Doom and Ascent: The Argument of ‘Beowulf: the Monsters and the Critics’ by Simon J. Cook

Posted on 12 October 2024; updated on 19 November 2024

This article is part of the newsletter column A Sense of History.

Beowulf is … an heroic-elegiac poem; and in a sense all its first 3,136 lines are the prelude to a dirge: him þa gegiredan Geata leode ad ofer eorðan unwaclicne: one of the most moving ever written.1

Some emerge from J.R.R. Tolkien's 'Beowulf: the Monsters and the Critics' as ducks from water, escaping a deep lake of ideas with scarce a wetting. Others hold up a thimble, and fall insensible. Criticism serves in new bottles the naïve platitudes of Edwardian taste, bankrupted in 1914 and swept away by Tolkien's performance. The secondary literature reveals the creep of complacence in our own times, marked by a supercilious historical awkwardness that disparages what it does not understand and turns away from that which it fears.

Twoscore and a few years ago, the pioneers of Tolkien criticism perceived that 'Beowulf: the Monsters and the Critics' was vitally connected to The Lord of the Rings. But they failed to catch the argument, reconstructed the allegory, and projected their reconstructed art onto Tolkien's prose. The result was a mess. The essay was first read by Jane Chance (1979) as an assault on scholarship in the name of art, and then dismissed by Tom Shippey (1982) as founded on irrational and politically dubious mysticism.

One reason that Tolkien's argument is difficult to comprehend is that we still think of history as progress, a modern dogma not shared by the author of Beowulf. A more general obstacle arises because Tolkien's performance is a cunningly fashioned and marvelous work of learned craft. While the Old English of Beowulf demands special study, we struggle today with a weighty argument in modern English. The root problem, however, is that Tolkien speaks of death, and we in our (relatively) safe homes don’t wish to see even the half of what he says. Looking for fairy-story you are shown doom, and decide that this particular work of Tolkien is not your cup of tea.

The argument is not so hard to follow. What may appear a maze is a simple enough structure to navigate, easily drawn; the only trick is catching the tower again at the end. Beginning with the criticism that Tolkien set out to overturn, our first business will be to hunt for a map; only with a diagram in hand will we enter Tolkien's argument. His first step passes over the outer edges of the poem, his second arrives at its center, where we find mythical monsters and our courage when we face them. At the end, as we attempt to return through a dirge for the dead, Tolkien names the poem heroic elegy (see the header to the post). But he leaves it to us to comprehend for ourselves the significance of his bleak conclusion.

For my part, I conclude with two comments reflecting my own interests. The first concerns the chief friend of the allegory, and points to the historical dimension of Tolkien's literary criticism. The second wraps up my account of the allegorical tower, the holy grail of this series of posts.

A Picture of Criticism

Tolkien's allegory of the tower divides the critics of Beowulf into friends and descendants of the Anglo-Saxon builder. As observed in earlier posts, first Jane Chance (First Brick in the Wall) and then Tom Shippey (Peaks of Taniquetil) vanished the descendants. Chance remade Tolkien's allegory as a tale of a lonely artist and his destructive friends, a silly parable of how art is ruined by scholarly criticism, and Shippey followed Chance.2

Vanishing the descendants of the allegory is a first step to vanishing the argument of 'Beowulf: the Monsters and the Critics'. Tolkien's intention is to overturn the critical verdict of the great (and late) W.P. Ker, the chief descendant. The descendants are those critics who, rather than demolish the tower, complain of its proportions. Vanishing the descendants vanishes the argument because it is with the descendants that Tolkien is arguing.

Our pursuit of Tolkien's argument begins in The Dark Ages (1904), wherein Ker surveyed the fragments of the poetic heritage of the Germanic North. When Tolkien delivered his lecture in 1936, Ker's withering criticism of the greatest surviving Old English poem had stood as authoritative for three decades. Ker began by nodding to the secondary literature, giving a recognizable source for Tolkien's division of critics into foolish friends and staid descendants:

A reasonable view of the merit of Beowulf is not impossible, though rash enthusiasm may have made too much of it, while a correct and sober taste may have too contemptuously refused to attend to Grendel or the Firedrake. The fault of Beowulf is that there is nothing much in the story.

