Archive Software Upgrade and Downtime on April 19, 2025

Expect site outages on Saturday, April 19, 2025 as we perform a major software update on the archive.

The hunter's heart, the hunter's mouth by Urloth

Chapter 1

Ingwion watched as silver give way to gold slowly from a window and brushed fingers against the buds that opened into nectar dripping gold blossoms hung from the spindly climbing vines of Laurelin. The Two Trees spread themselves everywhere in Aman, roots and vines crawling the length and breadth of Valinor and lighting the land as they crawled and grasped for more space.

There were several chrysalides tucked beneath pulsating leaves, their occupants just beginning the struggle to emerge as the black-blue butterflies that would dance attendance to the golden drape of flowers.

He did not particularly appreciate the golden glow when he could hear his aunt moving around in her rooms already. Fussing and worrying; likely having not slept more than a handful of hours.

It soured any pleasure that could be found in their glow. Though Ingwion was not the sort to spend hours in idolatry of Laurelin and Tyelperion, the light was still pretty to him, and had a tendency to burn away any uncomfortable thoughts.

Between the trees the source of his aunt’s mental distress moved, likely having had less sleep than she. He seemed an unimposing figure; a dark shadow outlined by Laurelin’s growing dominance. Finwë Ñoldoran raised his hand in a gesture of greeting, and caught by the rules of politeness, Ingwion raised his hand back.

Finwë made a gesture, beckoning perhaps. Ingwion considered pretending not to notice and going back inside his rooms. The tragedy that was taking place in both Lórien and Tirion was none of his business, and it struck too close to his own experiences. He did not really wish to keep a grieving widower company, not when the rumours suggested he might have been the driving reason for Queen Þerindë’s complete abandonment of life; hounding her till she gave up rather than give in. Since Finwë had arrived a fortnight earlier, there had been no escape of talk about him either. Usually a fortnight was enough for the gossip and rumour mills to be tired of a single subject, but Noldor Royalty had greater staying power.

There was also his own family’s involvement, so King Finwë was the dominating topic of conversation, driven largely by his aunts and female cousins who seemed to think the Ñoldoran’s continued grieving was somehow evidence of their own bad hostessing. And when that was not the topic, there was the anti-topic of his sole unmarried Aunt, the ironically named Indis, and how everyone was not talking about her shadowing and ability to find a way to be wherever the Ñoldoran was.

The Ñoldoran was of such importance that it had brought his father down from the Mountain, though Ingwë had not really been able to do anything. Occasionally he could be glimpsed from the corner of the eye, whispering prayers as he meandered up and down corridors with a small train of courtiers trailing behind him.

Ingwion looked back into his own rooms, towards the hall that connected family quarters, and yes he could still hear the shuffling of Indis’ pacing and the muffled thump of material as she redressed once again.

Well she would not be ready to linger a few steps behind Finwë for a while yet. He waved again and pointed to the courtyard beneath his own balcony. He would keep the Ñoldoran company until his aunt realised no matter which dress she wore, it would not heal the Ñoldo King’s pain and she best present herself in person.

On the horizon, as he turned away from his window, he could see the crackling rolling storm clouds around the crown of Taniquetil. There was the silver flash of lightning and there was a hint of chill on the breeze that teased his curtains. However he knew from experience that the storm would never reach the Palace. The weather remained tepid no matter the season. His father had chosen the spot well to place his abode here.

Up close, you could not really blame anyone for worrying about Finwë Ñoldoran. He was no longer the ideal of a strong hunter and fighter he had maintained even in Aman. He was hollow eyed and hollow cheeked, his hair was limp and dull, though clean. His clothes hung on him like they were hung on sticks. He had clearly not been eating, and with a father who lost days to his prayers, Ingwion was used to the signs of starving. Had seen how skin yellowed and smelled the wretched sign that someone’s own body had begun to break itself down to survive. He had felt the pinch of hunger himself, until his bones had pushed against his own skin like they were trying to break loose, his head swam, and his teeth had begun to loosen in his gums.

That had never happened in Aman though.

He had been young enough that his footprints leaving the dried, dead lake bed had been far smaller than the ones that had trod onto the glittering white shores. But he had still lived there. He still remembered the darkness, the stars, the times when they were fearful and the times when they had fought one another in bloody fury over resources, and over each other.

Was the Ñoldoran like most of the Minyar who had come from Cuiviénen? Having to live on a carefully constructed diet so his body would tolerate the richer food of Aman without complication? That would explain his decline.

How long ago had Queen Þerindë left to Lórien though? Six months.

That would be enough by any stretch to diminish an adult however healthy. Grief could pull nourishment straight out of food itself it seemed.

Was not Finwë’s own son still a child? Ingwion’s eyebrows furrowed at this thought. Was the young Finwion alright or was he was drained as his father? He had not heard a single world from his aunt about Finwion’s state, though all she spoke of was the Ñoldoran’s grief and subsequent decline.

“How is your son Sire?” he decided to ask, then wondered if he had chosen the wrong topic and found the reason for Finwion’s absence in Indis’ knowledge of all things Ñoldor King, given the degree of Finwë’s flinch. Muscles jumped under the skin and the Ñoldo had a tick in his forehead that began to speed up.

“Finwion?” Finwë asked, and then visibly caught himself, “Curufinwë?” he self-corrected but even that did not satisfy him. He opened his mouth to perhaps use a third name, maybe an epessë. No wait, Queen Míriel had given her child a name also, perhaps it was that one. Then no wonder Finwë was not going to say it.

What a lucky child, the thought was arbitrary and unfair. It was hardly Finwion… or Curufinwë’s fault that Ingwion had remained Ingwion all his life. If his mother had given him a name it had been lost, and he apparently was so indistinct an individual that he had no epessë.

“He is… as well as he can be. I think.” The king’s voice faded away and Ingwion caught the shame at the end of the sentence, half-hearted shame. “He seemed himself when I left.”

Ingwion’s stare must have been disbelieving. The Ñoldoran rallied himself.

“He has been quieter than usual but he is as involved in his studies and in his experimenting as always. I cannot tell any differences in his behaviour. He is a hard child to read.”

Would it not be obvious if he just asked the child instead of guessing? Ingwion bit his tongue since it was hardly his position to comment. Especially not on parenting.

Finwë looked away abruptly.

“He does not know his mother has said she will not return yet,” he admitted with words tumbling out in a rushed confession, for a lesser man Ingwion would have used the words ‘blurted’ because that was what was happening. Kings’ did not blurt things out though.

