Mapping Arda, Part III: The Second Age by Anérea, Varda delle Stelle

Posted on 20 November 2024; updated on 7 December 2024

This article is part of the newsletter column Tolkien Fanartics.

Les Cartes ... une grande passion, une invitation au voyage …1

The only Second Age map Tolkien gave us is that of Númenórė, published in Unfinished Tales, so in order to get an idea of how the rest of flat-world Arda appeared during this era, we need to extrapolate from the round-world Middle-earth map and from descriptions in The Silmarillion, Unfinished Tales, and The Fall of Númenor. Fortunately Tolkien’s love of describing landscapes and geographical features ensures there's enough detail from which fans can draw their own ideas, as the following selection of maps of Númenor illustrates.

The island of Númenor

In his visual homage to Tolkien, Jaques Clavreul muses that the unforgettable allure of The Silmarillion, The Lord of the RIngs, and The Hobbit is essentially due to the incredible richness of the universe, with its history, peoples, languages, geography, and above all, a very strong nostalgia linked to the end of a world, the time of dreams.

His colourful map of Númenor is an in-universe result of the deep research by a master cartographer who, unsatisfied with the surviving fragments, reconstructed the map with the aid of lore found with the fragments, thus bringing a little of the past glory of Númenor back to life on paper.

On his website, Jaques writes that

thus, under his pen, the shimmering colours of the fields of Arandor, the land of the king reappeared, as did the golden brown of the Malinorni, the rich pastures of Mittalmar, the white house of Erendis, and above all the Meneltarma, from the top of which one could once see the white tower of Eressëa. The Meneltarma whose summit, it is said, was the only part of the island to pierce the waves after the fall.

But the memory of the road leading to the Tower of Tar-Meneldur Elentirmó is forever lost, like that of Eldalondë the green. No longer does anyone know where exactly the city of Ondosto in the Forostar was located, nor the village of Nindamos in the Siril delta.

Thus, unable to revive memories forgotten by all, the cartographer imagined Númenor as it could have been, as it perhaps was …

Embroidering Númenor

Along with her textile maps of Beleriand and Nargothrond, iaearcanvennamar also embroidered this lovely map of Númenor. With only the black and white Númenórë map from Unfinished Tales as a reference, she chose varying shades of green and brown thread for the land features and graded the blues of the shores until the outer colour matched that of the blue “ocean” of her fleece jacket.

In a personal message, she explained the process of creation:

I embroidered it on a bit of fabric, then cut around it and stitched on the jacket. I had done a coloured pencil drawing a while before that, so I took the colours from it. I guess the technique is needle painting? I drew the outline on the fabric with a water soluble pen, stitched the outline and then filled in the colours. Of all three it’s still my favourite.

