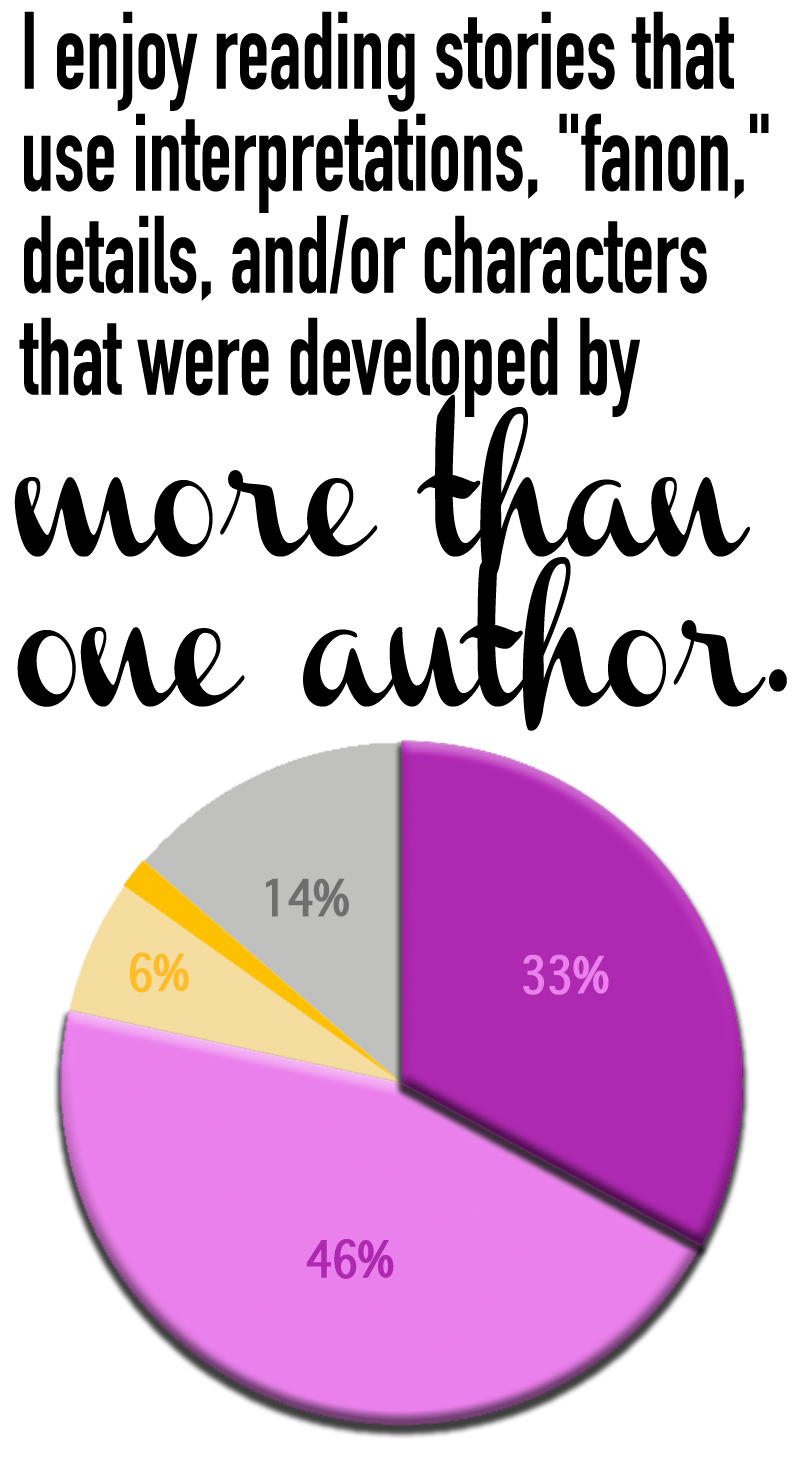

A second item tapped into reader interest more specifically around fanon, stating, "I enjoy reading stories that use interpretations, 'fanon,' details, and/or characters that were developed by more than one author. This item appeared only on the 2020 survey, where 79% of readers agreed.

