Mereth Aderthad Interview: Interview with Paul D. Deane by Himring

Before the Norman Invasion brought rhymed poetry with it, English poetry was alliterative, and this early poetic form held deep appeal for Tolkien. Himring spoke to Paul D. Deane about his upcoming Mereth Aderthad paper "Love, Grief, and Alliterative Verse in Tolkien’s Legendarium" and his work with alliterative verse, Tolkien, and alliterative verse about Tolkien.

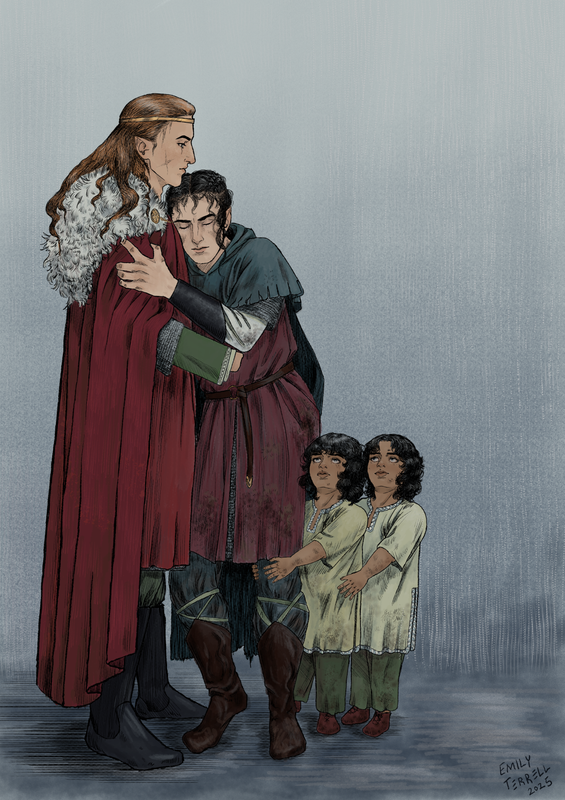

And Love Grew by polutropos

As Little Might Be Thought

Elrond and Elros find themselves at risk of being left without anyone to protect them and face their most difficult trial yet. The journey ends.

“Do you think she was really his sister?”

“He said she was his sister.” Elros was sullen and did not look up from the stream. He’d been stabbing repeatedly at a stone lodged in the bank for several minutes, knocking away chunks of mud.

“You should stop that,” said Elrond. “You’ll make the whole bank collapse.”

Seated on a rock behind them, Bornval huffed with amusement. “Takes far more than a few pokes by a little boy to make a bank collapse, even if it is just a stream.”

Elros ignored him and kept on. They did not like Bornval. He had a voice that scratched and long spidery limbs. He braided his hair back so tight it pulled his face taut.

Elrond looked back through the trees, where he could just make out Maglor stooped over the mound heaped atop his sister’s body. If she was his sister. Elrond felt badly for disliking her, now that she was dead. Maglor sat upright on his heels and stared ahead. Then he began to sing: low, sombre notes Elrond could feel more than hear.

He did not understand why Maglor sent them away. He and Elros had seen people die before; they had seen burials before. Many, many times. Perhaps he did not want them to see him weeping? But they had seen adults weeping many times, also. Sometimes, when Papa was away, Mama shed tears every day. She would shed happy tears when Papa returned.

Abruptly, Elros threw his stick at the ground and shouted. “I wish we were dead, too!”

“Elros! Don’t say such things!” Before he was aware, Elrond’s arm had leapt from his side and he’d smacked his brother in the chest. “Sorry,” he said at once, horrified.

Elros’ burst of emotion seemed to flee as quickly as it had come. “It didn’t hurt.” He started picking at his nails.

Bornval muttered to himself. Elrond could not believe he had heard him right. “What?”

“I said, you would be better off dead.”

So Elrond had heard him right.

“You cannot say that!” said Elros. He was right. It was not the sort of thing adults said to children. It was not the sort of thing anyone said to another person, unless he was especially angry.

“I have seen too much not to speak the truth, child,” said Bornval. “It is a wonder you have survived as much and as long as you have. Your line has a way of surviving, though. The Valar favour you.” He scoffed. “Not enough to save you now, it seems.”

“Stop it, stop it, stop it!” Elros cried. “We are going to live and we are going to become warriors and we are going to avenge our mother!”