Georeferencing Númenor

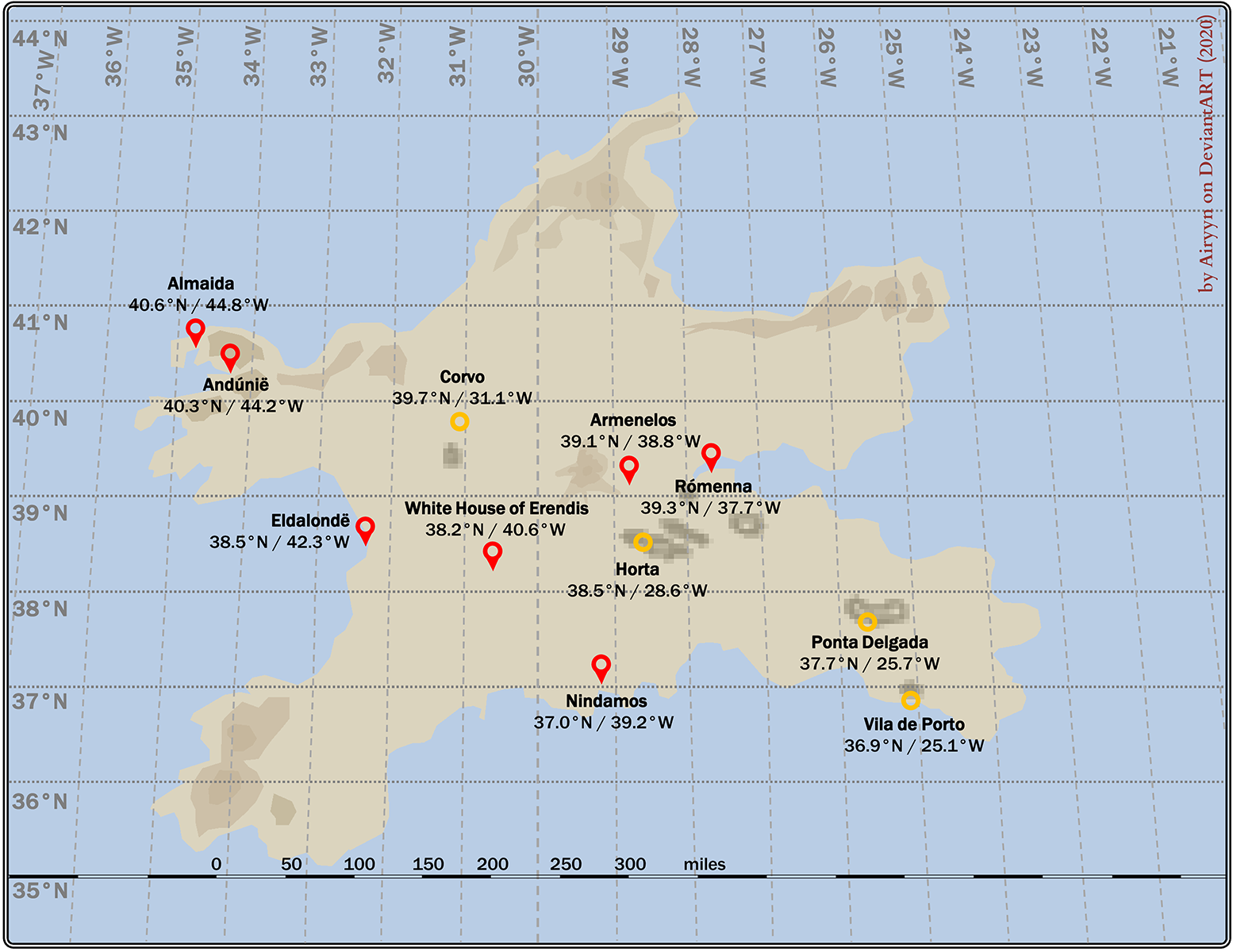

The scale provided with the original map of Númenor makes it easy to deduce the dimensions of the island, which are actually quite considerable, being roughly the same size as Beleriand. Airyyn surmises therefore that the Valar provided more than enough room to accommodate the battered population of Beleriand after the War of Wrath.

Using a combination of known Middle-earth coordinates and real-world vegetation zones, Airyyn deduces that Númenor lies in the region of 40°N (based on the presence of vines on the island) and 30°W (using the proportions shown in the Ambarkanta Map V and placing Númenor halfway between the Bay of Balar and Tol Eressëa). This would therefore place Númenor a little north of the Azores archipelago, a hypothesis favoured by Karen Wynn Fonstad’s Atlas of Middle-earth, where the Meneltarma remains as an unsubmerged part of the Mid-Atlantic Ridge. The Azores are also thought by some to be a vestige of the mythical Atlantis, which makes the location of Númenor close to the Azores all the more attractive.

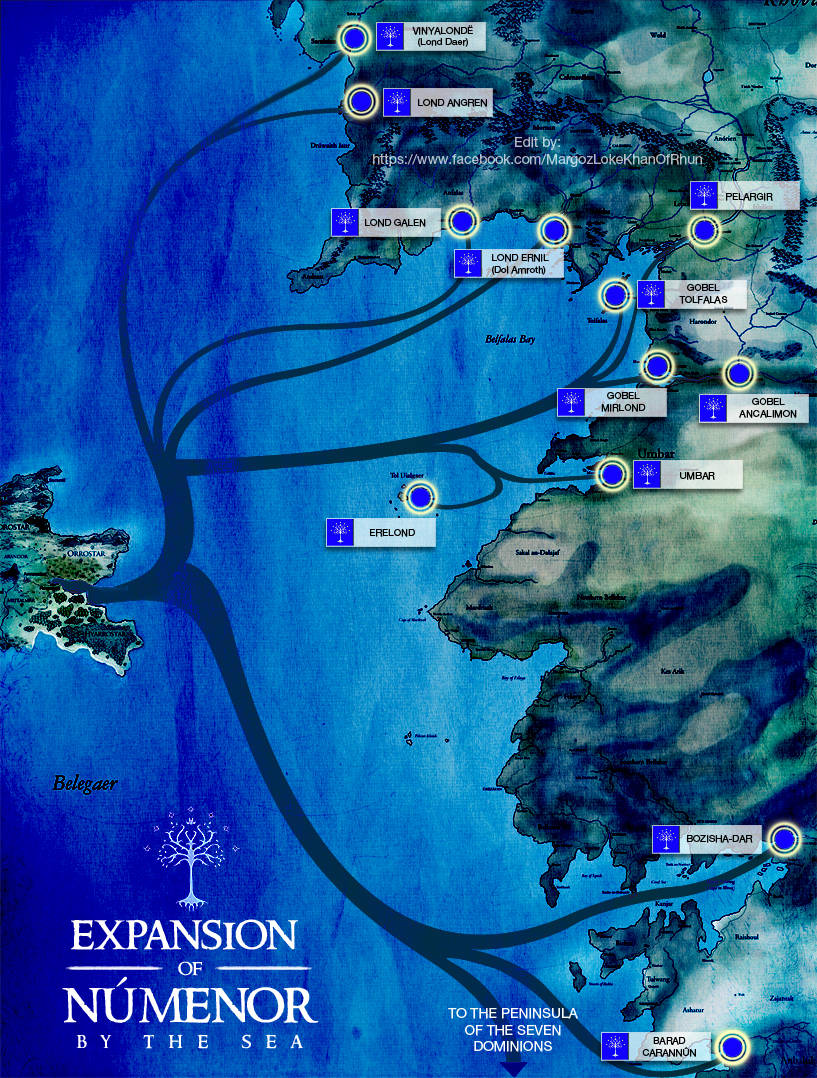

The expansion of Númenor

As they were for so many of us, maps were always kind of a weakness for enanoakd. Encountering MERP (Middle-Earth Roleplay) at the age of eleven, he has always been fascinated by the expansion of the original Middle-earth map into new lands, towns, and cities that still kept as faithful as possible to the world Tolkien created. Later, when he first became a graphic designer, he used his new skills to bring some of this world to life in this map by visualising the sea routes the mariners were likely to take and combining canon port cities founded and settled by the Númenóreans with noncanonical cities in the eastern and southern lands, sourced from the MERP modules and The New Notion Club Archives wiki.