One sentence turned the conversation from the stilted, awkward talk of near strangers about too sensitive a topic, to something far too raw and intimate.

“Apologies,” Finwë said into the awkward silence, “that was not something I should have shared.”

Ingwion managed a polite enough smile, “some things will out themselves I suppose. In these sorts of circumstances, rare as they are here-” non-existent as they were here, “I suppose it is hard to know what to say and what not to say.”

Finwë’s responding chuckle was reedy, thin, and completely fabricated.

“Ah I shall consider myself tutored then in what not to say at least.”

“Ah no that is not what I meant,” Ingwion realised how Finwë had taken his words, how anyone could have taken his words “I meant-” what had he meant? “-this is new for us all. This is something we have not experienced since the Journey. And here in Taniquetil we are removed from the events in Tirion.”

Finwë nodded.

Ingwion wished Indis would hurry up and chose a dress.

“I had forgotten you were not born here but before the Journey,” Finwë commented lightly and Ingwion, seeing a clear diversion from current topic, allowed him that, though thoughts about Finwion were now pestering him.

“I was quite young when we left,” he agreed, “but I do still remember life before Aman.”

It was a powerful thing to remember. He knew it lingered in their minds, as much as his father liked to pretend that it was all behind them now. As much as Ingwë Ingweron played at being on his way to ascending to a higher state of being, and treated his son like Ingwion had only ever known Aman’s peaceful solemnness, Ingwion willingly recalled, from time to time, the life far less perfect. As a way of finding a thrill. There was nothing in Aman that could quite bring about the feeling of a sickening twist in the stomach, and cause his heart to squeeze painfully.

His eyes flicked to King Finwë, sitting quiet and radiating sadness. He thought of Queen Míriel Þerindë, recalled as sweet and quiet by his family as though her death was a foregone conclusion long before she had laid down in Lórien.

It felt like a betrayal to family and the king, but he remembered still with gut churning glee how Míriel of the Tatyar had appeared with knife in hand at the gates of their village. She had called Indis out and with a few brutal kicks, laid her out on the ground. There had been a murder of crows above their bodies, cawing loudly down at the scene below, perhaps hoping there would be a meal to steal from when Míriel moved away. There Míriel had, with one knee on Indis’ gut and a fist in her throat, whispered words to his aunt that had had Indis shaking and jumping at the shadows afterwards, just as badly as if the Rider had paid them a visit.

He didn’t know to this day what they had been. Indis had never said. Had refused to ever share with anyone.

No one had moved during the entire tableau. Míriel’s knife had been in Indis’ cheek, spilling a river of red down the side of her face. The scar was long faded, invisible now, and perhaps that was why Indis joined in agreeing that quiet, sweet Míriel had seemed very fragile last they had seen her.

When had Ingwion last seen her?

Perhaps a year or two back. She had been wan and disinterested in interacting with anyone. Had constantly reminded Finwë that their son was waiting for them. Really her son had been the only thing she had talked about, when she did talk.

And when had been the last time Ingwion had seen Finwion?

At least a few years before that. And only briefly for he had been a child who had not been able to stand still during formalities and had disappeared as soon as he’d bowed properly, with a hair stroke from the Queen.

There had been a look of adoration as the child had passed by her. A definite connection between mother and child. It had made Ingwion ache. Had he looked at his own mother with such love? How was he to know? His memories of her were few enough. Certainly he’d looked up at her. Most of his memories came from the vantage point of looking up.

Had Queen Míriel really abandoned her son who looked at her like that so easily? Was the news of her refusal being kept from him just in case she did come back?

“If I might ask… why have you not told him yet? This is something that is of intimate concern for him is it not?”

“I have not told him because I do not know how he will react. He is a quiet child but he does feel… deeply.”

“And it would be cruel,” Ingwion hazarded, “to tell him she is not coming back, let him grieve, then have her ret-“

“She will not,” Finwë interrupted, “She is not… she is not coming back. Never. She made that very…” Finwë’s voice snapped and broke, “clear to me.”

Everything in Ingwion crawled backwards. He felt ashamed. He had hurt the Ñoldoran. Finwë was still tall, still broad of shoulder, and when grief ran through his body, his stature meant it was telegraphed more clearly.

“I am sorry,” that was all he could say, “I am sorry Your Highness.”

The gestures of comforting grief were unfamiliar, it had been so long. He awkwardly placed his hand upon one shoulder, felt that was not quite enough, but unwilling to fully embrace the Ñoldoran, slipped his arm to the furthest away shoulder. He was not expecting the sudden weight as the other man tilted his centre of gravity and leant into him.

He had not known that was also being offered but it did not intrude too badly into his personal space. The Ñoldo was not clinging to him and sobbing on his shoulder. Just leaning against him, looking even more exhausted.

“Did you sleep at all sire?”

“I did not but do not suggest I try and find rest now,” Finwë shook his head and looked up at the trees around them.

There was a murder of crows staring back.

Ingwion’s heart tried to jump straight out of his body via his mouth. They had not made a noise, he had not noticed the large black bodies in the trees until Finwë drew attention to them.

He sucked in his breath and it burned on the way down from not breathing in soon enough.

“Did they frighten you?” Finwë asked with a smile more real than the one before. “They have been there most of the mornings I have been here.”

“I did not know,” it unsettled Ingwion. Ravens were not auspicious animals and the Minyar were most concerned with auspices, “if I would have known I could have put out a feeding stand for them. Though I suppose I do not want to encourage them.”

A caw from the trees and then the crows were flapping their wings and making an awful racket.

“Maybe one platter?” Ingwion yelled over the din.

A dismissive ‘wek’ noise.

“I was only being polite, ink-stained turkeys” Ingwion muttered then started away when a deep, sincere, and unfamiliar toll of laughter escaped Finwë. The Ñoldoran covered his mouth with one hand, eyes wide with surprise and apology.

“It is alright,” Ingwion reassured him. The laugh had been surprisingly rough and unpolished and had fit the surroundings like a foot in a glove.

Finwë let his hand drop, smile on his face unlike all the ones before.

“Counterfeit buzzards,” he suggested and Ingwion grinned back. He knew this game. Elemmírë had taught him it.

“Malcontent jackjaws,” and on in that manner, each one of them trying to come up with a more ridiculous name for the birds above their heads using as obscure words as possible. When Elemmírë had played it with Ingwion it had been to force Ingwion to reuse the lists of words Elemmírë had put him to memorising and force Ingwion to expand his vocabulary.

