The Silmarillion: Who Speaks? by Dawn Felagund

Fanwork Notes

Back in 2019, I wrote a blog post called The Inequality Prototype. As part of it, I counted a bunch of stuff related to the Valar and looked at how those metrics differed based on gender. At the time, I thought it would be interesting to extend this work over the entire Silmarillion, namely looking at who speaks in the text and who doesn't.

For Tolkien Meta Week, I began this work and am collecting my analyses related to it here. It is very much still a work in progress and will likely take me years to complete.

As with all of my data, I am making the dataset and analyses available under a Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial Share-Alike license. What this means is that you can use my data as long as you're not profiting off of it and you also make your work available for others to use under similar terms. You can make a copy of it and build on it and post/publish your own work using it. You don't have to ask (the CC license is permission!) but credit me if you do as Dawn Felagund (in fanworks) or Dawn Walls-Thumma (in scholarship) and, if possible, link back to my website at dawnfelagund.com. I also appreciate if you let me know what you do with the data so that I can read it!

Methodology

I have used an unauthorized digital copy of The Silmarillion to perform word counts, using the Word Count tool in Google Docs. I own a Kindle copy, but Kindle imposes limits on how much text you can copy. I swear, Tolkien Estate, I am not illegally selling Silmarillions; I am just a data nerd. Given this, though, there might be minor discrepancies in word count.

When counting words:

- Only dialogue (between quotes) is counted. Dialogue tags or interrupting action are removed before calculating a word count.

- New paragraphs are counted as new dialogue (unless uninterrupted dialogue is divided into multiple paragraphs without interceding action; Fëanor has a couple of speeches like this, for example).

- Thoughts in the form of dialogue are not included.

- Remembered dialogue that repeats earlier dialogue is not included (e.g., Ulmo's warning to Turgon).

Project Progress

Phase 1

Phase 1 will document all dialogue in The Silmarillion. This is the current phase of the project.

- Collect all instances of dialogue from The Silmarillion using a search of the text for single quotation marks: Complete

- Check the first collection of dialogue by reading the text for dialogue: In Progress

- Classify dialogue by character, group, subgroup, and gender: Complete

- Classify dialogue by canon source and type of dialogue: Not Started

- Compile statistics on dialogue in The Silmarillion: In Progress

Phase 2

Phase 2 will document instances where a character is indicated as having spoken but is not given dialogue. Phase 2 has not begun.

Phase 3

Phase 3 will document instances where a character is indicated as not speaking or as staying silent. Phase 3 has not begun.

Fanwork Information

|

Summary: On ongoing project to analyze who speaks in The Silmarillion and who is silent. Major Characters: Túrin, Fëanor, Melian, Elu Thingol, Mandos Major Relationships: Genre: Nonfiction/Meta Challenges: Rating: General Warnings: In-Universe Intolerance |