Having summarized the 'too simple' story, and contrasted the beautiful dignity of style with the curiously weak—'in a sense preposterous'—construction, Ker, the voice of erudite Edwardian criticism, concluded with a sentence that we may picture as a cruel knife that hurt Tolkien sore, a wound that long pained him—until, in November 1936, he removed the splinter from his heart by an alchemy of imagination that transformed Ker’s spatial metaphor into a map of the world of the old Northern stories, surrounded by the Shoreless Sea and with Doom at the center:

Yet with this radical defect, a disproportion that puts the irrelevances in the centre and the serious things on the outer edges, the poem of Beowulf is unmistakably heroic and weighty.3

This sentence, or rather the attempt to overturn it, is the kernel of Tolkien's British Academy lecture. As noted in an earlier post, in 1933 Tolkien pictured Beowulf as a rock garden, a pattern juxtaposing old stones and commonplace flowers. This is the image to hold in mind while following the argument of 'Beowulf: the Monsters and the Critics', though it falls away into the distance in his conclusion.

The original image of a rock garden draws out the spatial metaphor of Ker's criticism. The now forgotten but once well-known heroic legends alluded to in the poem are stones standing on the outer edges, the monsters are terrible stones at the center, within the shadow of which a solitary flower blossoms and then dies. Such flowers are scattered all around the rock garden, symbols of the courage of the heathen heroes of old. The rock garden is a diagram, which maps the poem and establishes the primary points of contention, namely the significance of the outer stones, the inner stones and the solitary flower, and the design as a whole.

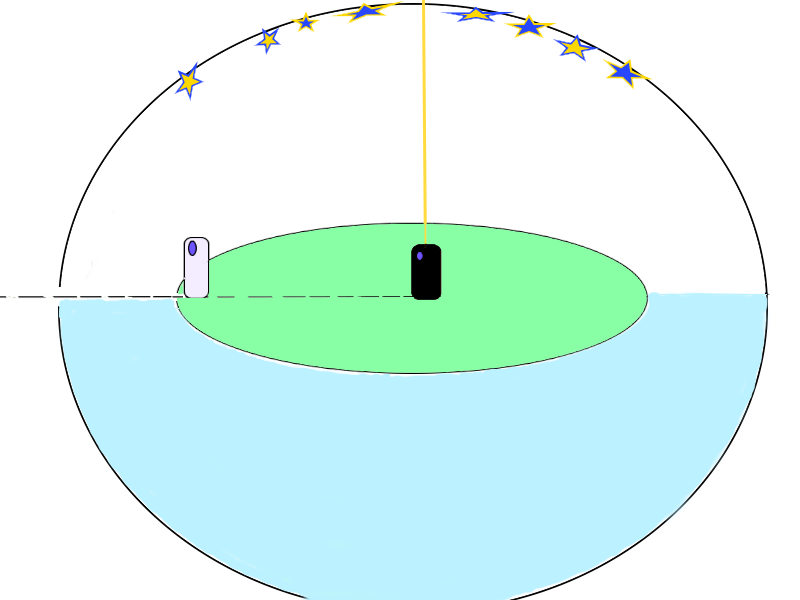

(The flat green disc world in the image Fusion may serve as a picture of the rock garden, if you are prepared to make the following adjustments: Remove the tower and the shoreless sea on the horizontal, as also the sphere of the heavens and the world all around; scatter some smaller stones around the periphery of the green disc to give the stones that the descendants like, and picture the dark tower at the center as actually three monstrous stones; now scatter some commonplace flowers, placing the brightest at the very center, standing for a while in the shadow of the monstrous stones.)

The complaint of the descendants is that the monsters at the center pull the hero into a thin folktale. Beowulf battles foes without eloquence and with no claim to our sympathy—there is no irreconcilable conflict of duty that makes for recognizable drama. Meanwhile, on the outer edges of the poem, we catch glimpses of older stories, with mortal heroes who battle each other, caught in a mesh of circumstances beyond their control. These Edwardian scholars want to read stories about heathen heroes like Uhtred son of Uhtred of Bernard Cornwell's The Last Kingdom (2004), grimy swordsmen who talk of wyrd, defy their enemies, and fail in love. Such tales they deem more worthy than a wilderness of dragons.

Historical Periphery, Mythical Center

The first stitching of Tolkien's argument draws the outer stones as historical and names the inner stones mythical, with the stones on the outer edges dealt with almost by allegory alone. The significance of the allusions to now forgotten heroic legends is revealed by juxtaposition with foolish modern friends, who fail to discern the hand of the Anglo-Saxon author. The friends of the allegory do not see the elegiac unity of the poem, only an amalgam of ancient heathen oral tradition, and so illustrate the spell of this very old art still at work.