The crows absquatulated by the sixth description, perhaps bored or insulted. They watched them leave, cutting a dark path up to the rapidly blackening storm clouds around Manwë’s manse.

That had been a short bit of fun though, Ingwion found his own malcontent was gone.

“I had forgotten there was a word like fefnicute. I should use it more.”

“Hmm, it was a favourite of Míriel’s, I certainly had it thrown at me often” Finwë’s smile did not diminish to speak of his wife until the end of the sentence. Ingwion hoped it was some kind of progress. Pointed rustling in the trees and then the squeak of the gate as it was pushed open. Finwë nodded to where Indis was now lingering, framed by the artistry that had gone into the ironwork isolating this courtyard. “It seems Indis has arrived to show me the Orangery she promised to. What are your plans for today Prince Ingwion?”

“Mine?” to be honest he had been thinking about escaping the palace for a while, “hunting,” he said quickly because that covered a great deal, “I will be hunting.”

Finwë nodded and his smile was wistful, attention back on Ingwion, “I have not hunted in a great while. I do miss it. Oromë’s favours find you then.”

“Thank you sire,” Ingwion nodded and took a quick leave, brushing past Indis who caught his sleeve then dropped it abruptly. Her eyebrows were scrunched but no questions following him so he took it as an indication to carry on.

He wasn’t sure really what he would do. But he had said hunting. He looked to the spear rack he took some pride in and took one. He had said he would hunt.

He did not return for three days. There was a murder of crows at his back whenever he stopped to rest. He walked with barely a stop, spear unsullied. It was not the best use of his time. He was sure that he could have done something that would have benefited others. Instead three days blurred into one another, endless warmth, light, and walking. And the ever present presence of the crows.

The Palace, which was never a sight he felt any joy or upset upon viewing, was for once welcome.

The crows settled on a tree as he pushed through the small garden gate he used frequently as his escape and when he looked back through the wrought iron bars, they were watching him.

He was accosted or more politely, intercepted by his Aunt Wendë, she of the four daughters, and the perpetually glowing-with-contentment husband, to tell him that the Ñoldoran had been inquiring as to when he might return. She followed this up by suggesting that perhaps Ingwion should wash quickly and pay the Ñoldoran a visit to see what his interest was.

Ingwion did not have time to question how the wishes of a King not their own were such an importance before his Aunt wrinkled her nose and repeated her suggestion that he should wash.

Immediately.

As soon as he put that spear away.

And added her opinion was that he should make use of a well scented soap.

And indicated that he should scrub hard.

Very hard.

Then Ingwion was left alone in the corridor, reeling a little bit at the speed of it, with his Aunt’s silks rustling off into the distance.

Out of misplaced resentment (it was not Finwë’s fault that he held such sway) that Ingwion decided that he would not seek out the Ñoldoran. Itchy with frustrated anger and nothing really to blame it on, he took his sweet time scrubbing himself clean, thoughts of his Aunt and the Ñoldoran slipping from his mind as he doctored to the scratches his feet had acquired. By the time he had soaked the heat right through to his bones, he was swaying with fatigue. At the sight of his bed, the very last thoughts of the stranger in his home and the stranger affect Finwë had on his family slipped away like Ingwion slipped onto the mattress. He pressed his face into a soft, sweet smelling pillow. Darkness began to roll in from the edges of his vision and then a loud and angry caw jolted him right out of the warm and comfortable feeling of nearly-asleep.

And then sleep proper.

He woke up with his face stuck to his pillow and his eyes crusty. He was itchy and his ankles hurt. The bottoms of his feet were painful like they had not been since childhood. The long memory came to him; endless walking underneath stars, spurred on by endless stories from his father who had still been able to speak things other than prayers.

A hand resting on his hair.

However there was no father beside his bed, no hand in his hair, no stories. He rubbed at his eyes and forced himself to stand despite how his feet immediately punished him with needles of pain right up to his ankles.

He shivered. Cold. He had fallen asleep naked and wet from bathing. He dragged on a bedrobe from where it had gone ignored on his armoire.

There was an inquiring croak from his window. A single crow was sitting on the balcony and watching him. It croaked again and though the sight of the animal still raised hairs on his arms, it was a concerned noise to his ears.

Without the will to chase the raven away, he managed a limp hand wave at it.

It did not move.

The tiles of the bathroom were cold and for a moment a relief on his feet before they began to hurt again, this time responding to the chill.

He stumbled through freshening himself up, unsure of whether he should now go greet the Ñoldoran, unsure of a lot of things really, like what time it was and which way was up. It seemed that his sudden need to perform self-flagellation by walking had completely disorientated him which was why he just stared at the aforementioned Ñoldoran when a knock interrupted his shaky procession back to his bed, and the door opened before he could answer it.

“Hail,” Finwë stood and the light of Tyelperion was upon him, highlighting the hollow of his neck, the press of his collarbones too sharply against his skin and yet it made him beautiful, like a statue of hematite he seemed to Ingwion, too lovely, too cold.

“Hail,” Ingwion managed back.

“I came earlier to see you when you returned but found you asleep,” Finwë stepped into the room and the door shut behind him and that seemed a dangerous thing to Ingwion yet he gestured for the king to take a seat upon the plush long chairs of his receiving room, aware of the yawning mouth of his bedroom door behind him and the mess there of cushions and sheets and blankets strewn all over by his restless sleep.

Had Finwë simply lingered in his sitting room until it was clear Ingwion was not present or a servant intervened? Or had he opened the heavy door and stepped through onto the rug covered tiles, walked past the wall of windows Ingwë had commissioned so that Ingwion never needed to fear sleeping in the shadows again, and come up to the bed?

Had he stroked Ingwion’s hair in an echo of a touch Ingwë had forgotten how to give?

“Was it good hunting?” Finwë asked him.

“No, I am afraid it was not.”

“That is a great pity,” Finwë looked sympathetic to Ingwion’s plight though Ingwion realised he did not have a plight. He had not really wanted to hunt. He had simply wanted to leave the house.

“Your aunt did mention to me that you prefer the endurance hunt, is that why you were gone for so long? It was refreshing when she and your father even began to debate the different styles of hunting. She is so renown for her running now that I was surprised to learn she prefers stalking and waiting out her prey.”

“All hunters prefer their own methods, she was an effective hunter once Sire,” Ingwion demurred but his stomach gave an envious sour twinge. His father had managed to talk about something than holy powers? Had managed to debate rather than chant? Had … Ingwion swallowed back bitter bile. His father was still human. He must not think of his father as inhuman.