The downfall of Númenor

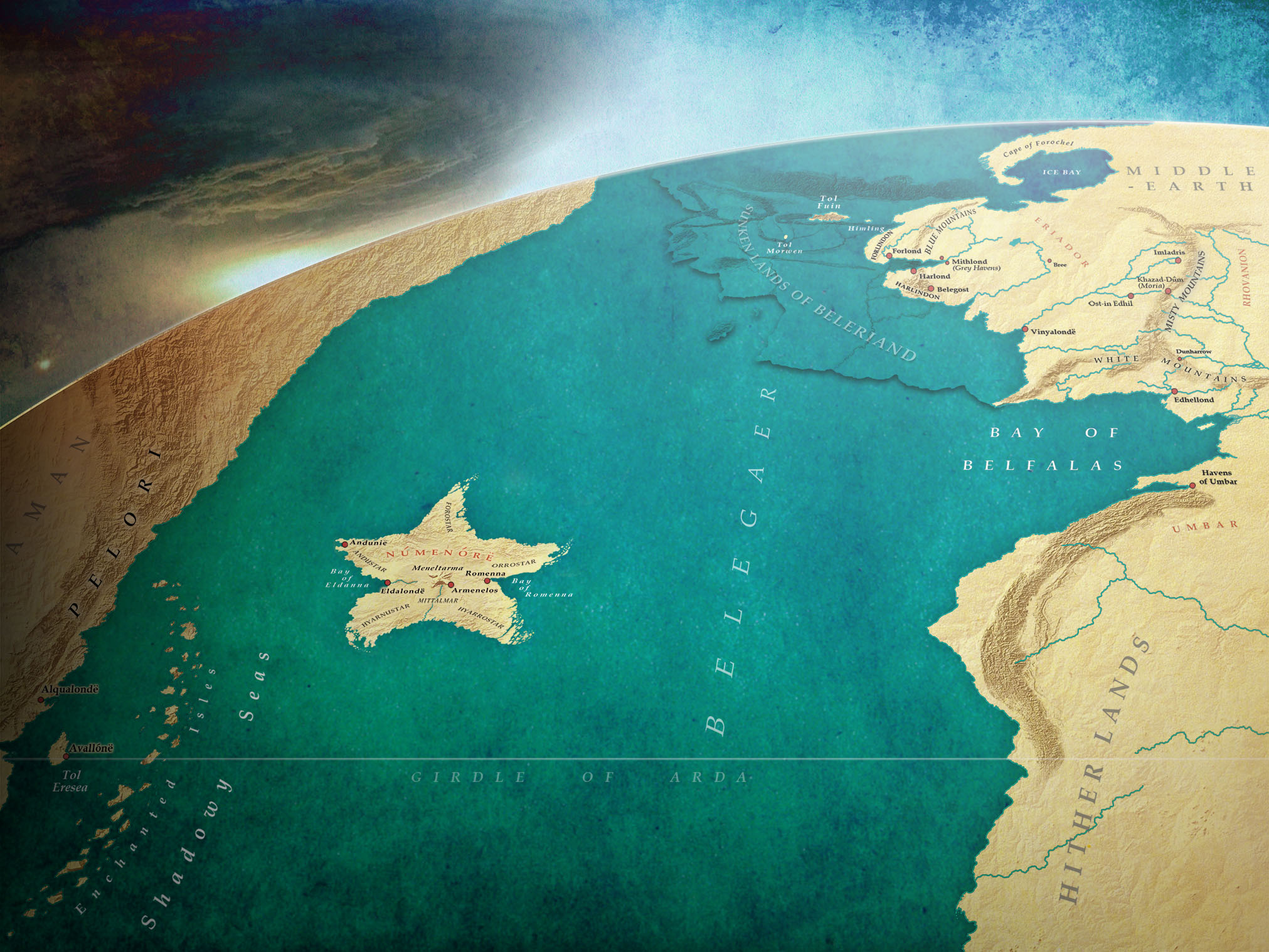

Jamie White is an illustrator who came to specialise in map-making for publishing and TV. In an email to me, Jamie says

The more maps I made though, the more I understood them as images that should combine beauty and utility in equal measure. JRR and Christopher Tolkien’s maps of Middle-Earth and Beleriand are perfect exemplars of this, and could be said to be the most well-known maps in the world – certainly in literature.

The maps I've made are based on those maps, on the early sketched schemes found in the Ambarkanta, on the text when there was no imagery available, and on Karen Wynn Fonstad’s brilliant Atlas of Tolkien’s Middle-Earth. In making them I was extremely concerned with accuracy, and only in the case of my map of Númenor did I diverge from the overall shape of an already established map, which I did for two reasons: to make it more closely match a vision I had of it in my mind’s eye, and to add a small coastal island in the shape of a rabbit, as a personal message to someone.