|

| Chapters: 5 | Word Count: 3, 266 |

| Posted on 26 December 2024 | Updated on 4 January 2025 |

|

This fanwork is a work in progress. | |

Dialogue by Chapter

Read Dialogue by Chapter

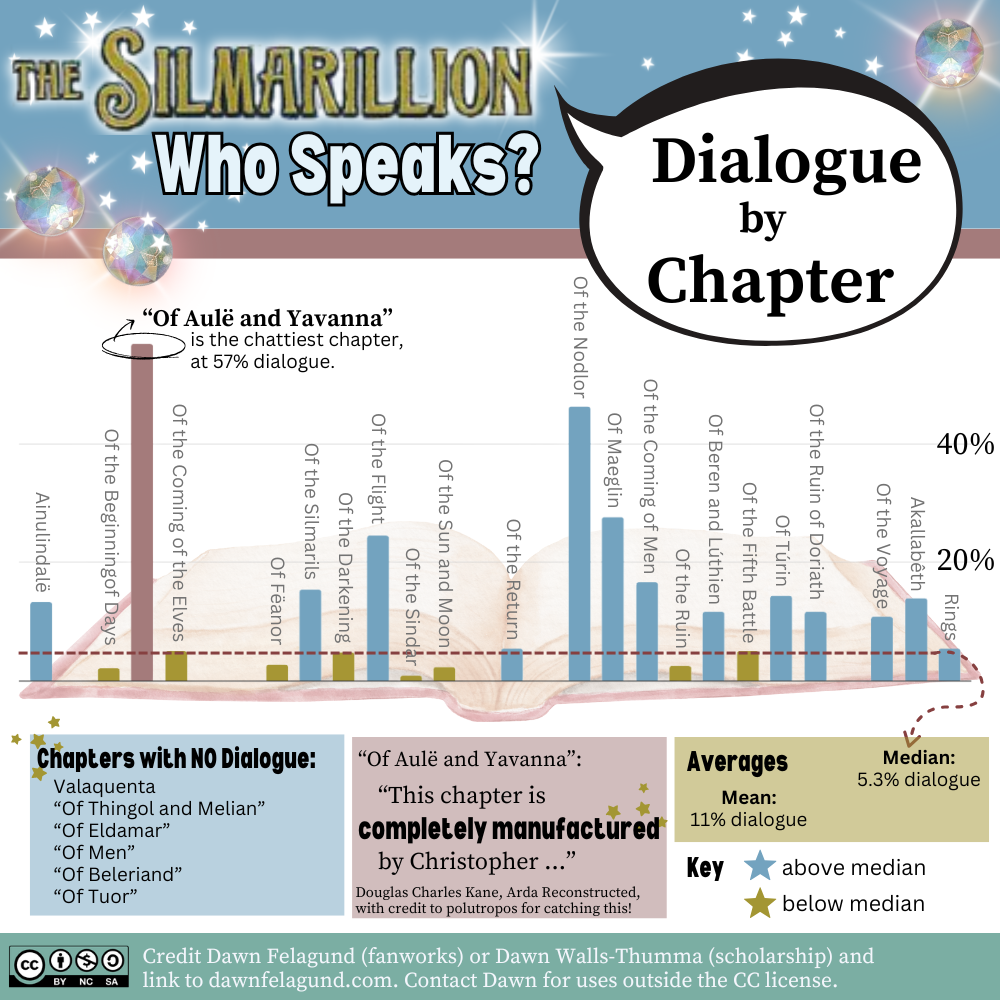

Dialogue does not occur evenly across The Silmarillion. While a little over 5% of the words in The Silmarillion as a whole are used in dialogue, this is very unevenly distributed across the chapters, with some chapters about half dialogue and six chapters containing no dialogue at all.

There is a lot more work to be done to tease out trends and patterns that might have some meaning, but just glancing at the graph above, some of those patterns do begin to emerge. First, dialogue increases as The Silmarillion progresses. In the second half of the book (calculated by chapter, not page or word count), only two chapters have no dialogue and only four chapters (inclusive of those two without dialogue) fall below the median of 5.3% dialogue. Put another way:

- In the first half of chapters, 71% of chapters are below the median.

- In the second half of chapters, 29% of chapters are below the median.

Why is this? My tentative theory is that we see the book moving from the realm of the mythic—from events that are passed down through the oral tradition and ancient written traditions—and into the historical, where the narrator has a greater array of sources, including eyewitness testimony, and begins to write with greater immediacy rather than the arm's-length style of myth and ancient history.

What I am curious about: As I dig deeper into these data, will I see this theory bear out in which episodes or characters/groups are granted actual dialogue? In other words, will characters and peoples lost to the mists of time speak less, as I would expect? Or will the type of dialogue (e.g., a formal speech that may have been preserved vs. an extempore conversation that would not) vary based on narrative distance? I have documented in the past that the narrator of The Silmarillion uses the "it is said/told/sung" construction more with characters who are less accessible, so there is evidence that Tolkien manipulated writing style based on what his narrators' access to various sources. Does he use dialogue similarly to communicate that "mythic distance"?

There are also chapters that are more expository in purpose (Valaquenta, "Of Beleriand and Its Realms") that do not contain dialogue. Without digging deeper into the chapters themselves, most of those without dialogue that aren't similarly expository are chapters where the material would be less accessible to Pengolodh as a narrator. Whether this bears added scrutiny remains to be seen!

Finally, in discussing these data on the SWG's Discord, polutropos noticed something interesting, which is that the chapter with the most dialogue—"Of Aulë and Yavanna," where almost 57% of the words of the chapter are given over to dialogue—was not in fact written by Tolkien. As document by Douglas Charles Kane in his book Arda Reconstructed, "This chapter is completely manufactured by Christopher, though using his father's own writings" (page 54). Where Kane usually includes a chart pointing to the source for each bit of The Silmarillion, his chapter on "Of Aulë and Yavanna" contains no such chart because, while he is able to document where ideas came from, Christopher actually wrote the chapter.

Interestingly, "Of the Noldor in Beleriand" is the chapter with the second most dialogue and, according to Kane, "The changes made in this chapter are among the smallest anywhere in the published text" (page 154). So Tolkien does sometimes write dialogue-heavy chapters—though without data to back me up (yet! it's coming!), most of that dialogue appears to come in the form of lengthier speeches, not necessarily the debate/conversation format of Of Aulë and Yavanna."