Tolkien accepts the historical judgment of Ker's disciple Chambers that the poem was composed in the age of Bede. As a tale of the heathen past, Beowulf is a work of 'historical fiction'. Tolkien observes that the peripheral stones of the rock garden—the allusions to various historical legends—work a literary spell, conjuring a sense of heathen antiquity. The conviction of the modern friends that they see before them unalloyed heathen tradition suggests that they have been caught by this spell.

The friends are useful idiots, beyond the pale of an argument conducted with the descendants. From the perspective of Ker's criticism, the confusion of the friends justifies the poet's placing of the outer stones of the rock garden. Their failure to distinguish heathen antiquity and Anglo-Saxon art sets up Tolkien's core argument that the image of the heathen past is made by an Anglo-Saxon art of fusion.

The core of 'Beowulf: the Monsters and the Critics' is a demonstration that the central stones of the rock garden fuse Christian and heathen eschatologies (notions of the end). The demonstration requires an initial terminological shift, achieved in the first passage of argument. On concluding his allegory of the tower, Tolkien engages head-to-head with the critics. Passing rapidly over a babel of friendly voices, he quotes at length three critical verdicts of the descendants, criticizing each to the same end. Tolkien's ostensible point is that a good craftsman who threw talent away on a silly theme is improbable—more plausible is that the critics have failed to discern the poet's design. Yet almost every paragraph of several pages serves the rhetorical purpose of substituting folklore, as the operative adjective for the center of the poem, with myth.4 With the more elevated term in hand, Tolkien is ready to reveal the monsters as made by fusion.

Doom: Demonstration of Fusion

We are looking out from the top of the tower of the allegory, in a passage quoted in both my June posts (Beleriand in Beowulf and Passing Ships). Surveying the entire panoramic view, Tolkien gestures to the Shoreless Sea that the Anglo-Saxon poet is said to look out upon in the concluding line of the allegory of the tower. But he now directs our gaze inland to a mythological image of Doom. We stand on the tower but look out upon the rock garden, and monsters await at the center.

Tolkien demonstrates that, whatever confusion we may feel as we gaze upon the shifting, shadowy faces of monstrous death that is this mythical picture of Doom, analysis reveals a nice fusion of two eschatologies. The marvel is the economy of the demonstration. Quoting one text by Chambers and another by Ker, Tolkien reveals the mythical monsters as bearing both Christian and heathen meanings, thereby using the words of the two chief descendants to demonstrate that, rather than confusion, Beowulf is fusion.

The demonstration steps from the poem to two secondary texts. First, Tolkien argues that descent of the heathen monsters from Cain marks them in the poem as enemies of the Christian God. Second, he reads a long quotation from an essay by Chambers, underlining that, unlike the mythology of Homeric Greece, in the North the gods are our allies against the monsters.5 Finally, Tolkien reads again from Ker's Dark Ages, only now from his praise of the courage of the doomed gods in the most famous of the Eddic poems, the Völuspá. Ker reads the Icelandic myth of Ragnarök and Tolkien holds up Beowulf as an earlier, individual, and godless version of the same eschatological image of Doom.6

The demonstration rests on prior analysis of Anglo-Saxon notions of Time, an attribution to the old poet of a clear distinction between immortality and eternity. This was performed by Tolkien with The Fall of Númenor, wherein a flat world of immortal gods and Elves becomes round.7 The Northern gods are like Tolkien's Elves, immortals who endure as long as the world, unless slain. To such a conception of the world the Church with its small library introduced a hitherto unsuspected realm, Eternity, pictured as outside of Time, beyond the great Ptolemaic sphere on which adhere the fixed stars, where the soul journeys after death (the vertical gold line in Fusion).

The Time of heathen tradition is as long as the world, doom our certain end, and this sober image of reality is not contradicted by the good tidings of 'a possibility of eternal victory'.8 The relationship is complementary and the balance unstable, as new hope overshadows old despair. But in this poem the pregnant potential issues in the details while the general fusion is balanced. The new Ptolemaic circle of Heaven frames the ancient heathen vision of the flat-world. The result is a picture of the imagination of an ancient past, framed from the outside; a modern design that draws out the mythological background that the poet has discerned behind the oral tales received from the heathen past.