He locates his map at the height of the Númenorean empire just prior to the Downfall by depicting the storm originating in the West, and also provides context to the Western Isles of Tol Morwen, Tol Fuin, and Himling by including an outline of sunken Beleriand.

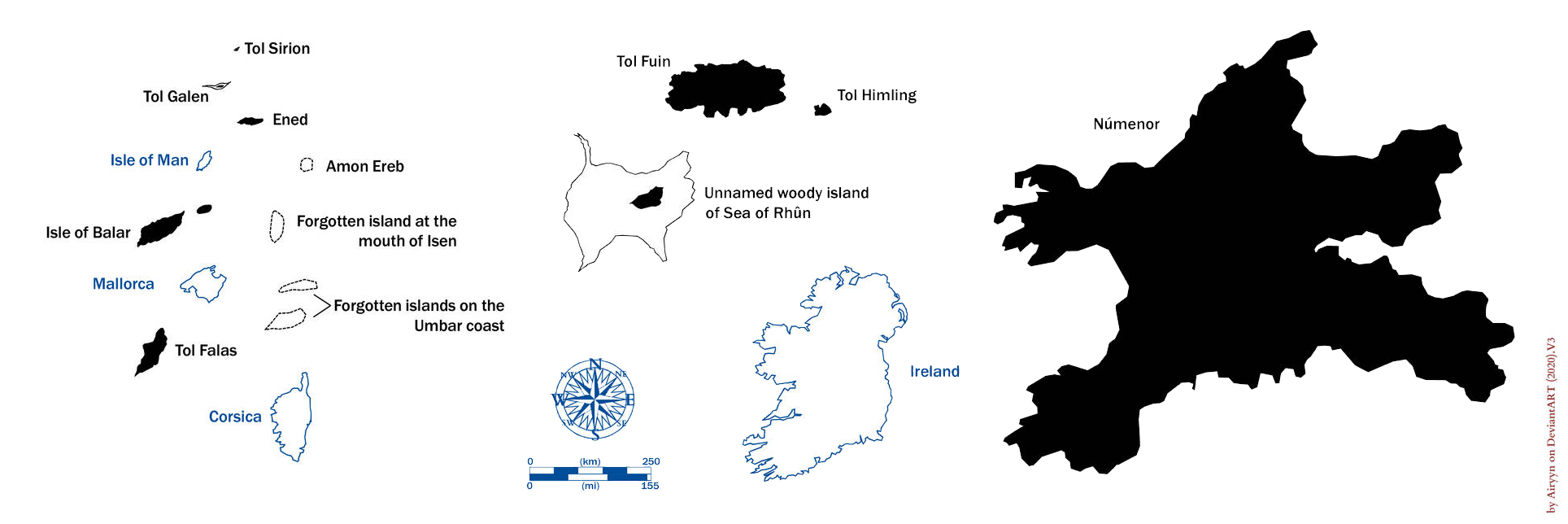

Relative scale of the islands of Middle-earth

By comparing some islands from our primary world, Airyyn provides a visual idea of the size of Middle-earth islands. Númenor is often thought to be too small for a larger population, whereas here one can see that Forostar, Andustar, Hyarnustar, Hyarrostar, and Orrostar are each roughly the size of Ireland.

Tol Morwen and the remnant of Meneltarma have been excluded since their size and shape are unknown. A few “forgotten” islands that appeared only in the drafts of the maps are included: Amon Ereb, a forgotten island at the mouth of Isen, and two forgotten islands on the Umbarian coast. Although the island of Ened in the Firth of Drengist appears on the published map of Beleriand in The Silmarilllion, its name only appears on Tolkien’s original draft called the Second ‘Silmarillion’ Map, which Christopher then reproduced for The War of the Jewels, and is otherwise not mentioned in any of Tolkien's writings about the First Age.

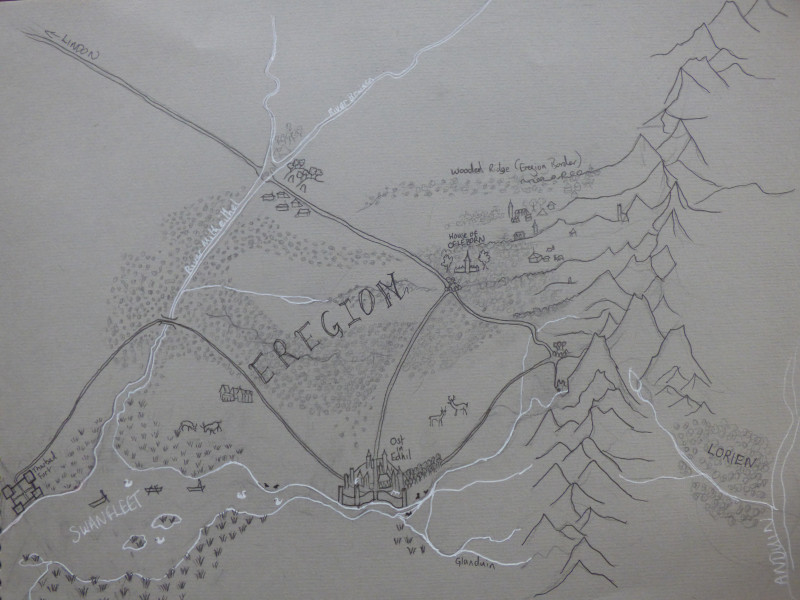

Eregion

In true Tolkienian tradition, Bunn created her map of Eregion, set around 1600 when the Ring was forged, to help with writing her fic Speak Friend and Enter.