Where does the difference arise between interest in writing using fanon and reading stories that utilize fanon? Both groups generally view fanon and fan authority positively, so why aren't authors embracing it more in their stories? I wonder if it doesn't point back to the notion that originality is an ideal in the creative arts—an ironic perspective when talking about fanfiction but itself indicative of how thoroughly the exaltation of originality saturates modern Western culture, even in communities that by definition embrace art forms that build on others' creative contributions. Perhaps authors want to be seen as the origin of an interpretation, characterization, or invented detail where readers care less about originality and simply want to see more of the types of stories that appeal to them—which may coalesce around a particular fanon or interpretation.

Anti-Fanon

Despite movement toward regarding fan authority more positively, this is far from a given in the Tolkien fandom, and those fans who don't enjoy fanon or put much stock in fan authority have perspectives worth acknowledging. As the data below show, about one in four fans would meet that description: a minority but not an insignificant one.

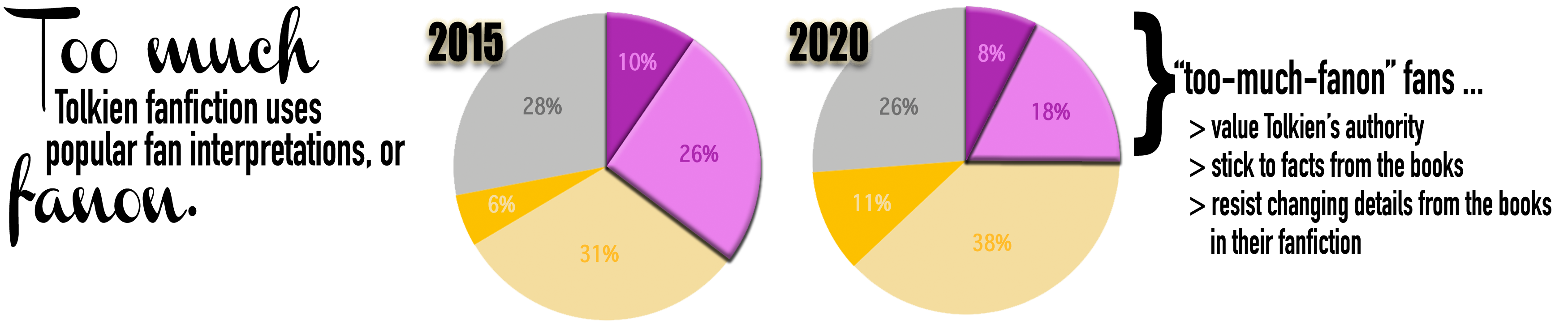

One survey item touched on this issue directly: "Too much Tolkien fanfiction uses popular fan interpretations or 'fanon.'"

Between 2015 and 2020, the number of participants who agreed with this statement dropped, from 35% to 25%. This is especially interesting given that the number of authors who enjoyed using fanon in their stories increased, but just slightly. Here, we see a more dramatic change in favor of fanon as a positive attribute in fanfiction.

Again, it is impossible for me to look at these numbers and not wonder about the possible influence of the Hobbit films on the 2015 data. Were the more than one in three participants who agreed responding in part to frustration and fatigue with certain adaptation-driven elements that were heavily present in the fandom at the time? 2020, in contrast, is a rare media-less lull: the Hobbit films were five years out of theaters, and marketing around the Rings of Power show had not yet ramped up.

I was curious if there were demographic differences between the participants who felt there was too much fanon in fanfiction and those who did not. In short, there were not: Both groups of participants were a median age of twenty-seven and, among authors, had been writing for a median of five years, which are the demographics for survey participants overall. This suggests that fandom generational differences—whether a fan began participating during a film release, for example, or early or late in the fandom's history—are not at play here.