The biggest impact of the dialogue-heavy "Of Aulë and Yavanna," I suspect, will emerge as I dig more into the data on gender and who speak in The Silmarillion. Yavanna is one of the women who speaks the most in The Silmarillion, but almost all of her dialogue occurs in this chapter. If this chapter is constructed by Christopher, how does that impact the amount of speech women are permitted by Tolkien? Polutropos' observation spurred me to plan to document the source of the various dialogue sections: Are they original to Tolkien's writings or added? Kane, interestingly, is critical of Christopher Tolkien in Arda Reconstructed for what he perceives as Christopher removing women characters from the text. In this instance, we see a significant example of the opposite: a woman's role is not only expanded, but she is given an opportunity to speak.

Dialogue by Character Group

Read Dialogue by Character Group

The whole reason I decided years ago that I wanted to count instances and words of dialogue is because who gets to speak matters. Who gets to tell their own story in their own words?

(And, for the record, in this data set, "dialogue" is measured in instances of dialogue, not in word count.)

Of course, in The Silmarillion, it is more complicated than that because The Silmarillion is a pseudohistorical text, so we have to constantly question whether what the narrator is telling us happened (or is said) was in fact what happened (or what was said). The prevalence of group dialogue in The Silmarillion—when specific, quoted speech is attributed to a group of characters rather than an individual—attests to the inexact science that is dialogue in the text. There are twenty-six instances of group dialogue across the book.

So it would perhaps be more accurate to say that dialogue matters because it indicates who the narrator wants to allow to tell their story in their own words with the authority that comes from being important enough to quote.

Which groups of characters get to speak aren't surprising, but this does still tell us something important about the perspective we are given in The Silmarillion. Elves speak the most, but The Silmarillion is an Elven history, so we'd expect that. Within the category of "Elves," though, speech is entirely dominated by the Noldor and Sindar. One Teler (Olwë) gets a single instance of dialogue, and the Green-elves get to speak once as a group.

Why are these characters' perspectives absent? Does this simply reflect a limitation of the narrator, or is the narrator foregrounding the experiences and perspectives of Noldor and Sindar as more valuable—worth quoting?

Mortal Humans and Ainur speak almost the same amount. I find this interesting because, as I noted in the graphic, the Ainur made a big deal about flouncing from Middle-earth after the Noldorin rebellion. Yet they sure have a lot to say about things. In contrast, after they arrive in Beleriand, Mortal Humans are always at the hub of the action. Someone is always getting shot through the eye or something. Yet their stories, in their own words, are told only a bit more than the intoning, cursing, and speechifying that the Ainur get up to.

When Mortal Humans do speak, they are always "Men of the West": Edain, Númenóreans, or Dúnedain. We do not hear once from other groups of Mortal Humans, such as Easterlings, even speaking as a group. This certainly calls into question the absence of those perspectives from the story. Think about it: the Silmarillion narrator finds God a more accessible, quotable source than an Easterling soldier.

All of this corroborates other data and observations about Mortal Humans that I've made over the years (for example, the death data). Our Silmarillion narrator often seems to include Mortals almost grudgingly because, yes, they did important stuff in the story but tends to see them as ephemeral or expendable and really only likes to talk about them when they are doing cool stuff with Elves.

These data do add an interesting (to me anyway) perspective as well on the question of the Silmarillion historical tradition. In a nutshell, in the late 1950s, Tolkien considered that the historical tradition must be Númenórean, not Elven. Even though there was no strong evidence that he made significant revisions with this change in mind, it was enough for Christopher Tolkien to scrap mentioning a narrator in The Silmarillion at all, and several scholars have followed suit in asserting The Silmarillion is a "Mannish" history.

I have been a fiction writer much longer than a Tolkien scholar, and one does not simply walk into changing point of view. I've made the case for years now that Tolkien realized the depth of revisions that would be required and either changed his mind or just never got started on them. Regardless, the text we have is Elvish. These data support that: the predominance of Elven and Ainurian perspectives attest to a narrator whose main sources are Elves and Ainur and who subtly but nonetheless devalues the perspectives of Mortal Humans, even though they are the grist in the mill of the war against Morgoth.

Finally, there are Dwarves. The only named Dwarf who speaks is Mîm, in the "Of Túrin Turambar" chapter, which is an outlier of a chapter in its use of dialogue (it also has a different narrator) and which will probably gets its own analysis someday. Otherwise, Dwarves speak in groups. As with Mortal Humans, these data align with other data and observations I've made over the years of the status of Dwarves to the Silmarillion narrator. In this case, they are valued but often inaccessible—the opposite of Mortal Humans.