“As many of us were,” Finwë smiled at him, “it was a necessary skill for life. I did not think to enjoy it. What is it you enjoy about it Ingwion?”

Yes, what was it that he enjoyed about hunting? Certainly the taking of an animal’s life was not the draw for it meant the hunt was over. Ingwion did not like preparing the animals be brought down and treated it as a necessity, though it gave him a sense of accomplishment.

“I suppose it is because it is an acceptable pursuit for me to have that takes me beyond the palace,” he answered and wondered how this older, established king who was as chained to his throne as Ingwë was to the dais on Taniquetil, would respond to his selfish plight, “and does not involve anything to do with the affairs of state at all. Or at least that is what my ideal hunting is.”

“Young up and coming sons of lords seem to show up to ruin your escape do they?” Finwë’s smile was indulgent which was perhaps the least of the worst Ingwion could have expected but his voice was warmer than he’d hoped for and not disinterested.

Ingwion laughed, nervous that Finwë had realised his common gripe so quickly.

“Yes,” he admitted, “often if I announce I am hunting it is suddenly an affair with horses and tents and a multitude of companions, and their companions, and their servants.”

“Hence your abrupt departure,” Finwë nodded his understanding, “would you tell me of the prey you prefer to seek? What are the conditions like so close to the mountains?”

Ingwion was happy to tell him, falling into the self-gratification of talking about something he knew quite a bit about although it seemed at times he was preaching to the choir yet Finwë still remained bright eyed and more alert than Ingwion had seen him in conversation his entire visit.

It was only encouragement to keep talking, and with some difficulty but great pleasure when at last Finwë gave, Ingwion drew from the Ñoldoran a few tales of particularly harrowing hunts from the days before Ingwion’s birth. It was a tricky and difficult matter to restart their good humour and cheer when inevitably this story would glance upon Queen Míriel who had been a prominent hunter herself.

Yet Ingwion found himself growing resentful of when Finwë would stop and pause because it seemed to him a shame to not tell these stories. All his recent memories of Míriel were of such diminishment that he craved to know more about the woman he had seen terrify his aunt into compliance.

Finwë gave out slivers at first, miserly keeping the best stories to himself until a servant came and went and came back with a platter of bread, fruit, and cheese, but more importantly a thick red wine that went down well.

They sat, knee to knee, and then at Finwë’s insistence that if he was just woken up Ingwion needed more food, they asked and received a cold small roasted quail that must have been left over from his aunt’s breakfasts.

They drank. They ate. Finwë was right, the quail was soon picked to the bone. It had been a small bird it was true but the rest of the platter had been generous and Ingwion was responsible for most of its decimation.

Finwë refilled his glass then Ingwion refilled his glass, then they refilled each other’s glasses, Ingwion called for another bottle of the same. They laughed over the foibles of court life in both of their homes. Compared the latest styles of court dress and chuckling agreed none of the chiffons or the silks were suited for hunting. At last Finwë’s shoulders lost their rigid propriety, his eyebrows lost their tiny, permanent furrow, and the tales began to flow.

Finwë caught Ingwion in a web of dark shadows and racing heart beats; each step possibly your last but the desperation and hunger giving no quarter. Onwards, onwards, onwards and the monsters were waiting for you in the trees where you thought to hide and by your snares, your kill a bloody smear across wretched, shattered mouths.

One bottle of wine had become two had become three.

Míriel Þerindë was no trembling invalid; no shadow against the wall. She was a wrath in the darkness, a howl of rage against the conditions they had to live in. She clawed and bit at life and held it in place when it would have fled. She climbed trees towards gleaming cruel eyes with her own eyes filled with death.

Fourth bottle and Ingwion’s head was swimming with more life then he had felt in centuries and they were leaning against each other’s shoulder, the platter decimated.

“You have read Rúmil’s latest offerings?” Finwë’s head lolled.

“Have I! Elemmírë was frothing over it so much that he brought it to court to petition Father formally reprimand Rúmil for… for…” what had Elemmírë been yelling about. He was a beautiful man Elemmírë, but he did go on and on and on until your ears rang, “his ‘flagrant shamanistic leanings and pagan propaganda.’”

Finwë roared with laughed. His hand squeezed Ingwion’s hip. Ingwion slumped over into the warm support of his side, grinning himself.

“Would that those two finally meet in person,” Finwë took Ingwion’s weight and simply leant back onto the arm of the chair, still kneading Ingwion’s hip under his hand, “and sort out this unspoken violence between them but I would miss Rúmil’s prissiness when Elemmírë delivers another psalm. He calls him the wretched bumbling monk.”

Ingwë felt far too amused and shook his head.

“They’ll never agree.”

“They won’t…they won’t. Oh but I know that Rúmil wrote that poem deliberately to incite Elemmírë because he came to me before its publication for a promise of protection.”

“So all of that about tasting the echoes of the lake in the breath of the young was entirely to annoy Elemmírë?!”

“Oh no I believe he was sincere in many of his imageries, Rúmil is too much an artist to defile his own work for pettiness sake; he is not simply a scholar.”

“I am relieved,” Ingwion confessed with happy giddiness, “I did enjoy that poem.”

“I think I can taste it,” Finwë recited, voice rumbling against Ingwion’s chest as he rearranged them to lie side by side against the arm of the chair “the trees and the spaces between the trees; the places where the trees are not, all filled with starlight and endless freedom. You carry it around in your heart until it has invaded your blood and even perfumed your breath.”

It was uncommonly poetic for a Ñoldor. Rúmil Lambengolmo really was a treasure of his people. Ingwion swayed. The wine heavy, eyes heavy, ready to fall and allow Finwë to be a heavy weight on his body. He liked it as it was now, with the chair holding him half upright.

Finwë pressed his mouth in gentle caresses against his forehead then to his cheek. His hair was cool where it pooled against Ingwion’s neck and he raised his hands to gather it up and run his fingers through, resting finger tips on the warm strong neck and then more boldly his palms.

Finwë smiled against his jaw and let their mouths meet at last; a soft chaste press that Ingwion pursued. If he kissed enough would he taste the dark shadows Finwë had avoided and Míriel had hunted. The shadows that had swallowed his mother and beyond that the stars that Laurelin and Tyelperion drowned out were carried on Finwë’s breath.

Ingwion grasped at them, clasped Finwë to him, felt the ties of his bedrobe being undone and warm hands were touching him.

It did not matter, the world did not matter, all that mattered was the wildness that revealed itself in Finwë’s every move.

A thigh between his and he parted them. A hand seeking there and he gave.