(This is all illustrated in the image Fusion, or so I hope.)

The descendants mourned the lost heroic lays and sniffed at a folktale. Opening up the poem, Tolkien reveals a world from which the gods long ago departed as one heathen hero walks alone to his doom. The poet has embraced the new learning, biblical, astronomical, and historiographical, and used it all to paint a heathen hero of old in mythological terms, rendering him intelligible to an Anglo-Saxon audience. So was constructed a moving image of a world now lost, the ancient past of the modern English, which from their own shores they can only ever imagine; a poem of a design of a kind that nobody before the War had ever considered.

Theory of Courage

It is this intensity of courage that distinguishes the Northern mythology (and Icelandic literature generally) from all others. The last word of the Northmen before their entry into the larger world of Southern culture, their last independent guess at the secret of the Universe, is given in the Twilight of the Gods. As far as it goes, and as a working theory, it is absolutely impregnable. It is the assertion of the individual freedom against all the terrors and temptations of the world. It is absolute resistance, perfect because without hope.9

Stirring stuff, not Tolkien. Ker in The Dark Ages reflects on 'The Twilight of the Gods' and the courage of the Northern gods who deem their defeat no refutation. Tolkien paraphrases Ker in his British Academy lecture, applying his words to Beowulf. Edwardian literary critic and Icelandic source are today forgotten, but the words live on in quotations presented as 'Tolkien on the Northern courage'. Yet Ker was celebrating heathen animal spirits before the arising of German National Socialism. By 1936, any theory of a specifically Northern heroic courage demanded urgent revaluation.

No less than the monsters, courage in Beowulf is a fusion. The core of 'Beowulf: the Monsters and the Critics' is the discovery of dual symbolism lurking beneath the shadows of the image of Doom. But so far as I can make out, Tolkien saw the whole poem in terms of fusion. Indeed, elsewhere he imagined this fusion beyond the rock garden's western margins, through The Silmarillion and ultimately all the way back to the Creation (the song of which from Heorot maddens Grendel). In any case, heroic courage looks different in the face of monsters that fuse mythological traditions:

Man alien in a hostile world, engaged in a struggle which he cannot win while the world lasts, is assured that his foes are the foes also of Dryhten [the Christian Lord], that his courage noble in itself is also the highest loyalty: so said thyle and clerk.10

These are Tolkien's words, in dialogue with Chambers, picturing the alchemy of conversion. Loyalty to a lord was surely always bound up in aristocratic heathen notions of courage. Chambers and Tolkien agreed that loyalty to the Eternal Lord of Heaven makes Beowulf almost a medieval Christian knight. For an academic argument conducted in his own day, Tolkien draws the heroic courage of Beowulf as a solitary flower that blossoms and dies in the shadow of the terrible central stones. This picture of the fusion in Beowulf he then refashioned in a fairy-story for our own day, which knows no Ptolemaic sphere of Heaven but only the sky: a fusion made with two flowers, with Sam cradling nine-fingered Frodo on the edge of Doom.

Yet without Beowulf—to me at any rate—the Germanic hero that Chambers insists on having and says that the 'old poets' would not have sold for a 'wilderness of dragons,' is an animal in a trap, fierce, sad, brave, and bloody, but not very intelligible (nor always very intelligent), as moving as a baited badger.11

The scholarly tome on Beowulf that J.R.R. Tolkien never wrote would have elaborated this image of heathen animal spirits in ways I cannot imagine. For a sizeable tome, we have instead The Lord of the Rings, a modern fairy-story wherein the badger steps out of his hole a Hobbit on an adventure, a quest down the Straight Road all the way to Mount Doom—and back again, concluding with a ship voyage into the West. Where fusion once made the heathen hero almost a Christian knight, we now have the Hobbits of the Shire.