Methodology Notes

As already stated, all data are instances of dialogue, not word or sentence count.

Classifying Elves into subgroups is remarkably challenging. Here's how I did it for this project:

- "Noldor" includes characters who have Telerin or Sindarin ancestry in addition to Noldorin.

- "Teleri" includes only characters with only Telerin ancestry who live in Aman.

- "Sindar" includes only characters with only Sindarin ancestry who live in Middle-earth; mixed Noldorin/Sindarin is not included; Lúthien is included.

Finally, the "Other" group includes animals, dragons, Orcs, objects, and speakers whose identity is not stated even enough to determine what group they belong to.

Dialogue by Gender

Read Dialogue by Gender

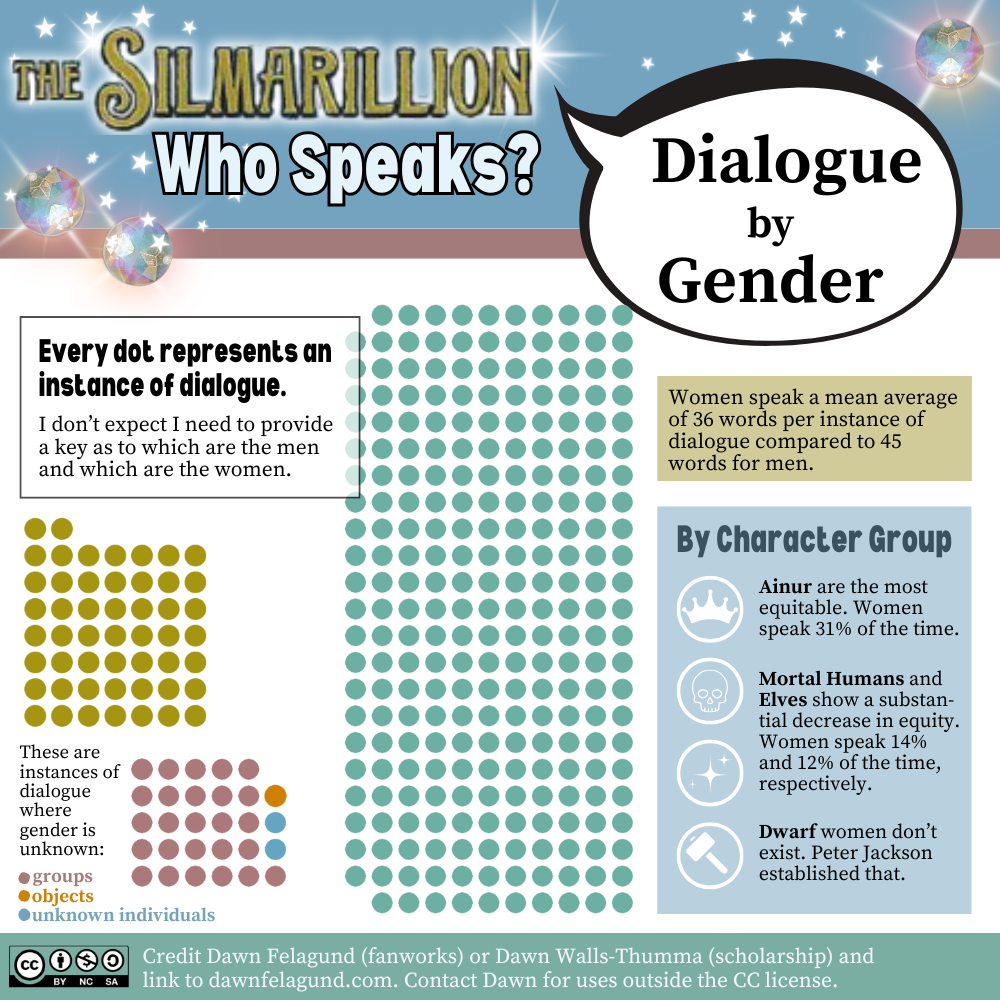

I expect the outcome of these data will surprise no one. Women speak less, and women speak less. This isn't a typo: It means that they have fewer instances of dialogue in The Silmarillion by a substantial margin, and when they do speak, they speak nine fewer words than men, on average.

Instances of women speaking is much nearer to speakers of unknown gender than to men speaking. (And before we get excited and think that the "unknown gender" speakers are rejecting the gender binary, this category represents mostly dialogue attributed to a group, plus two unnamed individuals who are given dialogue and one sword.)