Extrapolating information gleaned from both The Silmarillion and The Lord of the Rings, she draws a picture of mid-Second Age Eregion as a largely a wooded landscape, with Númenor’s forest felling not yet extending much beyond the banks of River Gwathlo. The woods would have served as both a source of fuel, bark, and other materials, as well as a hunting ground, while the wide, shallow bogs and marshes lining the banks of the Swanfleet River were a useful food source for the Elves of southern Eregion and the Men of the great woods of Eriador. The relatively newly settled Tharbad was still serving primarily as a fort defending Númenórean timber extraction operations, with the bridge yet to be built. Other settlements were likely to be scattered across northern Eregion through the woods, but no cities of any size: these were homes for Elves to use, particularly in winter. Bunn writes:

I've given Celeborn a house outside Ost-in-Edhil. Given his well-documented distrust of Dwarves, I feel that he probably wouldn't be very comfortable in the city with the greatest friendship ever known between Dwarves and Elves. Also, during the fall of Eregion, Celeborn was present and joined Elrond's rescue force that was swept away into the north, to found Rivendell, and that would be more likely if Celeborn's usual haunts were at the northern end of Eregion. I've drawn his house with two long wings and a tower, and I'm inclined to think that the tower was Galadriel's idea, and was made of stone, but the wings were made of carven wood.

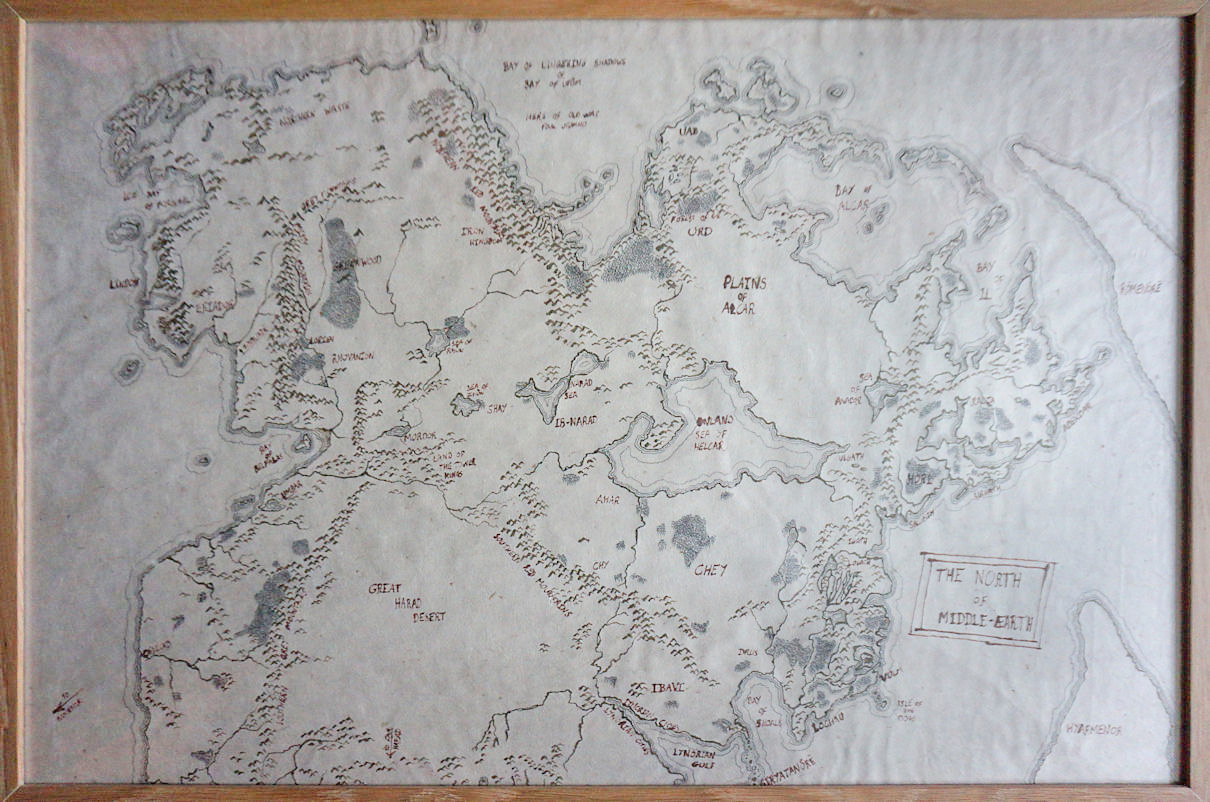

Greater Middle-earth

Using ink on handmade paper and inspired by Pete Fenlon’s MERP (Middle-earth role playing) maps, Mark Poles drew this map of Middle-earth for the Silmarillion tabletop roleplaying game he GM’s (game masters), extending it beyond the canon territories into the far eastern and southern lands. The mountains of Mordor in the middle left provide an idea of scale. The map is set after the fall of Eregion but before the fall of Númenor, so it’s still a flat-world.