For scholarly comment we have nearly only 'Beowulf: the Monsters and the Critics', though this is more than a little. Consider this passage on heroic courage, circled back in my post 1936, and grounded on the historical observation that, prior to conversion, trust in the old gods had already faded in Scandinavia. Tolkien begins by paraphrasing Ker on the northern theory of courage:

'As a working theory absolutely impregnable.’ So potent is it, that while the older southern imagination has faded for ever into literary ornament, the northern has power, as it were, to revive its spirit even in our own times. It can work, even as it did work with the goðlauss viking, without gods: martial heroism as its own end. But we may remember that the poet of Beowulf saw clearly: the wages of heroism is death.12

Many different fusions await the courage of the vanished North, while the very idea of this heathen courage without fusion is a confusion. This heathen courage was once embedded in a wider mythology, now almost entirely lost to us. Abstracted from language and culture, as it is only in the modern day, the theory degenerates into a creed of naked will, a descent into nihilism and a cult of war, a road to fascism. The art of fusion draws a lost world together with our own to rescue that past (and ourselves) from oblivion.

On Tolkien's Conclusion: Elegy

Scroll up for the header to this post: Tolkien declares the first 3,136 lines of the poem the prelude to a dirge sung at a heathen funeral. After the mighty courage of the hero comes the bitter mourning of the survivors. And with the burial of the hero the poem concludes and we depart this lost world of the past, looking down on it a last time from the top of a tower that is an Anglo-Saxon elegy.

The header is all I give from the concluding pages of 'Beowulf: the Monsters and the Critics'. Instead, I provide a footnote by E.V. Gordon, who does not appear in Tolkien's allegories of the poem and was his colleague and good friend at Leeds University in the early 1920s. Gordon's edition of The Battle of Maldon (1937) includes the following sentence, which I read as a sign-post to a conclusion hammered out in long talks between two Coalbiters. Gordon says, 'Beowulf, usually accounted primarily heroic and epic, is in its ultimate aim elegiac.' His footnote elaborates.

Beowulf is regarded as an elegy on the common Old English theme lif is læne. The relation of the two parts of the poem is deliberate contrast: the first part shows the hero in his youth at the height of his physical prowess, and contains a series of heroic pictures designed to exhibit his strength and nobility; the second part shows the sadness of his old age and death, and implies that with him passes the prosperity of his people. Thus all that is noblest in life passes and cannot be replaced. The second part is not merely an additional adventure; it gives the meaning of the whole poem. There can be no doubt of the essential unity of Beowulf: the whole poem is carefully planned to show the tragedy and importance of its elegiac theme.13

Tolkien says little more. Do not seek an answer to the riddle of the universe in a defense of an Anglo-Saxon reflection on despair! All Tolkien does is follow the poet before him, leading us to look upon Doom. There he leaves us, to accept or not, as we will.

Observe how Gordon circles kingship, which the hero Beowulf steps into, and so shades the end of his personal battles with monsters into a dramatization of history (compare the Danish Scylding dynasty). But also observe how he says nothing of heathen antiquity nor offers a glimpse of myth, tacitly placing both beyond the limits of footnote. Tolkien's British Academy lecture arrives at this elegiac conclusion by way of both, an argument about fusion and a reflection on the place of mythology in any comprehension of ancient history.

Gordon and Tolkien perceive elegy in the unity of the poem, its balance, with an end that illuminates the beginning—with all the celebration of courage in the face of mythical doom, prelude to the moving funeral dirge of a doomed people. Any theory of courage in this poem is completed only with its final payment, death, and we leave the poem with the hopeless grief of the survivors who mourn on the ground. With the recollection that we are not on this ground but looking down upon it from more modern times, the whole structure of balance and juxtaposition drawn out by the rock garden vanishes, to leave as standing atop an Anglo-Saxon tower, looking out on both sides of the Straight Road.

In conclusion, the rock garden falls away beneath our feet to leave us looking out upon an empty sea. As we exit the rock garden by funeral dirge, we discover ourselves once again looking down on a world that has passed. The allegorical tower at the entrance takes its meaning from the end of the argument that it introduces, and gives the meaning of Tolkien's conclusion.

Historical Epilogue

Compare Gordon and Tolkien on the artful end of Beowulf with a passage from The Heroic Age (1912), penned by Hector Munro Chadwick, Elrington and Bosworth Professor of Anglo-Saxon at Cambridge, Tolkien's more senior opposite number in Cambridge:

In the long account of Beowulf’s obsequies—beginning with the dying king’s injunction to construct for him a lofty barrow on the edge of the cliff, and ending with the scene of the twelve princes riding round the barrow, proclaiming the dead man’s exploits—we have the most detailed description of an early Teutonic funeral which has come down to us, and one of which the accuracy is confirmed in every point by archaeological or contemporary literary evidence. Such an account must have been composed within living memory of a time when ceremonies of this kind were still actually in use.14