Where I did see a difference was when looking at how the participants who felt there was too much fanon in fanworks responded to various questions around Tolkien's authority. (For the sake of brevity, I'm going to call this group the too-much-fanon group.) I chose three survey items related to this topic; in all instances, this group of participants tended to favor Tolkien's authority over the fan's "right" to make alterations to the texts. Those three survey items and some analysis follow.

- When writing fanfiction, I consider Tolkien's views on canon. As discussed above, 67% of authors agreed with this statement. The too-much-fanon participants, however, agreed 78% of the time, showing an increased preference for Tolkien's views on his canon over participants overall.

- When writing fanfiction, it is important to me to stick to the facts that Tolkien gave in his books. This item gets into the actual practice of fanfiction: How do authors make choices around canon when crafting their stories? 45% of participants overall agreed with this statement. Among the too-much-fanon group, the number increases to 61%. In other words, this group, when writing their own stories, is adhering more closely to the texts as Tolkien wrote them.

- I will change details from canon in my fanfiction if it makes the story better. This item is somewhat of a counterpoint to the item discussed above, assessing whether authors feel they have the "right" to make changes if it benefits their story. Participants who agree with this item grant authority to fan authors above the original creator (Tolkien) in these instances. 72% of participants overall agree with the statement. They are not going to produce what they see as an inferior story simply to adhere to the canon. Among the too-much-fanon authors, however, only 56% agreed. Again, they are prioritizing adherence to the canon and Tolkien's authority over fans' creative choices.

Conclusion

Taken all together, the Tolkien fanfiction fandom appears to be moving toward a greater acceptance of fanon, fan-generated ideas, and fan authority more generally. Historically (and acknowledging that there was significant variability between individual fanfiction communities), this wasn't always the case. While fanfiction has been depicted in fan studies scholarship as a freewheeling reclamation of fan authority to take beloved texts and "make them one's own," the atmosphere in many Tolkien fanfiction communities was much more restrained. Successful fanfiction made art within the sometimes brittle confines of the canon. In this context, fanon has little value or even becomes disdainful.

Yet it clearly existed and therefore had an appeal to someone. And truly, as a fanfiction writer myself who was active during the early years on the online fanfiction fandom, I'd challenge any writer to produce fanfiction devoid of fanon and other fan theories. The dismissal of fanon as a valid phenomenon, then, had more to do with signaling that Tolkien's authority was the one that held sway rather than a realistic depiction of the actual role of interactions with fellow fans, their ideas, and their work.

However, both historical evidence—such as the growing presence of pro-fanon events—and survey data suggest that fan attitudes have not only shifted but are continuing to shift. The force that we—fanfiction writers—exert on each other and each others' work is real and significant, and it is no less frivolous a consideration than the complex questions surrounding canon. Fanon and fan theories are conversations among fans: a way of responding to each others' ideas and seeing them through to fruition. They posit: If this is true, this is how the legendarium looks, using all the art of creating a Secondary World to make it believable, both on its own terms and within the context of the legendarium.

Works Cited

Tinni, Canon? No! It's Fanon!, Sept. 29, 2008 (via Wayback Machine).

Very interesting, Dawn! I…

Very interesting, Dawn!

I agree that the notion of popularity probably has an impact here, as well as questions of authority.

While some fan writers might be happy to take up popular fanons as a shared sandbox, others might reject fanons because they are too popular for their taste, but be happy to take inspiration from conversations with a small group of fans with shared interests and might even put that into a different mental category than "fanon".

The shading of meaning…

The shading of meaning between "headcanon" and "fanon" (which Araloth discusses below) is interesting and gets to your last point, I think. There are definitely different things happening here; an idea fostered in a small community or among a group of friends feels different than a "fanon" that has been around for decades and its origins long obscured. (Now THERE is an interesting avenue of research! The origins of fanons ... I'm walking away before I'm tempted. :D) Interestingly, I wonder if the connection to community vs. authority is at play here too, with the former clearly a manifestation of community and the other possibly perceived as authority (and possibly resented on those grounds too as competing too much with Tolkien's authority).