Elrond wanted to say something but he had gone still and cold.

“Quiet yourself,” said Bornval. “Avenge your mother, will you? And who is to blame for what became of your mother? Your mother chose a stolen jewel over you. Then she slew herself. Your revenge is already exacted.”

“No!” Elros screamed. “No, no, no! You are wrong. That is not how it happened.”

“Elero!” Elrond cried, but he was too late to stop him. Elros abandoned the large stone stuck in the bank and grabbed another, too big for him. He hurled it at Bornval all the same, and it landed no more than two paces from where Elros stood. Frustrated, he stomped and balled his fists; he made a mad dash at Bornval.

The elf rose from his seat. To Elrond’s horror, he pulled a knife from a sheath at his hip and blocked himself with it. A knife! He could not seriously believe Elros posed a threat to him, could he?

“Stop, fool,” he said, but it was unnecessary because Elros had staggered to a halt the moment he saw the weapon.

“Help!” Elrond cried. “Help, help, help!”

Then, he heard a great yell and stomping. He was too afraid to turn his back on Bornval and Elros. His mind flooded, thoughts whirling and whirling: it was Maglor running to save them; it was a monster of the forest; a deer; it was nothing, a branch falling; it could not be Maglor, for Maglor was still singing; no, Maglor was not singing, it was only the memory of his song playing in Elrond’s mind—

The great body of a man launched past him, straight for Bornval. He ran with a limp. He held aloft a great club.

“Embor!” came Elros’ little voice, barely audible beneath the man’s shouting in a language Elrond did not know. Embor was alive? Yes, yes, that was him! Speaking the tongue of his people. He was going to save them! He would take them back, as he had promised. No, that wasn’t right: they were not going back, that was what they had decided. Maglor was taking them to his home, and they were nearly there.

While these thoughts leapt about like sparks from a bonfire grown too big, suddenly Bornval was on the ground. Embor lifted his club, bringing it down on Bornval’s head. No! Elrond heard someone shout, so close and loud that it could only have been himself. Why had he said it? Bornval was cruel, he had pulled his knife on Elros, didn’t he want him to die?

Maglor came charging through the trees. His mouth was wide open; he must have been shouting, but panic plugged Elrond’s ears. Maglor seized Embor’s arm, the one holding the club, and with a twist of his whole body he threw Embor to his back.

Please, no! Elrond did not think he would be able to forgive Maglor for killing Embor. But Maglor stepped back, hands held at shoulder height with his palms exposed. Embor sat up. It was then Elrond noticed the pale tracks down Embor’s face and neck: ridges of scarring. Most of his left ear was missing. And his left arm, exposed by his torn shirtsleeves, was hollowed out near the elbow, like a chunk of flesh had been torn away, leaving behind a smooth valley of scarred skin.

At some point during the fight, Elros had run to Elrond’s side. Their hands were twined between them.

Embor panted. He did not even look at them. “You are unarmed,” he said to Maglor.

“I do not want to fight you.”

Embor laughed. Something was not right: though he was big and strong, Embor had always seemed gentle, and safe. He did not seem so now: not with his ugly scars, his matted beard, and the bloodied club in his hand. Why was Maglor not armed?

“Come, son of Fëanor!” Embor heaved his great bulk up to standing. “I have hunted you for weeks, I will not have you deny me my revenge now. Fight!”

“Son of Agida,” said Maglor, and Embor blinked. How did Maglor know the name of Embor’s father? “Tell me what I have done to earn your hatred and I will make it right. I will not fight you.”

Embor swung his club. It cut through the air, narrowly missing Maglor’s head. Elrond and Elros both flinched; Maglor did not.

“Put the weapon down,” he said, firm the way Uncle Círdan was firm when he and Elros were younger and would not share their toys with other children.

Embor did not listen. He swung again, this time hitting Maglor in the chest hard enough that the thud of its impact could be heard. Maglor gasped sharply. “Stop,” he said, his voice high and unnatural. “You do not want to do this.”

“Your soldier meant to kill them!”

“What?” Maglor’s eyes darted their way, a swift look, but long enough that he did not avoid the next swing of Embor’s club.

This time Maglor staggered, feet tangling together, and fell to his back. He coughed, dragged the breath in with ragged squeals that grew fainter and fainter until no noise came at all. He was trying to speak, but no sounds followed the movement of his lips. His eyes were seeping tears.