One way to tell what (if anything) you have gathered from reading 'Beowulf: the Monsters and the Critics' (as also this post) is counting out the different ways in which the essay calls out the author of this passage as a fool. The allegory of the tower is half mythical-metaphor (see below) and half academic saga. As saga, we might picture the British Academy as a Thing, and hear in his essay J.R.R. Tolkien stepping up to speak for justice in the name of an old poet, who died long ago and whose proper name is forgotten. With his allegory Tolkien draws up his charges, which place Chadwick beyond the pale. Stepping from allegory to argument Tolkien declares the hope that his allegory will be deemed just. He was not explaining to future students of English that his tale of the tower accords with some canonical idea of allegory, as Shippey has told us.15 Rather, he was asserting his belief that his argument would demonstrate to the distinguished assembly the justness of his charges against his various colleagues.

Back in the 1980s, the critics read Tolkien's essay and dimly perceived that at the root of all the mischief was some 'historical document fallacy'. The insight was correct, and all that has been overlooked is the revolution of Tolkien's thought, which by its end has pointed, silently yet demonstrably, to the nature and meaning of Beowulf when read, carefully, as historical document. By the end of Tolkien's argument, the author of Beowulf appears shoulder to shoulder with the Venerable Bede, an illustration of another side of a rare discovery of an idea of History, witnessed at the very beginning of English literacy and identity:

In Beowulf we have, then, an historical poem about the pagan past, or an attempt at one—literal historical fidelity founded on modern research was, of course, not attempted. It is a poem by a learned man writing of old times, who looking back on the heroism and sorrow feels in them something permanent and something symbolical.16

Beowulf is not an actual picture of historic Denmark or Geatland or Sweden about A.D. 500. But it is (if with certain minor defects) on a general view a self-consistent picture, a construction bearing clearly the marks of design and thought.17

Tolkien's Fusion

The allegory of the tower is Tolkien's version of an exordium, an artful sketch of the pattern about to be woven. Stepping to the end of his argument we step back from the central fusion to encounter mourning and confusion on the outer edges. Those heathen heroes under the sky who mourn the passing of the mythical king at the close of the exordium and those who sing a funeral dirge at Beowulf's funeral frame this poem. Looking down on these heathens of old from the top of an Anglo-Saxon tower, Tolkien declares an elegiac work of historical imagination.

Fusion draws out what the tower hides by highlighting, namely a smudge in the original image of the rock garden. This smudge appeared when Tolkien drew out Ker's criticism without quibbling that myth appears also on the periphery of the poem, at the beginning.

The exordium to Beowulf is remade by Tolkien into the allegory of the tower, and does not appear as an element in his argument. As recounted in Straight Road, the exordium recalls the ancient myth of the king who is sent to his people by unnamed others who dwell beyond the Shoreless Sea. The tower appears in place of the funeral ship, offering straight sight on the vanished past, in place of fragmented and confused memory. What we might call the exordium-stone stands at the entrance to the rock garden, located on the poem's outer edge, where we begin.

The revised allegory is a working up of this other myth in the poem. Tolkien now gathers the old stones that made the rock garden and pictures the making of a tower, a new illustration of fusion. Best to imagine superimposition, with the old image of the rock garden enduring and the tower standing where once appeared a smudged stone. An instance of fusion made by the critic out of the original exordium, and in the mirror of the fusion discovered at the center of the poem. The rock garden disappears from view, but only because we have yet to adjust our vision to take in the moving panoramic views from the tower. The tower of Tolkien's exordium is a demonstration that our critic has mastered not only the technique of but also the vision in the Anglo-Saxon art.

As illustrated in the image Fusion, the Straight Road draws out the relationship between the exordium-stone and the monstrous central stones. In Tolkien's cosmic myth of the world changing, this Straight Road is drawn by Elendil, who sails out of ancient myth and into the round world of history, to continue inland all the way to Mordor. Henceforth, the sea-portion of the Straight Road is lost, remaining only as memory, recalled in fragments of ancient myth. For us is given only to tread the inland portion of the Straight Road, which leads to the same end in the conclusion of our turn on the spiral staircase hidden within the tower. Now, we too remain only as memory.