Thank you always for commenting!

Looking at fanon/canon

Enjoyable and fascinating article, particularly the changes over time coming out of the survey data. I only started reading fanfiction around five years ago. In the beginning it was generally canon-compliant stories, then seamlessly slipped into canon-adjacent fanon and ships that appealed, but has now evolved into anything with a good story - whether canon, fanon or something new.

I imagine that the television series The Rings of Power will generate, or already has generated by its nature, some new fanon. And I wonder how much further that will push the data towards fanon acceptance in a future survey.

It's interesting to me how…

It's interesting to me how many people describe trajectories similar to yours. Araloth, in the comment below, does as well, and my "fandom journey" would be similar too. I remember, as a new and fairly youngish fan who still had not read most of the texts, my sense was that, the more I read, the more solid my understanding of "canon" would become, and in fact, the opposite happened: the more I read, the more precarious the concept of "canon" seemed. Instead, it became up to fans to stitch everything together and make sense of it, and I began to perceive canon not as lines I had to color within but as a medium in which I worked creatively. I would have once described myself as canon-compliant; that is not true now.

I am interested to see, in the next survey in 2025, if/how RoP has affected the results. Right now, the show does not seem to be generating a lot of fanworks ... at least not when one considers it alongside the two film trilogies. AO3 presently has about 1700 RoP stories archived. That could change as the show evolves, especially if it attracts new fans (which seems to be the majority impact of the film trilogies: bringing in new fans who, if they stay in the fandom, almost always go on to become bookverse fans, according to my data, but of course exert an impact during their time as filmverse fans and creators). I have to admit that I am hankering for a third data set because, right now, some of what I'm seeing related to canon, fanon, and the films could be anomalies. I feel like the third data set is where I can speak of emerging patterns with a bit more confidence.

Thanks so much for commenting!

This is a super interesting…

This is a super interesting read! When I was most active in fandom around the 2009-2010 mark, in my late teens, Tumblr was only just beginning to take off as a place for fandom. I know that thanks to Tumblr a lot of younger millenials and Gen Z kids began to widely use terms like headcanon rather than fanon, both to denote their own personal interpretations of their favourite works and in reference to other people's fan theories.

I've noticed a loooot of younger fans are pretty open about loving fanfiction in general. They tend to be proud of their headcanons, and definitely do write towards other fans who share them. And I think the change in culture there is notable, as is the word choice for fan theories. Headcanon seems to have a much more positive connotation than the fanon of the 2000s. Maybe it's because the term headcanon implies that the fan is clearly expressing that it's not canon and they are not claiming it is, that it's entirely personal, and it gives the impression of having put serious thought into why they like a particular theory - whereas fanon carries that negative association with laziness, immaturity, or fans overstepping themselves. I also remember that if someone posted an 'uncanonical' fic on FFN when I was most active, they would get absolutely shredded - but if you did the same on ao3, no one would bat an eyelid.

There's a lot to think about here, but I would also add that culturally, things like queerness are far more accepted among younger people in general, so there is much more eager embracing of things like the slash pairings or gender swaps that make up a lot of headcanon/fanon today - despite Tolkien's having been religious and only ever having written het pairings himself. I know that the participants whose data you have are mostly not super young fans, but I think younger fans, with their increased internet access, their increased confidence in owning that they like fanfiction, and their own eager contributions to the fandom have certainly had a wide impact that can't be underestimated.