He snarled, a terrifying picture, and lunged. He grabbed Embor by the throat, still wheezing and coughing and sputtering spit and tears as he threw him onto his back. Embor kicked and flung his arms, but Maglor was immovable, pressing down on him. Elrond had heard that Elves could summon strength far greater than their physical form suggested, but he had never seen it. Embor could do nothing but kick and squirm and beat the ground with his fists. Maglor pushed and pushed, hacking and wheezing, clearly in pain himself, and he kept opening his mouth to speak, only to cough again.

It was horrible. It was the most horrible thing Elrond had ever seen, the way Embor’s face froze in pain and alarm. He was dead. Maglor had killed him.

Maglor knelt back on his heels, coughed, then tipped forwards onto his hands to support himself. His coughs grew shorter, less laboured. He gasped, then clutched his chest with an agonised shout. A dozen emotions Elrond could not name, some he had never even seen before, rolled over Maglor’s face.

Finally, still holding his chest, he looked at him and Elros. “Is it true? Was Bornval going to kill you?”

Elros shook his head. Elrond was not so sure his brother was right, but it had been him Bornval had held the knife to.

Maglor gave a long, thin wail and rolled his eyes towards the sky. “Ai Ilúvatar, what have I done?” The effort of lifting his neck seemed to induce another fit of coughing.

Elrond looked at the two dead bodies on the ground, and Maglor kneeling and coughing at Embor’s feet. He began to shake. What would they do if Maglor died? They would be all alone in the forest full of darkness and danger. No one would ever know what had happened to them.

His brother was so much braver than him. Elros wasn’t shaking; his arms around Elrond’s ribs were all that was keeping him upright. Pushing against the tight cage of his ribs, Elrond found the breath to ask: “Are you going to die?”

“No,” said Maglor. He wheezed. “No. I am hurt, but I will be well. Come, come. Sit near me while I lie here a while.”

What could they do but go to him? Elros slid his arms off Elrond’s body and took his hand. Elrond’s feet drifted over the ground as in a dream; he could not feel them. Elros tugged at his hand, beckoning him to sit. They sank down in a heap beside Maglor.

They marched onwards, cloaked in mournful silence. Maglor’s chest screamed in pain. The trees were thinning. The forest taunted him: laying out the path of escape even as he raced against the faltering of his lung. The pressure built against his heart. He had seen enough of war to know that the longer he went without draining the wound within him, the more likely his lung would collapse entirely; the more likely he would die.

Dornil’s imagined voice admonished him: Have you learned nothing of the danger of a desperate man? And with two children in your care! Throwing yourself into harm’s way for the sake of your mercy, as you would call it. Look where mercy has gotten you.

“We will stop here for the night,” said Maglor, untangling his hands from the children’s.

“But why?” one of them asked. With pain overwhelming his thoughts, Maglor struggled to tell them apart. “We went much further the other days, and it’s still light.”

“Yes, that is true.” Maglor rested a hand on the crown of the child’s head. Elros, this one, with his quick speech. “But I am recovering from the wound I suffered this morning. We will journey further tomorrow, hm? Do you see how the trees have grown thinner? That means we are nearly out.”

Elros puckered his lips and pulled them to the side. “I was sick and I got better,” he said.

“You did,” said Maglor, and stroked his soft black curls. A cough seized him, and a stab of pain sent him to his knees.

“Are we going to eat?” Elros asked.

The coughing fit kept Maglor from answering. He waved a hand in the direction of his pack, hoping there was still something in it they could eat. He did not have the strength to forage from the woods tonight.

“Come, Elero,” said Elrond. “We’ll find something to eat.”

Maglor willed the spasms to cease. “Stay. You cannot go off alone. There is—” he coughed, “there is food in my pack.”

“We won’t go where you cannot see us,” Elrond said. “We need more food.”

“Anyway,” said Elros. “What will you do if we are threatened?”

This made Maglor laugh. A welcome release, worth the pain and risk of aggravating his lung. “Very well. Sing as you search, won’t you? So I know you are not in danger?”

They nodded.

Maglor lay back, propping his head upon a stone and forcing his eyes open. Their song was not one Maglor had heard before.