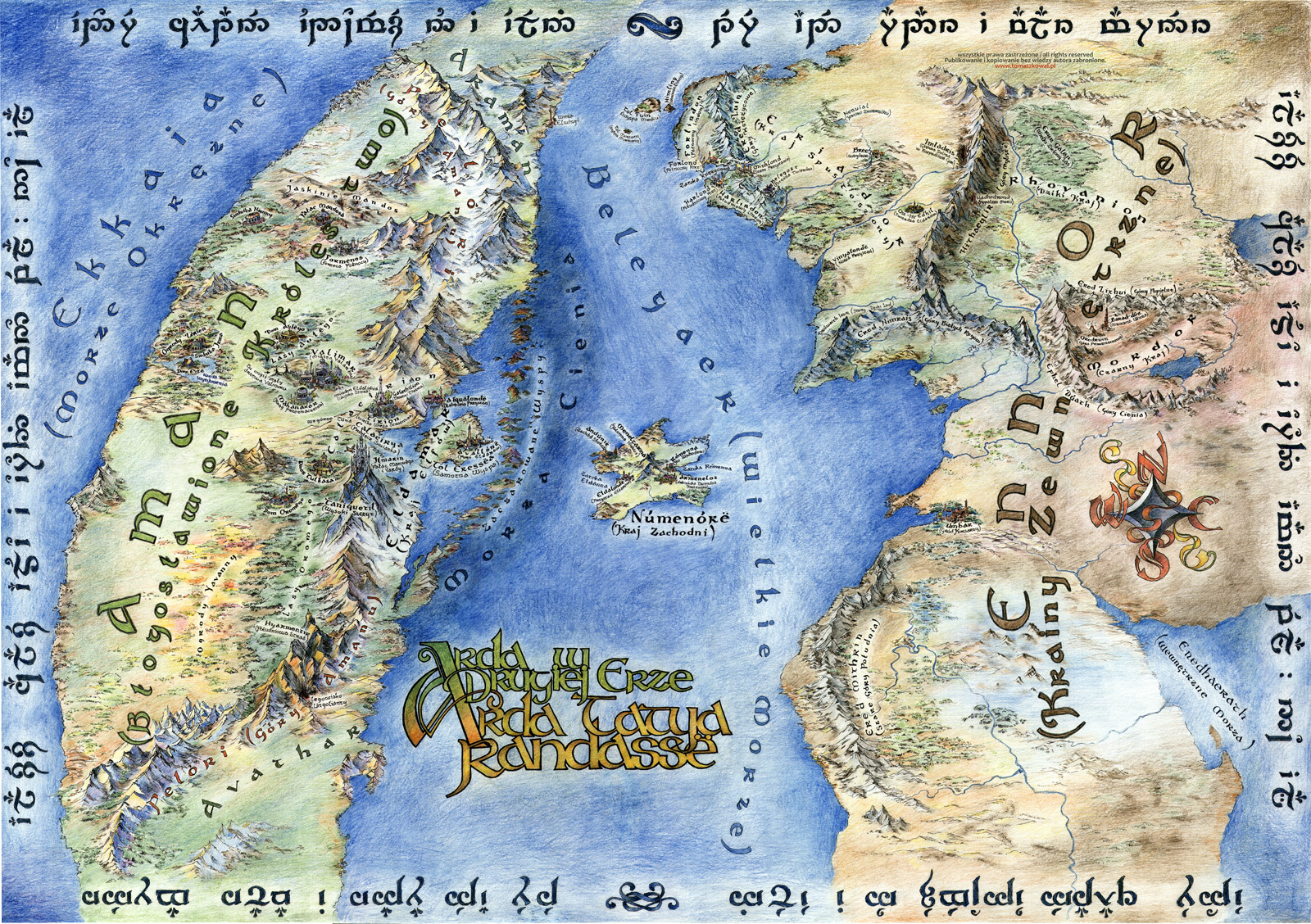

In his part map, part illustration, urban sketch artist Tomaz Koval gives us a vibrant look at Aman, Númenor, and Ennor during the Second Age, with the main features translated into his native Polish as well as Quenya. As with many fan-made maps, his was based Tolkien's descriptions, Karen Wynn Fonstad's maps and Robert Foster's Complete Guide to Middle-earth, along with the help of Tolkienists from the Elendili forum. The Tengwar around the edges is a fragment from The Silmarillion written in Quenya: "For long ages the Valar rejoiced in the light of the Trees beyond the Mountains of Aman, while Middle-earth lay in twilight under the stars".