This matters because dialogue signifies several important things in The Silmarillion. First, in a pseudohistorical text like The Silmarillion, direct quotes mean that someone said something important enough to preserve in the historical record. Men, based on the data, are saying far more important things than women, at least in the various narrators' estimation. Next, dialogue is often a proxy to action: Characters debate, give directives, and make speeches. Dialogue also humanizes, and even though Tolkien rejects many modern literary techniques in The Silmarillion, he does use dialogue as a characterization technique. As I will show in future analyses, some characters are distinguishable based on how they speak.

Of course, the reduced dialogue of women in The Silmarllion is a direct effect of there being significantly fewer women than men: Women constitute only 19% of the named characters in The Silmarillion. Even given this, however, women speak less than we would expect.

When we look at character groups, there are notable differences, namely that women of the Ainur speak more than Mortal Human and Elven women do. (Only four Elven women and five Mortal Human women speak in The Silmarillion! Excuse me while I scream!) This was the thesis of the long-ago Inequality Prototype that spurred this data collection endeavor: The Valar, being prototypical, show an equal penchant for entering into the world based on gender: It is a 50/50 split. So we can't say that women have less desire to influence the world than men in the legendarium. When we see less action and fewer instances of dialogue among women, then, we have to ask why.

Complicating the data for the Ainur (overall, not just this set) is the fact that a big chunk of their dialogue occurs in the "Of Aulë and Yavanna" chapter that Christopher Tolkien wrote. I don't want to treat these data differently until I have the opportunity to collect more data on where dialogue outside this chapter comes from; for all I know, Christopher wrote most of it! (Actually, I know he didn't, but this chapter does illustrate how his additions can skew data for a particular group, in this case the Ainur.)

Another future area of inquiry will be the type or purpose of the dialogue and whether/how this varies based on gender. Characters speak for many reasons. Do women speak for different purposes than men?

If these data illustrate anything to me, it is the importance of fanworks in amplifying the voices of women characters who we know existed and know said and did things that mattered. We are being given a historical record much like our own Modern-earth historical record: biased toward the contributions of some over others. Only we can fix that.

Who Talks More Than God?

Read Who Talks More Than God?

The last couple of days have been heavier topics, with data on who speaks by gender and character group, so today seemed a good day for a post that is only semi-serious!