The frame of the chair was groaning from the stress on its joints. A rhythmic soft creak.

Finwë rose above him, blocked the light, skin flushed and eyes filled with astral glow. He moved and Ingwion broke apart with razor sharp delight, gripped Finwë’s hips tighter with his thighs and prayed to Eru and whatever lay beyond the Almighty-in-repose that he be here again; that this felicity find him again.

If his father could have had joy like this would he have still abandoned the world and Ingwion within it?

Finwë kissed this thought away and dashed all others with growl and a tightening of his hand which clasped engorged flesh.

Felled, Ingwion let the pleasure carry him away as rightful trophy.

It lay him down in his own bed and let him wake filled with sweet satiation and Finwë supine beside him pressing kisses lazily to his mouth, their hands caught together between their bodies while Tyelperion’s silver made the gold ring Ingwion ran his fingers across glint each time they moved.

Ingwion felt a pang of guilt, vague guilt, but more than that strange kinship.

No wonder.

A strong small foot that had viciously taken out his aunt’s ankles and the knife that sunk into the pale vulnerable flesh of Indis’ cheek.

And no wonder his aunt lingered like a talkative shadow at Finwë’s ankles.

Had he unwittingly stepped in a trap? Did he care? No.

Some holy law was surely violated by this.

They fell together again, lightning from the divine seat above the palace failed to strike them, and Ingwion took his turn to rise above Finwë, devouring the sight of him against the sheets; dark hair and kiss red mouth and hands reaching up to him like the court congregation reached to Ingwë.

In mingling they rose and washed together, lost more time to appreciation of each other and then Finwë knelt to doctor Ingwion’s bruised scraped feet; carried him to the courtyard and they sat in the shadows cast by the intricate gates of black wrought iron that pretended to be a fall of wisteria blossoms.

Ingwion had learned to play the harp here; learned to read and write; all of the things that were now taught to children and not confused young men. And thoughts like these lead their conversations cyclical; once more Ingwion hurt Finwë by asking him of his son; The High Prince of Tirion… the only Prince of Tirion. This time Ingwion urged the Ñoldoran to go to his son and tell him of Þerindë’s decision.

Comfort him through the grief.

“You are the only one to tell me this you know,” Finwë tapped his fingers against the bench, “both your aunts and your father are of the opinion that Finwion should not be told about this. He is too young to understand death yet.”

Ingwion had been feeling heavy handed and presumptuous for trying to order the Ñoldoran as though their coupling had given him some kind of power or equalled their status.

“Then what are you going to tell him when he next asks you when she will return then? And when will you tell him the truth?” Ingwion asked him, frustrated at this. How stupid. He had lived that, the constant uncertainty of when his mother would return and wondering where she had gone. How everything inside him had crumped up to learn she had died, years earlier. Having to grieve raw and fresh when all the adults around him had had time to go numb had felt so unfair and frustrating, and had made him feel ashamed to display open grief.

Would Finwion one day feel the heavy mourning for his father’s loss of touch? Was he already wondering at his father’s withdrawal?

Finwë had never spent so much time away from his family until Míriel had departed. Surely Finwion was alone and wondering why, or possibly what he had done to be left alone.

Ingwion knew this certainly, because he had thought those things before too.

It hardened him to the rightness of his decision.

“I will go for you,” he repeated, “Sire your son needs succour. You should ride with me also.”

“I cannot,” Finwë shook his head. Ingwion repeated his plea after the next mingling once they had loved and disappeared to explore the water gardens in progress alongside the road and was refused. He tried again when they had spent that whole next mingling in each other’s arms, not just mingling but with a great pile of Elemmírë and Rúmil’s works between them, tracing the rise of the great feud. Again refusal.

“But go,” Finwë said the third time he asked, “please go because you care about him without meeting him. I wound you with my refusal but I wound myself either way I choose. If you need permissions then this is it, Prince Ingwion please I beg you, go to my city Tirion upon the hill of Tuna, and make sure my son is hale and whole.”

The arrow of disappointment was still in Ingwion’s heart when he dismounted beneath the shadow of Mindon Eldaliéva and walked into the echoing dark shadows Finwë called home. The crows followed him and settled around on the courtyard walls.

There was a dearth of servants. He walked long enough to become confused before he saw a single maid who looked put out to lead him to a great conservatory where she assured him the Prince would likely be.

Likely.

The room was filled with glass terrariums where reptilian occupants blinked at him, and a tall cage in which a flock of finches were gossiping amongst themselves. There were wild animals, stuffed and displayed upon false terrains, snarling or crouched; mockeries of the beauty of nature.

“Who are you and why are you here?”

I have come to do what your father is too much of a selfish coward to do, Ingwion thought resentfully, then pushed those thoughts hurriedly out of his mind and bowed to bring himself to the height of the child who had stepped out amongst two piles of books the height of Ingwion’s shoulder.

He was… so small. Ingwion was shocked. He shouldn’t have been. He had attended the feast in celebration of Finwion’s birth, but with every new missive regarding the amazing achievements of High Prince of the Ñoldor, that his mind had rewritten his expectation so that he had thought he would meet a youth on the verge of adulthood. But Finwion was… so very small. The top of his head barely made it past Ingwion’s hip.

Suddenly very unsure of this entire thing Ingwion knelt so their eyes were at a more equal level.

Finwion had a piercing gaze, eyes silver-grey surrounded by dark lashes that, given the general sexlessness of a child’s face, made him seem girlish, or should have. Instead it just drew attention to the fact that the child barely blinked at all.

“I have come with bad news,” he tried to make his voice soothing and sympathetic, “would you like to sit down?”

“No I am well,” the child refused bluntly.

Ingwion drew in a breath. He was uncertain about all of this. It had not seemed right before he’d left but now it felt absolutely unnatural.

But the Ñoldoran was not going to tell his son. The Ñoldoran was running scared from his own child.

“Very well,” he sucked in another breath, “news has been received that your mother has refused to return to her body-“

“I know that,” Finwion’s voice was impatient, “she is still unwell. She cannot return until she is healthy again.”

“No,” Ingwion bit his tongue to stop himself from snapping and forced his voice down, “she has said she will never return. She says she will not return back to life. She wishes to stay in Mandos indefinitely.”

Finwion went… very still. Ingwion could not even see him drawing breath. He looked like the porcelain dolls the Telerin liked making. Ingwion’s skin crawled.

“You are mistaken,” the child said at last, each word very precise.

“I am not,” Ingwion’s crawling skin abruptly tightened.

“How do you even know?” Finwion stridently insisted. The floor vibrated gently beneath Ingwion’s knees.