Dedication

This post is dedicated to Dawn Walls-Thumma, the only Tolkien scholar I know who has also perceived the historical dimension of Tolkien's literary craft. Dawn's example long ago inspired me to try my own hand at fan fiction, which proved a turning point in my study of Tolkien. All of my Sense of History posts have been edited by Dawn, whose editing is superior to that provided by many an academic journal. Above all, one year ago, when my mind melted away for some months in the face of horror for me hitherto unimaginable, Dawn stepped into the playground of the Tolkien academics and blew her whistle. That was deeply appreciated on my part, but I know that she did this not for me but out of a commitment to civic discourse untainted by the corruption of power, and that is why I dedicate this post to her.

Works Cited

1. Monsters and the Critics, and Other Essays, "Beowulf: The Monsters and the Critics," lines 3137-8: "him þa gegiredan Geata leode ad ofer eorðan unwaclicne" ("For him the Geatish lords a pyre prepared upon the earth, not niggardly.")

2. Shippey’s early reading of Tolkien's "famous British Academy lecture" is groping in the right direction (Tom A. Shippey, "Creation from Philology in The Lord of the Rings" in J.R.R. Tolkien, Scholar and Storyteller: Essays in Memoriam, eds. Mary Salu and Robert T. Farrell [Ithica: Cornell University Press, 1979], 286-316, 310). Then he read Jane Chance's Tolkien's Art: A Mythology for England (1979). His review of Chance in Notes & Queries (1980, pp. 570-2) brutally demolishes her monograph as an "Augustinian failure," pillorying a literary critic who has trespassed into the academic grounds of the philologist. Yet he concludes with a concession that turns out to hand over the keys: "There are some good points in this book. The author is entirely right to see self-images of Tolkien lurking in all the fiction …" (571). Chance is the source of Shippey's crass idea that the man in the high tower is both Beowulf poet and J.R.R. Tolkien, and the road is open to the misbegotten speculations on reincarnation and the equation of descent with Nazi ideas of blood and soil, which I held up for ridicule in Fawlty Towers one year ago this month. Obliterating her work in his public review, in private Shippey was convinced by Chance's absurd literary reading of "Beowulf: the Monsters and the Critics." The Road to Middle-earth declares Tolkien’s essay academically unsound and Shippey's strategy throughout is to recruit Tolkien as practitioner of an imaginary "pure philology," a category newly invented because the champion of philology has no faith in Tolkien's scholarship.

3. W.P Ker, The Dark Ages (New York: Charles Scribner, 1904), 252-4.

4. "Beowulf: The Monsters and the Critics," 8-18 (from the allegory almost to the panoramic view from the tower—first comes a first statement of the thesis, without badgers; see footnote 11 below).

5. "Beowulf: The Monsters and the Critics," 19-20; quoting R.W. Chambers, "Beowulf and the Heroic Age in England," Foreword to Beowulf, trans. Archibald Strong (London: Constable, 1925), xxvii-xxix. This is Tolkien's favorite item of secondary literature, the first thing he gave his students after the poem.

6. Ker, Dark Ages, 57. Note Ker's note: "The term 'Twilight of the Gods' (ragnarökr), used regularly by Snorri, is probably to be taken, as Gudbrand Vigfusson explains, for a confusion with ‘Doom of the Gods’ (ragnarök) which occurs repeatedly, while the other occurs once only, in the mythological poems." For Tolkien's philological grounds for seeking ancient English mythology in the Eddas, see his Interwar introductory lecture on the Elder Edda in The Legend of Sigurd and Gudrún (London: HarperCollins, 2009), 21-2.

7. On the distinction between rounded Earth and rounded cosmos and the step between 'The Fall of Númenor' and Tolkien's Beowulf criticism, see footnote 3 of Straight Road.

8. "Beowulf: The Monsters and the Critics," 22.

9. Ker, Dark Ages, 57.

10. "Beowulf: The Monsters and the Critics," 26.

11. Beowulf and the Critics, ed. Michael Drout (Tempe, AR: Arizona Center for Medieval and Renaissance Studies, 2002), 40, 149. Cf. "Beowulf: The Monsters and the Critics," 17-18. The revised version of this passage, without the badgers, appears just before the panoramic view given on return to the tower.

12. "Beowulf: The Monsters and the Critics," 25-6.

13. E.V. Gordon, The Battle of Maldon (Methuen: London, 1937), 24; cf. "Beowulf: The Monsters and the Critics," 28: "lif is læne" ("life is fleeting").