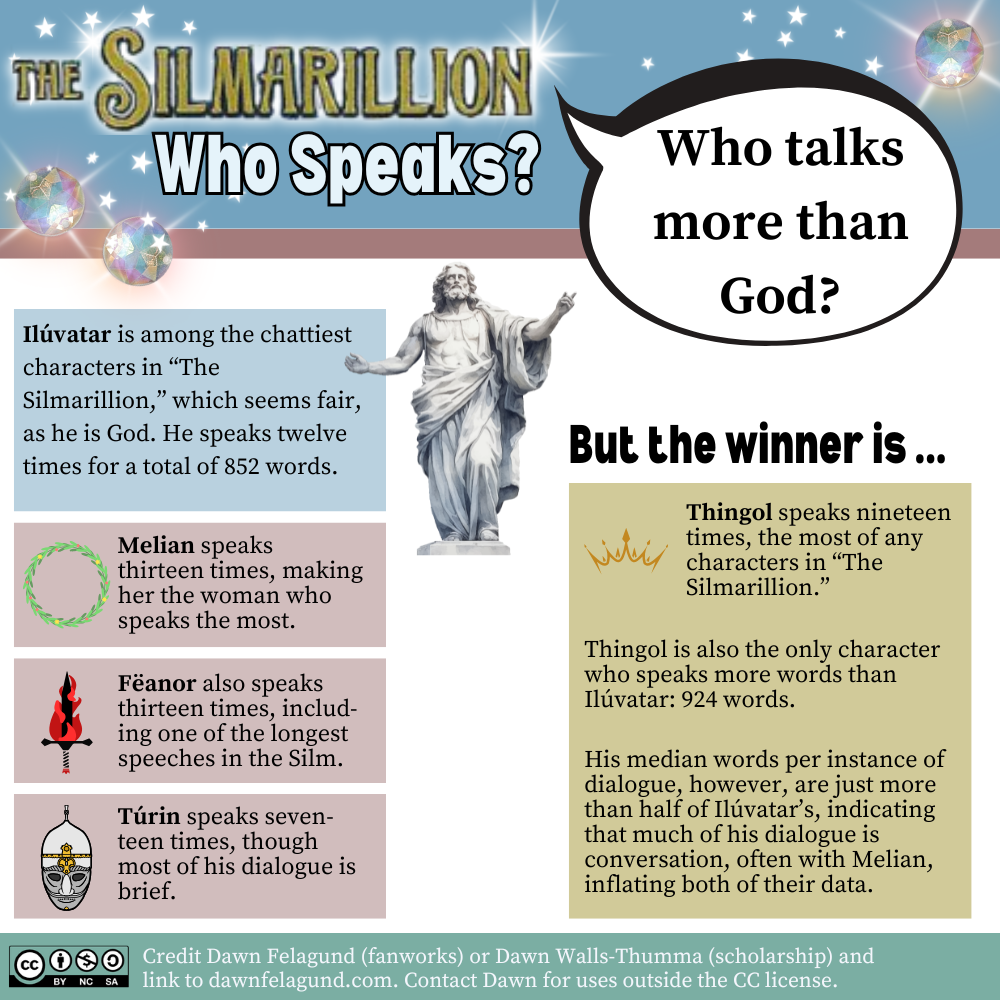

Because it doesn't actually mean much to talk more than Ilúvatar in The Silmarillion. Ilúvatar has a lot of lines and is prone to speech-making so has a high word count as well, but it's not like the four characters who speak more than him are trying to one-up God or anything. But we're Silmarillion fans and anything related to our characters feels political, so it's fun to consider which of them talk more than God.

In fact, the four characters who do are interesting in part because their dialogue is so different. Melian's dialogue is mostly in conversation, with Thingol or Galadriel. Fëanor has a variety of different dialogue but also makes some lengthy speeches; his speech to the Noldor prior to their exile is the third longest in the book (excluding two instances of "group speeches"). Túrin is the exact opposite: He speaks a lot, but his instances of dialogue are unusually short. The median length of an instance of dialogue across the book is thirty-one words, but the median for Túrin's dialogue is twenty-one words.

Thingol, of course, comes out on top as the character who speaks the most instances of dialogue AND the most words, topping Ilúvatar in both of these categories.

Returning to Melian and continuing yesterday's discussion of gender and speech, the woman who speaks the most after Melian is Yavanna, with ten instances of dialogue (most of them in the Christopher Tolkien-authored "Of Aulë and Yavanna). This means that Melian and Yavanna speak more than half of the dialogue uttered by women in The Silmarillion.

Of course, I'm always interested in pseudohistorical readings of The Silmarillion, particularly thinking about who is telling the story at what points and how the story Tolkien gives us is shaped by narrative point of view.

In this case, Thingol as the top talker makes sense given that the Beleriandic materials were collected by Pengolodh, who counted as a major source the refugees from Doriath who migrated, as did he, to Sirion's mouth. Dírhaval, who is credited with Túrin's story, would have likewise heard much of Thingol (and Melian) from his sources. It makes sense that Thingol, Túrin, and Melian are written with more immediacy than other characters are, who likely felt less accessible to the narrators.

What about Fëanor? The Aman materials were authored by Rúmil and passed to Pengolodh. I've always felt like Rúmil's sections portray Fëanor with more humanity than Pengolodh's sections do, though I've not yet drilled down into the data on this. The dialogue data seems to support that, at least, Rúmil perceived Fëanor as a character important enough that his words were worth preserving. That may seem like a "doh" statement, but consider how many important moments throughout The Silmarillion occur without us hearing dialogue from anyone at all. Multiple of Fëanor's speeches, on the other hand, were preserved.