'Twas in the Land of Willows where the grass is long and green—

I was fingering my harp-strings, for a wind had crept unseen

And was speaking in the tree-tops, while the voices of the reeds

Were whispering reedy whispers as the sunset touched the meads

Inland musics subtly magic that those reeds alone could weave

'Twas in the Land of Willows that once Ylmir came at eve.

Maglor smiled each time the song was interrupted with friendly disagreements on the phrasing and on which line came next. The song concluded, they seemed to forget why they had been singing and stopped; but their conversation carried on. Maglor listened to the pleasant lilt of their voices, paying the content no mind.

Then the conversation turned to him.

“What is wrong with him? He’s not bleeding.”

“Maybe it is like when you hit your head. He’s wounded inside.”

“He keeps coughing.”

“Do you remember when you almost drowned you kept coughing?”

“I didn’t almost drown! I got water in my nose.”

“Mama said you almost drowned.”

“Mama was always worried.”

They fell silent. The sweep of an owl’s wings whooshed somewhere up above.

“What if Maglor dies?”

“He says he needs to rest. Then he will be better. I rested and I got better.”

“But what if he doesn’t?”

“He is an elf. They cannot die like that.”

“His sister died after he had already healed her.”

A pause.

“Maybe we should help him.”

“How?”

“There must be a way.”

At this they stopped talking and a moment later picked up the song again.

They returned with two cloth sacks filled with wild carrots, garlic, and a handful of the summer’s last berries. Maglor carefully propped himself on his elbows and praised their industriousness.

“The carrots are better cooked but we can eat them raw,” said Elrond.

“Yuck.” Elros spat out a berry. “It tastes like soil.”

“Don’t waste!” his brother said, alarmed. “It doesn’t matter how it tastes, it’s food.”

Elros scowled and held the handful of berries out to Maglor. “Do you want them?”

Maglor would have laughed if a cough had not robbed him of his breath. “You eat those things,” he said when the fit had passed, “I will be well without food for some time yet.”

Two pairs of wide grey eyes stared at him, disbelieving.

“Please do not worry. I will be quite all right. You’ll see.”

He was awake through the night, not coughing but breathing too shallowly and painfully to find rest. The children lay on the ground beside him. They did not shy away when he draped an arm over them. Elros’ heart thudded softly against his chest, and the comfort of another beating heart soothed his pain somewhat.

Would they truly help him, if he asked? Could he find the will, the humility to ask it of them if it came to that? Would it be worthwhile? Whether he lived or died in the attempt, would the deed not haunt them for the rest of their lives?

If it were done, it would need to be done quickly and with courage. It would be better if he prepared them for it. They might well refuse, and then it would be decided; his survival would be left to chance. He might live long enough to get them out of this wood; he might even make it to Amon Ereb, where there were healers who could bring him back. Yes: he must believe it possible. It did not matter how unlikely any of it was; despair meant only certain failure.

Tomorrow he would do it. He would instruct them on how to save his life.

By the light of morning, walking to the tune of the children’s chatter, it was more difficult to imagine broaching the subject of death. Besides, his pain had lessened somewhat; though sleepless, his rest had helped. It may yet be that his body would heal itself.

In a moment of quiet, Elrond scurried up to walk beside him. “Maglor?” he said.

“Yes?”

A string of leather hung from Elrond’s closed fist. “I want to give you this.” He opened his hand to reveal a carved wooden pendant, a perfect circle engraved at its centre. It was painted with vine-like lines that reminded Maglor of the patterns the Penni inked on their skin.

“What is it?” Maglor asked.

“An amulet for protection.”

“Where did you get it?”

Elrond’s eyes darted to the ground. “Nelpen gave them to us. He said it would protect us.”

“Do you think I need protection?”

“Well, you are sick.” Elrond’s voice faltered and he fell out of step. “Maybe you can just borrow it until you are better?”

Maglor brought them to a stop. He looked from Elrond to Elros, both of them watching him expectantly. Were they truly concerned for him? He could tell them now. It would follow naturally. They knew something was wrong; they deserved to know what it was, and what might become of him.

“That is very kind,” he said. “I will return it when I am better.” He ran his thumb over the wood and its engraving. “This is a very special gift. You have good hearts, both of you.”

For the first time since they had left the Penni behind, Elrond smiled, revealing a soft dimple high up one cheek, close to his ear.

Every night, Elrond forced himself to stay awake as long as he could. He needed to know that Maglor slept. He needed to know that he was healing. But every night, he fell asleep first, and in the morning Maglor would be up, preparing food and packing their things for the day.