“Because I heard so from your father.”

If Finwion had been still before, he was lifeless now.

“Who did he hear such from?” the child whispered, for the first time something other than impatient, for the first time sounding like his actual age.

“Your mother,” Ingwion braced himself for the impact of those words, ready to embrace the child if he needed to cry, but he was not expecting what came next.

Finwion’s face crumped… and all the glass in the room exploded at once.

“No!” the child shrieked, painful and broken, and fled from him, through a room that suddenly trembled and convulsed like a living thing, the marble and plaster cracking.

All instincts said to run. Run away and not look back. Ingwion felt his stomach turning to water and his skin prickle so bad it felt like it was tearing, as he tried to keep his balance, and ran after Finwion.

He ran through a menagerie of glass containers, all exploded. Preserved lizards and pinned butterflies had been dashed against the wall, and there was the vinegar stink of the preservation fluid that had held the moist frogs littering the floor that he had to step around. A large container was completely ruined and its living contents were slithering between the glass on the floor like diamond pattered eddies.

Who let a child keep snakes? Ingwion jumped over the golden winding coils of a Valmar Asp, and broke into a run, down a long amber embedded corridor, the expensive tree effluvia untouched save a couple of tiles of it fallen down.

Finwion might have been small but he was fast. Ingwion only had which doors were opened to try and hunt him down, and the increased vibrations along the floor. One room was an empty, barren looking nursery with half packed boxes around it, and a nest of blankets and pillows on the floor next to the tiny, dismantled crib of pearl and silver he remembered Olwë gifting.

There was nowhere for Finwion to be hiding there. Ingwion backed out and turned around. The next room was clearly the Ñoldoran’s. The bed was messy and unmade, the blankets and pillows pulled off it and missing. Given the colour scheme of the room, they had gone into the nest in the nursery.

Another room was a child’s room but it was unlived in. It looked too neat, and the bed wasn’t so much made as set in stone, the corners sharp and every line of it parallel and stiff. Did the servants even come down here?

Another shudder and he rest his hands on the door frame and it came away with fine coating of dust.

No they did not.

The last opened door greeted him by nearly slamming into his face as the strong vibrations swung the door into him.

He shouldered past it and promptly slammed himself back against it as he nearly stepped into a void of stars.

Heart racing he got his bearings and realised it was a tapestry hung over some kind of rack. He stepped past it then threw himself back again at the tidal wave of flowers that loomed over him. There were too many to name them all, and this tapestry had been hung from the ceiling so it curved overhead down to the floor. Around it he stepped again, and nearly jumped out of his skin to see his father staring back at him thoughtfully… though Ingwë’s lower body devolved into hanging threads, the portrait unfinished.

Yet more unfinished tapestries were everywhere, hanging over chairs and over racks, portraits, scenery, and scenes that could only have come from the Þerindë’s imaginings, some light, but many of them darkening towards the bottom; light hearted narratives fragmenting into disjointed dark endings.

“Ammë!” a child’s voice wailed from behind the wall of cloth.

A breath away from turning back Ingwion cursed and followed through, tracking Finwion’s screams for his mother through the endless room of tapestries.

“Ammë! Ammë! Ammë!”

The voice moved about in front of him. The ground continued to roll and buckle but here the windows were not shattered. The walls vibrated and pulsed and the plaster cracked but when it fell it slowed before it could touch the vibrant cloth everywhere, and altered direction so it would not stain or ruin.

At last, somewhere close beside Ingwion, there was the thump of a body falling on cloth and the wails turned into a long sobbing moan then turned into sobs proper.

The shuddering began to decrease in severity.

Ingwion had come to the centre of the tapestries. There was a large skylight above, allowing light to stream straight down onto the warm, comfortable area. There was a spinning wheel, many types of looms, square and round embroidery hoops and all manner of strange wooden devices he was sure were for use in embroidery. There were great piles of unsullied cloths, and racks and boxes of threads in all weights and materials. In this treasure pile lay Finwion, limp with exhaustion but with the energy to sob hard enough that it sounded nearly like the child was vomiting.

Ingwion had sweated through his clothes, his tunic was soaked right through. He realised this as he knelt down beside Finwion who offered no protest when Ingwion turned him on his side, then seeing the wretched face before him, wrapped Finwion in the cloth beneath him and picked him up.

He sat in one of the large chairs, tried to ignore how he was leaning against an unfinished blanket of irreplaceable beauty, and probably ruining it with his sweat.

He did not have to wait for long. Grief and rage and exhaustion were a sophoric mixture. Finwion was asleep after not too long, and Ingwion, unwilling to make his way back through the maze of tapestries just yet, let himself doze through the encroaching mingling.

Finwion woke him with a soft cry, sobbing into his small hands and curling up small and tight into his arms.

“I am here,” he told him but realised it would not be much of a reassurance because Finwion had only met him hours ago, “I am here Curufinwë Finwion.”

“I know. I do not want to be called that name. My name is Fëanáro.” Finwion sniffed and wiped his nose on his sleeve. Ingwion noticed that the little prince was clean and well-dressed but the buttons were not done up right and many of the ties at the back where he might need help were not done up. With a closer look he realised the child was wearing two smocks and the bottom one was dirtier than the first though the cuffs were unevenly clean and had water stains.

Hot anger, missing when it should have been present, finally introduced itself. Where were the servants? The nursemaids? Where were the companions? The tutors? The other children of nobility and their minders?

The children of nobles who deigned to ruin Ingwion’s hunts had educated Ingwion on what a young child of nobility was entitled to.

What a childhood in Aman should entail for those who were socially upward and Finwion was a prince. This was not something that could be explained away as the difference between Minyar and Tatyar.

He knew that Finwë, in spite of his cowardice, loved his son.

He must love his son, if his love was so great for Míriel that it hollowed him then he must love the child she’d given him.

This resembled too much how Ingwion had been left once the bones of Tirion had been built, watching his father who literally set himself apart from the world in the prayer chamber at the top of Mindon Eldaliéva, eyes set upon the ocean so he would see when his most precious friends at last crossed over. But Ingwion had been a grown man. Naïve and uneducated from his childhood on the march; old enough to understand and take care of himself with few mishaps.

Finwion was young. Finwion was an infant whose crib was only now being disassembled.

“I shall take you back to the Palace of my Father,” he gentled his voice, “in the foothills of Taniquetil. Your father is there and wishes you were with him.”

It was a lie. Finwë had not said anything of the like and the way he was clearly running away belied a wish to see his only child.