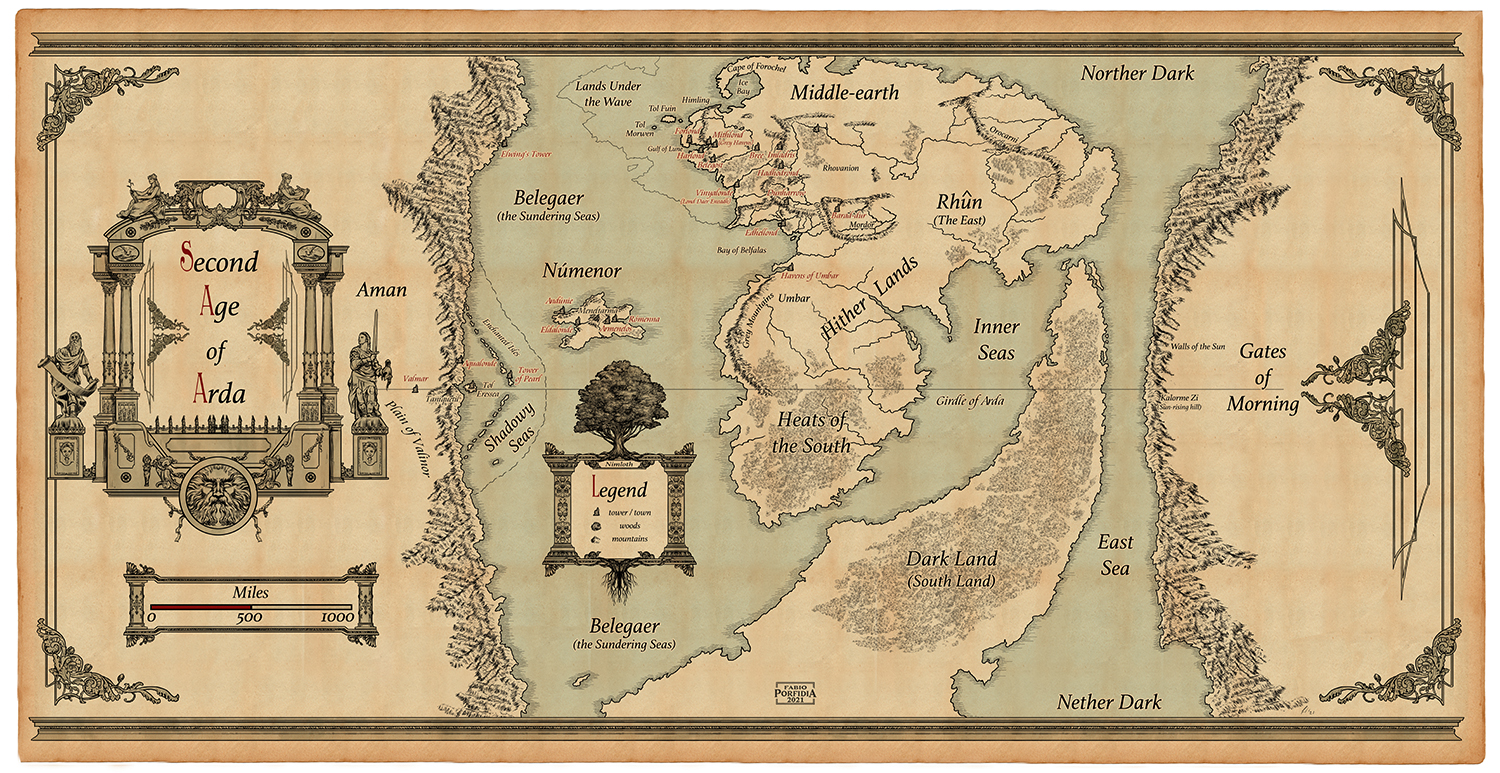

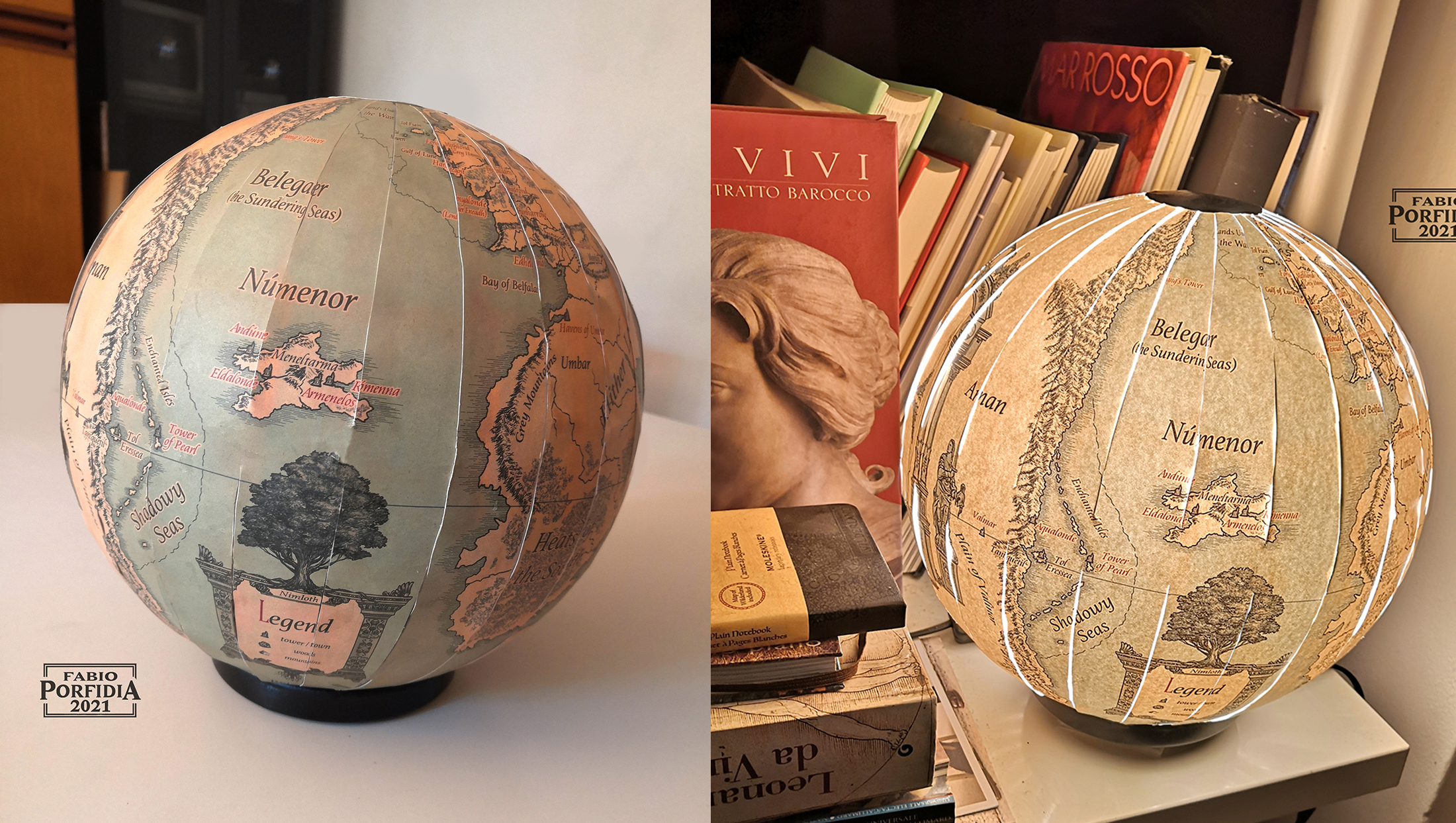

Extrapolating information gleaned from the text of The Silmarillion as well as the Ambarkanta maps, published artist Fabio Porfidia gives us this complete view of Arda during the Second Age, encompassing the banned lands of Aman in the West and all the lands and seas explored by the Númenorean mariners "from the darkness of the North to the heats of the South, and beyond the South to the Nether Darkness; and they came even to the inner seas, and sailed about Middle-earth and glimpsed from their high prows the Gates of Morning in the East."2

Then in imitation of Eru, Fabio made his world round, setting a light (if not the Flame Imperishable) at its heart.

Tolkien scholar and freelance writer and editor Andreas Möhn created some detailed topographical maps of Beleriand and Númenor, drawn to the same scale to show that Númenor is as big as Beleriand. I was not able to make contact with him, but I recommend viewing them on his website, Lalaith's Middle-earth Science Pages, as well as this lovely vintage-style mariner's map of Númenor and the Bay of Belfalas.

Conclusion

Part of the attraction of The L.R. is, I think, due to the glimpses of a large history in the background: an attraction like that of viewing far off an unvisited island, or seeing the towers of a distant city gleaming in a sunlit mist. To go there is to destroy the magic, unless new unattainable vistas are again revealed.3

The same can be said for Tolkien's maps: even though the professor didn't draw any maps of Middle-earth during the Second Age and only the one sketch of Númenor, his descriptions are so vividly detailed, it's almost like he left all these breadcrumbs for future fan artists, cartographers, and lovers of Middle-earth to follow. In this way his universe is always growing, thanks to the creativity and passion of the people who have followed their love for Tolkien's world.