Námo Mandos

Read Námo Mandos

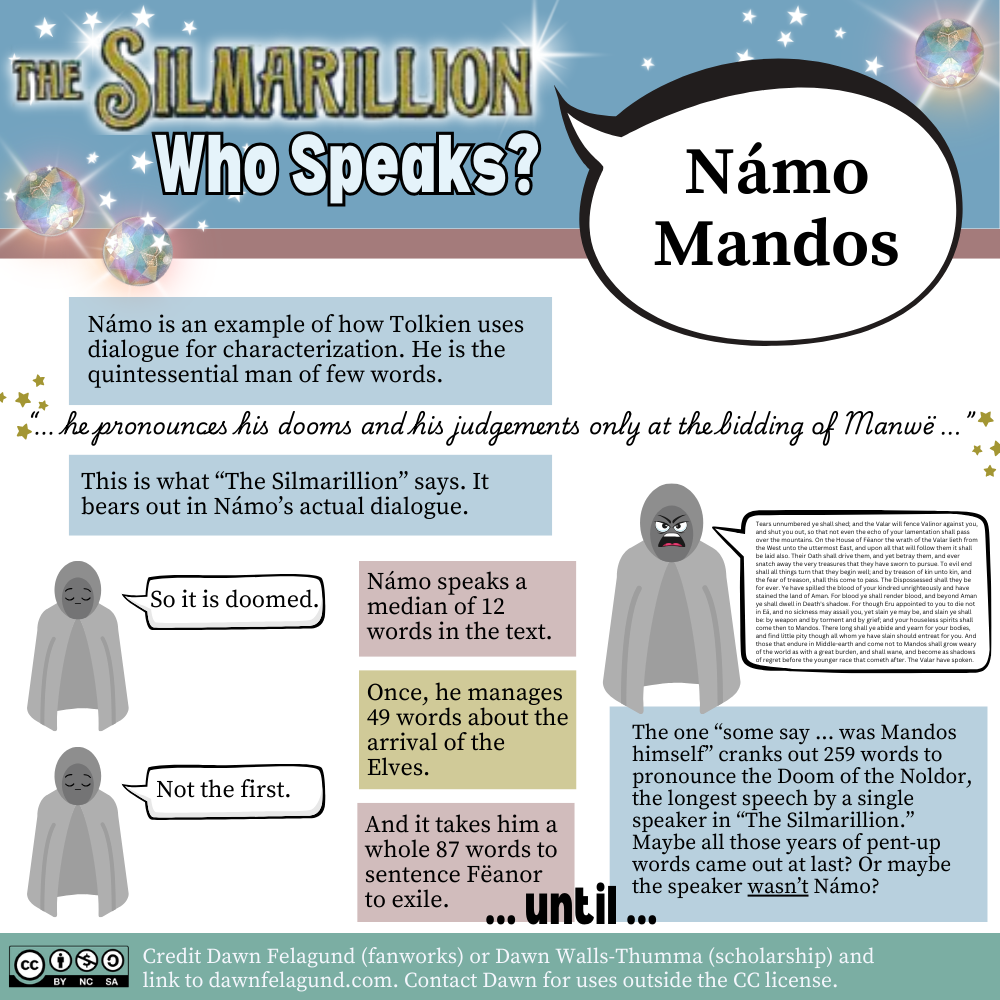

We don't often think of The Silmarillion as a text that uses modern literary strategies, like indirect characterization through dialogue. However, Tolkien absolutely characterizes using dialogue. Some characters have distinctive patterns in their dialogue, for instance. Námo Mandos is one such character.

Námo is a man of few words. The Silmarillion states that he speaks his judgments at the bidding of Manwë ... not only that, but he speaks very few words, even when pressed to do so.

Námo speaks eight times in the text with a median of twelve words per instance of dialogue. Across the entire book and all characters, the median number of words per instance of dialogue is thirty-one words, so Námo is well below average.

Until he isn't. As the Noldor leave Aman, "they beheld suddenly a dark figure standing high upon a rock that looked down upon the shore. Some say that it was Mandos himself, and no lesser herald of Manwë" ("Of the Flight of the Noldor"). This guys churns out 259 words, more than three times his next longest speech and twenty-one times longer than Námo's median dialogue length. It is the longest dialogue by a single speaker in The Silmarillion.

What is happening here? There are a few possibilities:

- Tolkien uses this single long speech in contrast to Námo's seven other much shorter instances of dialogue to emphasize the importance of this speech. Along those same lines,

- the Doom of the Noldor, along with the Oath of Fëanor, form the "explanation of history" used by the narrator of The Silmarillion. Just about everything bad that happens, the narrator finds a way to tie back to these. Again, the length of the speech—especially coming from a character who is succinct verging on terse—emphasizes the centrality of the Doom of the Noldor. We understand that Námo only speaks when it's important, and he says a lot here, so it must be really important.

- Is the speaker even Námo? The language "some say" creates doubt; it relegates the identity of the speaker to the realm of rumor. Again, thinking about the narrator, the uncertainty allows for the possibility that the narrator elevated a theory that confirms his understanding of history without having firm evidence.

- Or maybe the anomaly is a characterization strategy. Tolkien writes a character who speaks very little. In this scene, he speaks a lot. And I do mean A LOT. What does this say about Námo's frame of mind in this scene? He suddenly unleashes a torrent of dialogue where he spoke minimally or not at all before, perhaps an indication of distress, sorrow, frustration? It is further interesting, considering that his second longest instance of dialogue was also Fëanor-related, to consider what this shows of his feelings toward Fëanor. Is this the Silmarillion version of the modern comedy trope where the strong, silent type suddenly lets loose the outpouring he's been holding in all this time?