14. H. Munro Chadwick, The Heroic Age (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1912), 53. The passage is quoted, and its author already made to appear a little foolish, in R.W. Chambers, Beowulf: An Introduction to the Poem (Cambridge: University Press: 1921), 122.

15. "Beowulf: The Monsters and the Critics" and Tom A. Shippey, The Road to Middle-earth (London: Allen & Unwin, 1982), 34, 36. Tolkien's statement: "I hope I shall show that that allegory is just—even when we consider the more recent and more perceptive critics (whose concern is in intention with literature)."

16. "Beowulf: The Monsters and the Critics," 26.

17. "Beowulf: The Monsters and the Critics," 27.

I have a lot of big feelings…

I have a lot of big feelings about this final essay in the series, being both a Tolkien person and a Beowulf person and being overly familiar with the scholarship of both. And of course being a minor character in the production of this series over the last twenty months or so, it is incredible to read the final essay and see all of the pieces come together!

Things that are swirling around in my headspace right now, after my second (and first non-distracted by copyediting) reading:

"In Beowulf we have, then, an historical poem about the pagan past, or an attempt at one—literal historical fidelity founded on modern research was, of course, not attempted. It is a poem by a learned man writing of old times, who looking back on the heroism and sorrow feels in them something permanent and something symbolical."

... I felt like could be just as easily written about Pengolodh, as the primary narrator of the Silm, someone who is interested in documenting the history of the First Age but also wants to represent something about that time in terms that are not entirely concrete—hence the missed point in, say, reading the Silm and unable to comprehend Maedhros's torment without spinning elaborate theories about how he ate bugs and drank rain, etc. (And to be clear, there is nothing wrong with that! And many fanfic writers do this all the time. I don't want to yuck anyone's yum. But there is this perception of distress I pick up sometimes, as noted above, between the historical and the mythical, where having the first makes the latter harder to accept for what it is and, more importantly, what those impossible-seeming elements in the histories represent.)

My whole-hearted congratulations on reaching the end of this series, through all the challenges life brings and actual war! I suspect I will need to return to this piece (and the entire series, now that I have the full picture to fit all the previous essays into) several more times before I fully grasp all that you've done, but I will be glad to do so. Over summer break!

And you better be actually asleep—I wrote a really long comment to ensure it!—because I've fallen down this rabbit hole and still have a newsletter to do! :D

Recalling Mark Twain

On waking this morning I found myself googling to get this: 'In 1897, Mark Twain is said to have read his own obituary, and then remarked, “The reports of my death are greatly exaggerated.”' So just to say, while I need a break from writing, there is still more to come! Not sure if that is good or bad. This is the end with regard to the 1936 material. But I have in mind a last series of around 5 posts that use the map Fusion to read the early drafts of LotR. In terms of prior content, I still have to explain how the 2 ships of the exordium become the 3 ships in Galadriel's Mirror, how an Anglo-Saxon elegy was turned around to make a 20th-century fairy-story, and how the Rings of Power were imagined in relation to the spiral staircase (and one or two other things as well). This of course hinges on the powers that be at the SWG giving the OK to this last part of the series. My apologies for any confusion. I will now read and digest the rest of your comment.

Simon

Pengolodh and the B-poet

Right! The comparison had never entered my mind, but makes immediate sense. Basically, attempting my own fan-fic helped me to see how often within Tolkien's fiction we find him continuing his 'scholarly meditations' by another mode. Now that you draw the connection it makes a lot of sense to me that with Pengolodh we find Tolkien thinking through his imagination of an unknowable Anglo-Saxon author. More broadly, ideas like this are precisely why I wanted to publish these posts on the SWG. I have read 'Return of the Shadow' more times that I can count, as also of course 'The Lord of the Rings', and have a clear notion of how the Beowulf-scholarship fed into the tale of the end of the Third Age (the first age of a round world). But (aside from 'Fall of Numenor' and 'Of the Rings of Power and the Third Age') I am keenly aware how superficial is my knowledge of the Silmarillion material.

I could never be a scholar....

....one hopes that they get joy from their different readings. But I have really enjoyed these essays, even though a lot of it goes over my head. What they do for me is give glimpses into elements of story or lore that I would have passed by before now.

As for Beowulf spilling into Tolkien writing LOTR, where for Frodo "the wages of heroism is death".... wonderful.