“Elves need little sleep,” Maglor told him. “I am resting, even if I am not sleeping. You need not worry.”

That was not true. Elves who were injured or sick needed to sleep. They needed to visit the Gardens in their dreams. That is what Círdan told them when a beam had fallen on his head. And Maglor kept coughing and clutching his chest. He was trying to hide it from them but they saw, just like they had seen when Mama tried to hide away her sorrow.

One morning, though, Elrond was woken by Elros jabbing a finger into his side.

“Is he breathing?” Elros whispered. Elrond was lying in between his brother and Maglor. He bent his neck back, keeping the rest of his body as still as possible. Maglor’s eyes were closed.

“Yes,” Elrond said, after ascertaining that the slow rise and fall of Maglor’s chest was not an illusion. “He is asleep.”

They shuffled out from under their blankets, ever so quietly so as not to wake their guardian.

Their packs ready, Elros lingered, staring at Maglor on the ground. The sun was climbing high and still he had not stirred. “Do you think it is safe to leave him? What if we get lost?”

“We are already lost,” said Elrond.

They set out on their own. Every hundred steps, Elrond left behind a colourful pebble to mark the way back. The forest did not seem so gloomy that day. The trees here were thinner, as Maglor had said, and many were losing their leaves, opening up the canopy to more light.

“These woods remind me of Nimbrethil,” said Elros.

“Those were birches,” said Elrond, remembering the woods full of tall white trees like pillars. Papa had built Vingilot from those trees. Everyone said it was the finest ship that had yet been built this side of the Sea — but it had not remained this side of the Sea long. It had taken their father away and never brought him back.

“I know,” said Elros, “but these woods are pleasant like Nimbrethil. It doesn’t feel so dangerous here.”

Elrond said nothing. A sombre mood had fallen on him; he did not like remembering.

They carried on, walking hand-in-hand but not speaking. Elrond kept his mind busy counting steps. He counted in Sindarin, then Quenya, then Hadorian. He struggled when he came to twenty in Hadorian and needed Elros’ help. He even tried counting in the tongue of the Haladin, what little Gwereth had taught them, but he only made it to five.

He was so occupied with counting that he was down to two pebbles before he noticed they were running low. “Elros,” he said, “we have to stop. We’ve run out of trail markers.”

“Oh.” They both looked about, assessing if they’d come any closer to finding the edge of the forest. “I think it looks brighter than way,” said Elros, pointing.

Elrond considered. “I think it is only that the sun has risen in the sky. It must be nearly noon. Do you think Maglor has woken?”

Elros pouted and hunched his shoulders. “I don’t know.”

“Maybe he will see our pebbles and come find us?”

“Maybe.” Elros sank onto a tree root and opened his pack. “I am hungry.”

They snacked on nuts and the starchy berries, dried out in the sun. Elrond took time to chew each morsel carefully. He felt more full if he ate slowly, and he told Elros as much but his brother said it was all in his imagination and too little food was too little food, no matter how long you took to eat it. Well, whatever the case, taking his time eating also delayed deciding what to do next.

Just as he was rolling up his satchel and fastening the buckle, a most unexpected thing occurred. The root they were seated on moved.

Elrond leapt to his feet. “Did you feel that? The tree moved!”

Elros stood, backing away. “It did not,” he said, but with such doubt that Elrond was sure he had felt it too.

“Enyd!” Elrond cried. He tugged at Elros’ sleeve. “You remember, I told you? Orfion said they were in this forest.” Fear swept aside by excitement, he set his palm against the smooth bark; or, rather, his skin. “Lord Beech,” he said, not knowing the proper way to address an Onod, and thinking this one looked most like a beech.

His sturdy base rumbled and shook, roots uncurling, drawing toe-like tendrils from the soil. Overhead, branches shivered, bringing to mind a man waking from slumber and stretching his arms.

Elros had retreated, and now hissed: “Elrond, come away! It could be dangerous!”

But it was too late to flee, even if Elrond had wanted to. The Onod was awake, and turning his amber eyes down on them. His long mossy beard wagged as he spoke. It was nothing like any language Elrond had heard, rumbling and deep and endless, but it was language, and whatever words were in it, it seemed friendly. Though the Onod had not the expressiveness of a human face, Elrond was sure that he was smiling.

“Hello, I am Elrond,” he said. “This is my brother, Elros. I am afraid I do not speak your tongue, but I do speak three languages. A bit of some others,” he added, for he had learned some of the tongue of the Penni while they stayed with them. “Perhaps you know one of them?” Then he repeated himself in all the ways he knew how.

“Hasty little sapling!” the Onod finally answered in Sindarin, the first language Elrond had tried. “Ho hum, barararum, yes, yes. I am…” He paused for a long moment. “Neldoremmen, yes, that is it, in your tongue. That is what the Elves called me. I know the tongue of the Elves. Elrond. Elros.” He looked between them. “What are two little saplings doing alone in the forest?”

“We are looking for a way out,” Elrond said.

“Out?” said Neldoremmen. “Ho-hum, two saplings seeking a way out. I have not been Out for a very long time. Hum-hum, barum, let me see, let me see if I remember…”

The panic brought on a fit of hacking, wheezing, a pinching of his lungs, a pain so great his eyes watered with it. Maglor had no voice with which to call for them. Gone! Had they fled? What a fool he had been, to think he had earned their trust. Of course they would flee, the moment the chance came. Ai, but he should not have slept! They had come so far, they were so near, and he had lost them.

It was the last strain his lung could take. He was abruptly overcome with dizziness, swooning, and rolled onto his back, each laboured breath like a knife. He groped over the ground, absurdly, thinking in his panic that if only he could find a bit of hollowed bark he could save himself. Absurd. His hand recoiled. What use was suffering when death was certain? He reached for the knife at his hip, struggling even to unsheathe it with how his limbs shook.

As he fumbled with the knife, trying to arrange it at his throat, he heard a voice. “Stop! Maglor, stop!”

“Elros?” he mouthed. “Elrond?” The knife fell from his hand.

“You’re dying!” one of them cried, and fell to his knees beside him. “Don’t die! Maglor, no! We found the way out, don’t die.”

It seemed to Maglor that he had been lifted upon a cold, roaring wave that he rode, suspended high upon its crest, towards his end.

“A hollow branch,” he instructed. “Narrow.” One of them ran off. The other kept wailing. Maglor shoved the knife into his hand: so small, cold and clammy with sweat. “Here.” He pointed to the space between his ribs where he needed to pierce a hole.

“I have it,” said the other child.

“You want me to kill you?” the one holding the knife said.

“No. No, a hole. A hole for the wood straw. Draw…” he breathed, “draw the air out.”

“It will hurt you.”

“No time,” said Maglor. “Now. Do it.”

He barely felt the knife piercing his chest. The child had a steady hand. “Enough,” he said. “Now the straw. Push,” he urged, even as the pain of the hollow branch breaking through his new-made wound overwhelmed him. “Your mouth. You must draw…”

Somehow, they understood. The trapped air and blood was drawn from Maglor’s chest. His lung filled, pressed against his ribs. He breathed, then the great wave of pain overtook him.

“He’s waking up!” A voice, frenzied.

Maglor lay on a bed in Himring; the dragon smoke had burned his lungs. No: He was laid out on a stretcher, swaying, each jostle aggravating the bones fractured in the great tumult of their retreat.

No — that was all long ago. This was some other time; some other dance with death. Do you feel a longing to escape, Maglor? He blinked, and at once squeezed his eyes shut against the intensity of the light. The sun battered him with its rays, but he was cold, so cold. And damp; his chest was wet. His fingers found the sticky coating of blood.

“I am sorry,” the voice said. “We tried to bandage it.”

A child? Why would a child attend him?

“Maglor? Are you alive?”

Maglor peeled his eyes open again, rolling them to the side to see the face of the one who spoke to him. He gasped.

“You—” he reached for the innocent face. Freckled. “Elrond. Where is your brother?”

“I’m here,” said the other child, who knelt just behind.

“So you are,” said Maglor. “So you are. Little stars.”

Who can say where the river will flow or the tree will fall? That had been the saying among the Penni. How strange the twists of fate. He was saved.

The twins were rapt with mixed horror and fascination as Maglor cleaned and sutured and re-dressed the wound in his chest.

“You did well,” he said. “Which of you was it held the knife?”

“Me,” said Elros. “Aerandir taught us woodcarving, I even had my own set of tools, even though Gwereth said it was dangerous to use knives, but I never cut my fingers…” He trailed off. “Will it be better soon?”

“It should heal quickly now that I have tended it.” Maglor locked eyes with Elrond. He had said little since Maglor had recovered. Small wonder: his had been the most gruesome task in saving him. No child should be subjected to such horrors. Even Maglor, who had seen and treated many hideous wounds, was yet haunted by them. It would be one of Elrond’s earliest memories: sucking from the dying body of the warrior who had taken him from his home.

For now, he was docile, processing. Elros was not so. He was eager to get on and buzzing with excitement over the knowledge they had gained on their expedition.

“So we can follow Neldoremmen’s butterflies soon?” he said. “It is only a few days’ journey, he says, even for our little legs. Follow the ones with brown spotted wings. They are his friends. They will take you to the forest’s edge.”

“Yes, so you have said.” Maglor had not meant to sound so tired. But he was tired. Now that his lung had healed and he could breathe naturally again, he was aware of other pains. His ribs had been fractured in at least two places, and his fresh wound throbbed angrily.

Before Maglor could muster an excuse for further delay, Elrond spoke for him. “I think we should stay tonight and set out tomorrow.”

“Why!” Elros cried. “There are many hours of daylight left. And it is safe in these parts, remember, Neldoremmen said, he and his friends would watch us.”

“Then we will be safe staying here,” Elrond said. Maglor recognised the signs of something passing between the brothers — not mind-to-mind, but in the simple way that all siblings could speak to one another: with a narrowing or widening of the eyes, a minute flicker of the mouth.

“Fine.” Elros crossed his arms over his chest. “But tomorrow at first light we are leaving.”

“An excellent plan,” said Maglor.

Butterflies were creatures of Irmo. His Gardens glimmered with the fluttering of wings, in hues a hundredfold. Maglor remembered, vividly, thousands of them blanketing the body of Míriel; how they had fled in a great cloud of colour when he and Atya and Nelyo approached. It was not the first time they had visited her, nor the last (though they went less and less), but it was this image Maglor recalled when he thought of his grandmother. Shrouded in butterflies. How strange, he had thought, with his boyish fascination with all aspects of the world; how strange that they all should land upon a vacant corpse when there were fragrant flowers all around. But they fled before Fëanor and his sons; dashed off in all directions, disappearing in the foliage.

Maglor was always sorry to have frightened them.

“There’s one!” Elros cried, and tugged at Maglor’s hand.

These butterflies they followed were brown and spotted black, scarcely to be seen against the bark and detritus of the forest. They fanned their wings sleepily as the three of them passed.

“I see it,” said Maglor. He winced and hoped the child did not see it. Every breath still pained him.

“I see another!” Elrond called from up ahead. “How much further, do you think?”

“Hmm.” Elros tapped a finger to his lips. “What do you think, Maglor?”

“How am I to know?” Maglor smiled at him. “Why don’t you ask the butterflies?”

Elros let out an affronted puff of air and his hand slipped from Maglor’s palm. He hurried to catch up to his brother.

Brown wings darted across Maglor’s vision. What if he had died? What if they all three had died, there in Taur-im-Duinath? Or were the two children skipping ahead but a vision, drawing him deeper, through the Gardens to the Halls? Halls from which he might never return. Ah, but would it not be welcome? Bodiless and aimless, yet confined. Unable to wander, unable to err. He shook the thought loose. He had not died; because of Elros and Elrond, he had not died. And for them, he would live.

They emerged on the southeast edge of the forest on a day of wintry rains. Beyond the cover of the trees, the ground was soaked through, great pools forming wherever the land dipped. Through the mists, the grey height of Amon Ereb appeared intolerably distant. Yet there it was. One steady foot before the other, and they would come to it by nightfall.

Maglor searched himself for a spark of relief and found nothing but the cold of his hands and feet and the ache of his ribs. The weight of Elrond and Elros propped under both his arms, shivering. There would be no relief until he saw them put in dry clothes, laid out on warm beds, asleep behind guarded walls.

He was half-sleeping on his feet when the riders found them.

“Ho there!” a voice called, and Maglor looked up from under his soaked hood.

The captain’s face paled. “My lord?”

Elrond stirred awake, turned his face to the stranger.

“Lord Maglor. You are alive. They are alive.” The rider’s dark eyes scanned them. “Where… where are the others?”

“Gone, Captain Lisgon,” Maglor said. “All of them gone.”

Lisgon shook himself from his amaze, turned to his small following. “Cruinil, go with speed to Lord Maedhros. Tell him his brother has returned. With the sons of Elwing.”

They were horsed and wrapped in warmer cloaks. Elros and Elrond refused to ride with any but Maglor and sat one before and one behind. Elrond’s head tucked into the curve of his stomach, drooping to one side to rest against his arm. The side of Elros’ face rested against his back, arms snugged about his waist.

Maedhros emerged from the curtain of rain, leading his horse behind. He held his head high but looked down and to the side.

“Leave us,” Maedhros said to his captain. Lisgon trotted off with his company following, leaving Maglor forlorn.

“I am sorry,” said Maglor. His whole body shook. The children stirred and tensed, turning their faces to the warrior who stood before them. “This is my brother,” Maglor answered their unvoiced question. “We are safe now.”

At last Maedhros lifted his face, pushed back his hood to reveal hair damp with rain and grown longer than it had been the last Maglor had seen him. He held Maglor’s eyes only a moment, then walked silently towards them. He helped the children down from the horse. They clung to each other the moment their feet touched the ground.

Maglor crumpled into his brother’s arms. The tremors running through him burst their bonds.

“Maitimo,” he said, “Nelyo, I am sorry. I lost everyone.”

His brother cradled his head against his chest. Maglor felt and heard the frightened drum of Maedhros’ heart, beating too fast, betraying the emotion he attempted to strangle with stillness and silence. Maglor’s chest spasmed painfully as the press of his brother’s hand on his head, his arm on his back, squeezed at the heart of his sorrow. Tears spilled from his eyes.

At last Maedhros spoke: “You did not lose them.” Elros and Elrond drew close; one of them cleaved to Maglor’s leg. “Dearest brother,” said Maedhros, breath grazing Maglor’s temple. He kissed it. “How I feared for you.”

For a moment, at least, Maglor brushed against a feeling he had not expected ever to know again. Even here, in defeat and disgrace, love seeped into the fissures carved by grief. Hope kindled.

The healers tended Maglor’s wounds. Maedhros came to him, now and then, and asked if he was recovering well. Quieted him when he tried to fill the taut silence with explanations and muddled accounts of his journey. “Later,” Maedhros soothed. “You need not recall it now.”

Only when Maglor rose from bed, hale enough to walk about the fortress and rediscover life within stone walls, life as lord of a shattered people, did Maedhros let his tears fall. He spoke of remorse. He told Maglor they would never again be parted, for they alone remained.

Maglor thought of the twin boys, wound together for comfort, sleeping on a nest of blankets by the fire in his own room, for they refused still to sleep without him near, and he thought: not altogether alone. Not yet.

Art by starshadeemily

Great was the sorrow of Eärendil and Elwing for the ruin of the havens of Sirion, and the captivity of their sons, and they feared that they would be slain; but it was not so. For Maglor took pity upon Elros and Elrond, and he cherished them, and love grew after between them, as little might be thought; but Maglor’s heart was sick and weary with the burden of the dreadful oath.

- The Silmarillion, 'Of the Voyage of Eärendil and the War of Wrath'

Chapter End Notes

Neldoremmen (“tangled beech”), Cruinil - From Chestnutpod’s Elvish name list.

Aerandir - Canonical, another of Eärendil’s crewmen.

Elrond and Elros’ song - From ‘The Horns of Ylmir’, a poem by Tolkien introduced thus: “Tuor recalleth in a song sung to his son Eärendil the visions that Ylmir's conches once called before him in the twilight in the Land of Willows.”

Maglor’s Injury - As I said re: Dornil’s injury, all the things that can go wrong with a body confuse me. I am not sure that what happens to Maglor would make it into a biology textbook. Maglor has a collapsed lung (pneumothorax) from the impact of Embor’s club; at first only partial and (because apparently Fëanorians love pretending everything is fine when they are fatally wounded) and becoming severe. While researching, I found this very interesting passage from a 13th century poem recounting a “tube thoracostomy,” which is what I followed in describing what is done to Maglor. Please, you need to read this:

He grasped a branch of the linden tree,

slipped the bark off like a tube–

he was no fool in the matter of wounds–

and inserted it into the body through the wound.

Then he bade the woman suck on it

until blood flowed toward her.