There was a wound in his heart. Ingwion felt it tear; tear up his eyes and drench his mind in dark resignation and despair. Belatedly he realised the wound had been there an achingly long time and by forcibly involving himself in this he was reopening it. Or widening it.

“I do not want to go there,” Finwion, but Ingwion supposed he should call him Fëanáro though such a name seemed too much yet for someone so young, “I do not want to go there because Father went there because it is easier to forget there. I heard him say that. I do not want to forget! Not her!”

Ingwion rocked him and was aware so keenly of how fragile Fëanáro’s hands were as they fisted into his shirt. They were strong but the fingers were so fine and delicate they seemed crafted rather than grown.

What a little brat he had been upon first meeting. Typical of a child who needed to build walls and walls around himself. Thinking of how he himself would just up and leave the court with no dues to any celebrations or politeness had him seeing parallels.

What had he wanted when he had first come to these gold and silver lands of domestic joy?

His mother. His father.

Impossible. Impossible.

His aunts too busy with their own families.

Indis away running through the hills and singing gay songs; surrounded by a chorus of adoring maiar.

He alone holding one of the spears they had used to survive. Walking away from the building sites he roughed his hands on when he was told the son of their new ruler should not concern himself there and continuing to walk until Maia Olórin had been dispatched to retrieve him and chastised him when they found him skinning some strange bearcat creature.

He had been confused and half wild. It had been comforting to look after himself here in the forest where the gloom could pass for twilight, and forget the city existed at all. The Tatyar had arrived while he had wandered. His father had only thought to find him once the new city in Valmar was underway.

He did not care to go back.

Maia Olórin had not argued but had not left him be. They had simply companioned him in the fana of a Vanyar hunter, tall and strong, until he could bear walking into Valmar of his own volition.

“Fëanáro,” he asked gently, thinking of the room where the bed was all sharp points and the door way had dust on it and the nest of Finwë’s blankets in a cold and emptied nursery, “is there someone I can take you to? Someone who can look after you and make you feel safe?”

Fëanáro face had turned mulish when he began speaking but the word safe had his expression crumbling like sand before a wave and he buried his face forward in Ingwion’s shoulder and just nodded before mumbling a name.

Ingwion found him some clothes, clean ones; bright ones; ones that fit, and let him pack a little bag of toys, a woven rug from Finwë’s floor, and his favourite books before he picked him up again and walked through the empty hall of the palace. Servants should have hastened to them, should have been crowding around in fear and worry for their prince. At the very least should have paused in their work in confusion and should have asked where their prince was being taken, yet were absent to do any of that, and departed the palace complex.

The anger that had joined him in waking took note of this. It also made note of the servant the day before.

The crows were still there. Unruffled. Thankfully silent as they began to follow Ingwion through the city at Fëanáro's directions. The city was in shambles. People were gathered on the streets, crying and pointing to the damage done to their houses and livelihoods but it seemed no one had been injured or killed.

“Have you eaten recently?” he dared to brush hair away from Fëanáro’s face and was allowed the intimate gesture. The child had to think about it, then tentatively opined that he might have but he did not remember.

The earthquake had not touched the tree bowered part of the city Fëanáro eventually lead him through to reach a handsome house made of dark wood and gold stone. Rúmil Lambengolmo was not the man Ingwion expected to meet when he thought of the creator of the written word and the so upheld and so called superior Ñoldoran answer to Elemmírë the Word Smith.

He was beautiful the way that lightning striking the earth was beautiful; the light of stars upon his brow and in his eyes wisdom and knowledge had polished his fea jewel bright. He answered the door personally, the guest hall beyond bright with tapestries and the laughter of students and friends.

He didn’t seem the sort who deliberately wrote breath-taking poetry to wreck his rival’s day.

He seemed more the sort Elemmírë wrote poetry about.

But any worry and any doubt Ingwion had was relieved when that implacable face gave way to soft understanding and regret followed by protectiveness when Ingwion explained, slightly tongue-tied, and Fëanáro cemented this by going into Rúmil’s held out arms without a single peep of protest, burrowing into the Lore Master’s embrace even more frantically then he had Ingwion’s.

They exchanged very few words, but Ingwion left assured that Fëanáro was in the only hands who could currently hold him and not break him.

And the rage that had begun when the littler prince had woken up blossomed into a beautiful flower on the ride back to Taniquetil along with his entourage of corvids.

He found no satisfaction for it though because Finwë was nowhere to be found; the courtyards and the garden and Indis said accusingly “I would have thought you would know where he was… where have you been this past week?”

He escaped her to his rooms, watched the crows disperse into the mingling after he had a servant lay out a tray of treats for them, and turned to his bed seething. Finwë woke him from uncomfortable dreams with a kiss and Ingwion’s clothing already half scattered. He buried his head between Ingwion’s legs before he could say a word, and did not let him speak until Finwë lacked the strength to silence him.

And then Ingwion raged. Raged at his abandonment of a child so young. Raged at the servants who had abandoned that child also. Simply raged until he had run out and lay tear drenched against his pillows, listening to Finwë rise from the bed and summons a servant to bring a plate of fruit.

Then he washed and dressed Ingwion like he was a child in need of assistance.

“Go to your son,” Ingwion whispered. Finwë kissed him and carried Ingwion again to the courtyard and watched the drip feeder for the humming birds while Ingwion recovered himself.

“Did your father ever give you a name beyond Ingwion?” Finwë asked quietly, eyes unwavering from the drip of the nectar onto the plate.

“None,” Ingwion watched Finwë, he had seen the birds come to feed before. He was uninterested in the barest flash of green or blue wings when he had Finwë sitting before him with his hair catching the light and flash blue, green, purple, silver, or become solid matte black depending on how his head tilted.

“I asked him once, he said I did not need another name but his for inheriting from him was the most important thing I could do.”

“I was vain like that once. No wonder Míriel scored our son with her poetry.”

Then it was fitting that it was Rúmil Lambengolmo who had the child now, Ingwion though but his rage was crumbling against the sorrow that had carved fresh new lines into Finwë’s face.

“What of your mother?” Finwë asked him, “she did not give you a name?”

“I do not remember my mother,” Ingwion shrugged, “or rather my memories of her are so few that they barely make sense and I might as well not remember her at all.”

“I am sorry for that,” Finwë bowed his head. Ingwion wondered what he was thinking of. Finwion left in Tirion? Who invented wonders even in youth so incredible that sometimes they did not even turn what they knew on their head but created a whole new field of knowledge?