I also remember the…

I also remember the transition from fanon --> headcanon around that time. As a slightly older fan (2004-2005), I found it cringey and honestly still find it makes my shoulders go up around my ears a little, like hearing the word "moist." "Fanon," despite its sometimes negative connotations, does not create this same reaction, but I suspect it is not the word itself so much as the sense that many of us who had been in fandom for several years when "headcanon" and other Tumblr-popularized terms emerged had that new fans at the time had little regard for the cultures of which we were already part. In other words, I had officially entered fandom middle age! :D

Thinking about the two terms, to me, as that older generation of fans, they had slightly different meanings. A fanon is long-established fan-generated idea or theory that has received popular acceptance/support, often to the point that some fans don't realize it's not canon, and the origins are obscured. A headcanon has a much smaller scope, even just one person. Where there is overlap, in my use of the terms, is when multiple people begin using the same headcanon. When does that become a fanon? (To me, it would be the loss of knowledge of its origins for most fans and its use across discrete social groups.)

It has definitely been interesting, in my twenty years of fandom, to also observe what you note about the acceptance of "noncanonical" fanworks. I wonder sometimes if this is at least partly due to fans from that older generation getting a much-needed reality check. Fanon, headcanon, AU ... none of it changed the books or "ruined Tolkien" or even made it so that most Tolkien fans can't distinguish between what he wrote and what fans have invented. In my early years, there was often this crusading sense of preserving the books/canon from corruption. I've rolled my eyes hard at these folks over the years, but with the benefit of the distance of time, I can summon up some empathy for them now because, in the early 2000s, online fandom/fanfiction was so new and they just didn't know. Many had come from pre-internet book fandom, and I imagine they feared that the fandom they valued would disappear under an onslaught of filmverse fans more interested in Orlando Bloom's underwear than the origins of Orcs. (Part of my ability to empathize has come from having to sit with my own feelings around RoP and the SWG: What if RoP takes off, and the SWG receives an onslaught of showverse fans/fanworks? My beliefs say we must accept them, but those beliefs are definitely challenged when it is your labor and your dollars sustaining the spaces they're using to "do fandom" in a way you don't particularly enjoy. I do hope that, if it were to happen, I can be more magnanimous and kind than some of the early 2000s bookverse fans were toward film fans ... but I "get" early canatics as I didn't used to in my worries around these questions.)

All of that to say that your point about younger fans and their increased comfort with fandom/fanworks makes a lot of sense: They know the world is not going to end if someone makes Maedhros gay. Every copy of The Silmarillion will not change. People will know what Tolkien wrote and the fan theories they enjoy and the difference between them.

Thanks so much for commenting!

Thank you for replying, Dawn…

Thank you for replying, Dawn! Haha I definitely understand the cringe :D

Yep, I wasn't sure whether I was conflating the terms too much in my reply - there's certainly a difference, and also an overlap. I've seen a lot of headcanons become popular fan theories thanks to places like Tumblr where ideas can rapidly spread and be reblogged everywhere in a matter of days or hours!

I do think there's been a longstanding attitude in the online Tolkien fandom where more established fans tend to side-eye newcomers - probably born from, as you say, the fear that new fans were more interested in Orlando's underthings than the fascinating lore of Middle-Earth. I remember being a little nervous when the Hobbit films came out as well, having been a canon/lore geek for long enough and also having read fic for long enough that I'd seen some truly bizarre fan theories and ideas. I think part of it is this: when you truly love a text so much, it can feel intrusive to watch other people spreading various theories and imposing them on a beloved world - I can understand that to early 2000s fans, with the internet only just taking off, it probably would evoke that sense of something sacred being destroyed. I can empathise with that. I've seen some fan theories that were just...not it, and it can be annoying and a little disconcerting, especially when it comes to the smuttier ideas - no shade, some people just enjoy some strange sounding stuff.

But yeah, The Silmarillion is not going to burst into flames or rewrite itself if someone really just, you know, wants to write a gay Elf. I'm sure most fans who have been around for long enough have had the chance to put their collective shirts back on and realise that the original text is never going to be 'corrupted' no matter how many weird and pervasive theories make the rounds. And most people know to steer clear of tags or summaries that they don't like the look of. The ol' 'don't like, don't read' a lot of teens used to defensively slap onto their summaries back in the day to pre-empt the descent of the canatics probably still applies!