Works Cited

- “Maps... a great passion, an invitation to travel…” quote from Jacques Clavreul.

- The Silmarillion, Akallabêth: The Downfall of Númenor

- The Letters of J.R.R. Tolkien, "Letter 247 To Colonel Worskett, 20 September 1963."

See Mapping Arda Part I: Terraforming and Mapping Arda Part II: Travels through Beleriand

Wonderful maps! Thank you…

Wonderful maps! Thank you for finding and sharing them in this way!

They are lovely, aren't they…

They are lovely, aren't they? Delighted you're enjoying them.

I'm so glad you liked them!…

I'm so glad you liked them! They are amazing!

Another fascinating look at maps....

....especially those where the artists are fleshing out the details from Tolkien's sketches and descriptions of Númenor. I've always felt that maps make the world you are reading about so much more real.

♡

So pleased you appreciate this collection too. I very much agree with you, pouring over the details in maps is such an integral part of some tales, and it's marvellous to have concepts and interpretations from others to explore too.

Oh yes! I agree, a good map…

Oh yes! I agree, a good map makes everything more real, especially with all the work that those artists have put in their map from reading, to collecting all the informations and then, of course, the artistic part! :)

Great work!

Númenor is one of my favourite places in the Tolkien imaginary, so I really loved this wonderful compilation. As an Azorean, Airyyn's overlapped map was my absolute fave and a joy to discover. Thanks so much for putting together this lovely exploration.

I am so glad you liked them!…

I am so glad you liked them! These maps are all amazing! I can imagine the feeling: like finding a thousand gifts under the Christmas tree