Regardless of the theory you prefer, Tolkien uses dialogue here to raise questions about characters and about history.

what an intriguing project

To this person for whom numbers generally have very little "colour" this is surprisingly interesting!

Because of the double effect of Tolkien not finalising anything and Christopher inserting his bias/preferences, I'm often wondering how a JRRT-published work might have finally appeared.. (Although even if he lived as long as Elros I'm sure he would have still been changing his mind throughout and would still not have finished!)

That is truly a wonderful…

That is truly a wonderful compliment if I managed to make dry old dusty numbers come even a little bit alive for you!

I wonder about that a lot too and tend to end up with JRRT never being able to finish a "Silmarillion." His purpose changed so much between the Lost Tales and some of his late writings where he was completely reconsidering the cosmogony and historical transmission. I also wonder if the constant rewrites weren't part of the purpose. Intended or not, he did create a historical tradition right in the drafts of his work ...

Thank you for reading and commenting! <3

It's your extrapolations…

It's your extrapolations that make this so interesting. I mean, the way I read, I originally read the whole Silm as an omniscient view, and never even noticed that Turin's chapter might be a different narrator. Just learning about JRRT's narrators and their likely biases changed the Silm dramatically for me. So extending that view by delving into this dialogue aspect is opening my eyes even further.

I agree that, with the published Silm being cobbled together from various (often incomplete) writings spanning decades of mind-changes, we end up with quite a jumble. And yet I'm also really glad we do, because I love the magic and whimsy of his early ideas as much as his later writing, and I think the Legendarium would be far less rich and engaging without either.

I'm also wondering how much of the Ainur's dialogue is Aulë and Yavanna having their domestic?

To be fair, I didn't realize…

To be fair, I didn't realize that Turin's chapter was a different narrator until REALLY recently given how long I've been working on stuff with the narrators. XD And that's my least favorite chapter so I'm still not 100% sure how it is constructed from its extremely complex textual history. Right now, my slightly informed stance is that Dirhaval wrote the verse version and our good ol' pal Pengolodh put it into prose in the book we call The Silmarillion. But this is probably 75% headcanon at this point.

Because you, like I, enjoy maps, you might enjoy this atrocity that I made for my "Death, Grief, and the Other" presentation at Oxonmoot in August:

(Why didn't I color in the ocean? The mind boggles!)

(And Sirion is spelled wrong!!!!)

I absolutely LOVE that the Silm is a posthumously published textual jumble. (That is the perfect word for it!) It feels like real history, where you have to wade through sources and debate their various merits. This is why, while I have to stop short of saying "Tolkien intended," I do wonder if someone who worked with medieval texts in all their various and contradictory forms wasn't maybe a little bit intentional about creating a similar tradition. I don't think he wanted to leave it unpublished, but there would have been this whole iceberg of texts under the surface ... and of course the doubt that a fallible narrator creates.

Yes, as I'm working with the data, I'm realizing that this is coming up again and again as a complicating factor. I probably need to dig into the provenance of the various instances of dialogue that I've collected sooner rather than later, then see how the data changes (or doesn't) once Christopher's additions are filtered out.

I am amused by the "who…

I am amused by the "who talks more than God?" question - and even more so by the answer(s)!

This is even more fascinating.... [Ch. 1]

....than the discussions in Discord. The Aulë and Yavanna chapter containing the most dialogue (and by a female) but written by Christopher Tolkien rather than his father is an astonishing fact.

Definitely, definitely written by elves [Ch. 2]

The bias of the Silmarillion always felt Elvish to me, so was happy to see that your research bears this out.

Female invisibility [Ch. 3]

We all know this is an issue, and the statistics are stark. And, as you say, thank goodness for fanfiction.

Being a Fëanorian fan.... [Ch. 4]

....I am usually wanting more about the lives and motivations of his sons (and any adjacent/non-adjacent females, or other genders*), rather than the father who disappears from the scene leaving the Oath in his wake. As for Thingol talking more than everyone else, while he was making his bad and/or potentially bad decisions, fanfiction to the rescue again....

*actions/pronouncements/events of January 2025 related

Probably my favourite piece of.... [Ch. 5]

....statistics* from your report (which has overall been a great read). I love the possible permutations of Námo's journey to expressing himself at length.

*Statistics was my one and only grade below B at University.... Calculus made sense; Engineering, Literature, Architecture, History all made sense; Statistics just wouldn't go in.