That incredible marvellous son who had done more in his small years then Ingwion had managed in a life that recalled Cuiviénen.

“I grieved her though,” Ingwion said, “long after everyone else did. When I realised she was dead. For no one told me, and I lived with an absence I was sure would be filled one day by her return.”

She had driven herself hard to prove herself worthy of the newly anointed hope of their people, freshly returned from Aman to find the woman he’d dallied with had given him a son.

She had driven herself too far.

“Will you wash your hands of me?” Finwë sounded impervious to the answer but Ingwion thought that probably only meant it was worth a great deal to him. Why display stoicism now after all that had passed in such a short space of time.

“Probably not. Will you of me?”

“We have likely committed a great sin,” Finwë did not sound repentant, simply acknowledging what they had done.

“None have noticed; we are not cast down by Holy Retribution. Unless you wish to finish this now?” Ingwion challenged, “now that you have had your way with me. If you are bored of me or find me too cloying tell me.”

A return of light to Finwë’s eye, “there are many more ways I would have you,” he stood and pushed at the gates of the courtyard and Ingwion followed into the walled corridor garden that wrapped the palace.

“I see no boredom in your company,” he was pushed against the wall, legs spread apart, “you bring me a light in the darkness. Cling all you want to me Prince Ingwion.”

It was both rough and sweet. Ingwion sighed when he found release, sore and at the limit of what his body give now.

“I need to let you rest,” Finwë kissed his shoulder and pulled away, making Ingwion moan in regret and relief, “I cannot seem to find a quality of self-control towards you. I am giddy as though returned to being a young man myself.”

Ingwion smiled, “giddy is fine but are you happy Sire?”

“Yes I am, enough to balance the sorrow.”

Finwë redressed him and they walked on until they emerged in the palace gardens proper with its tall hill leading the eye up to the mountains and the jewel of Manwë’s abode. The whole vista was framed by sculpted bush and flowering trees raining petals down on those below.

Ingwion saw the flash of her hair amongst the manicured hedges. Indis’ pale face as she leant out of one of the windows in the leafy wall to see where Finwë strayed. Her teeth bit down on her lip yet he saw a ripple of determination go through her. There was a straightening of her shoulders, a preparation in her body.

Ah yes, he recalled, his aunt had hunted once also had she not? But she had been the kind to lie in wait; good at coming upon what she desired when it was least suspecting. She might be able to run a deer to the ground in exhaustion but why waste such precious energy when surprise worked better?

Ingwion moved quickly, broke his own wait and moved on clumsy legs and with far less skill than Indis to grab Finwë’s arm so that even when the first note of song above their head broke free to be more sweetly gold and silver than the air around them, Finwë looked to him.

“Dine with me tonight,” he offered, requested, begged, “show me more of the ways you spoke of.”

Finwë’s nod, face cast into shadows by the light, was hardly discernible with the mourning shroud of his hair falling down around his face and hiding the subtle motions of his neck. It might just have been the breeze that made it sway.

Indis’ song took on a brighter tone and Finwë’s head was turning; turning towards the glittering peal of hope. Ingwion tightened his grip enough to turn Finwë’s face back to his and laced their hands together, pressing his fingers against Finwë’s gold ring.

Finwë caught him with his other hand behind Ingwion’s head and kissed him without any modesty and the song upon the hill died. From the Mountain came a wind of cutting cold. It disturbed the ever present crows who had settled in the flowering trees, and they shrieked their discontent.

“Would you cast her down?” Finwë asked against his mouth, “would you lay her on the ground and pin her there and place a knife to her flesh while you describe to her every way that you will ensure the Rider in the Dark will tremble hearing your name when you are done with her?”

“Yes,” Ingwion trembled at the thought but it was a satisfied reaction because what he had described felt right to him.

“Will you come to Tirion with me? Befriend my son? Endure my dark moods when I dwell upon the fact I will have no more children? Bear my grief at the loss of my wife? Bed me when Míriel is likely a third partner and the bed is my marriage bed?”

“Yes!” This was madness born from one week of ever having talked to one another beyond platitudes. But to stay here now with only endless days of hunting and the court and his father’s fading prayers? No give him this for as long as he could hold it, “more than that I will mourn her with you.”

Finwë’s eyes widened. He stared. Then trembling he brushed petals from Ingwion’s hair.

“If by some chance her diamond-hard will shatters and she returns?”

“I will bring no conflict to your family Sire, I will make no demands upon what is rightfully hers and your son.”

“Did you meet Rúmil Lambengolmo when you were in Tirion,” Finwë slipped from his grasp, his net, and turned towards the bower of roses Aunt Erdawë had planted with her family to celebrate her first grandchild.

“I did,” the scent was cloying as they passed through into the blossomy wonderland. Finwë ignored the richness around him in favour of walking to the centre of the bower where a small alter was kept pristine and where Ingwë could sometimes be found lingering, “I did not have time to talk to him though.”

“You shall have to, for a Vanyarin prince of the type that has inspired more than one of his poems is not someone he will let pass by.”

Ingwion stared at Finwë’s back.

“You lie. With his grudge I expect nothing about the Vanyar except for rude limericks.”

“I do not. He is not so petty. Even in that poem you admire he found some inspiration, perhaps even from talk of you; 'the hunter's heart, the hunter's mouth, the trees and the trees and the space between the trees, swimming in gold.”

“That is merely the final verse,” Ingwion hurried to catch up, “he means the dawning of Laurelin.”

Finwë cast a smile over his shoulder, “that is a noble and fitting epessë indeed for you Prince Ingwion.”

Chapter End Notes

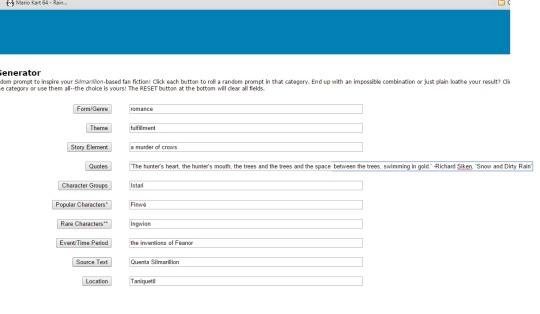

"the hunter's heart, the hunter's mouth, the trees and the trees and the space between the trees, swimming in gold." is from 'Snow and Dirty Rain' by Richard Silken. It was the quote given to me by the prompt generator. The rest of the poem provided some good inspiration too.

I usually envision the Two Trees as twined together and upright. The imagery for vines that trail all over Aman was inspired by MotherofBees art!

Original prompt: