So You Want to Present at a Tolkien Conference? Putting Together the Presentation

The video and materials from our latest session of "So You Want to Present at a Tolkien Conference?" are now available. This session covers crafting a paper intended for presentation and designing helpful, accessible visuals to accompany your talk.

Home Alone: Forgotten in Formenos by Dawn Felagund

Chapter 16: Not a Brave Man

The poet’s wisdom will claim that a terrified rabbit grows so overcome by its panic as to become all but literally petrified: motionless in the face of that which threatens it, as easily plucked from life by a fox or a hawk as you or I would pluck an apple from a tree.

But the hunter’s wisdom will contend that rabbits are not so simple. That they will run and evade. Scream. And when pressed, they will fight.

The Ambarussa stand for a moment at the block in their father’s kitchen, petrified, yes—but just for a moment. They hear the plans of Iniðilêz and Dušamanûðânâz, for they are all but shouted outside their window, and swiftly their reaction is that of the rabbit: to flee, evade. To zigzag their way to safety. Surely someone in the town will take them in! They remember, briefly, that they are small and still delightful. They could make their eyes round and voices high and be taken in without question, and no one ever need know that they were forewarned of the theft of their father’s vault. In fact, they know, blessings will be counted that they were not home.

But the urge to flee and shriek for aid are as ephemeral as a snowflake on the tip of the nose. It is Ambarussa who, at last, speaks aloud what has stirred in both their thoughts, faster and faster like a sea-fed storm: “This is our House. We have to defend it.”

The twins are not yet the age when they will be pressed into deciding upon a talent to nurture. They enjoy all the playful whimsies of young children in a house of artisans, an admiration for colored pencils and xylophones with a rainbow array of bars and soft clays made of flour and salt, and they indulge in these in a dabbling, unfocused way permitted by their youth. Their drive—inherited in twain from their mother and their father—is swathed like their hands and cheeks in the softness of childhood. Maturity has not yet honed it.

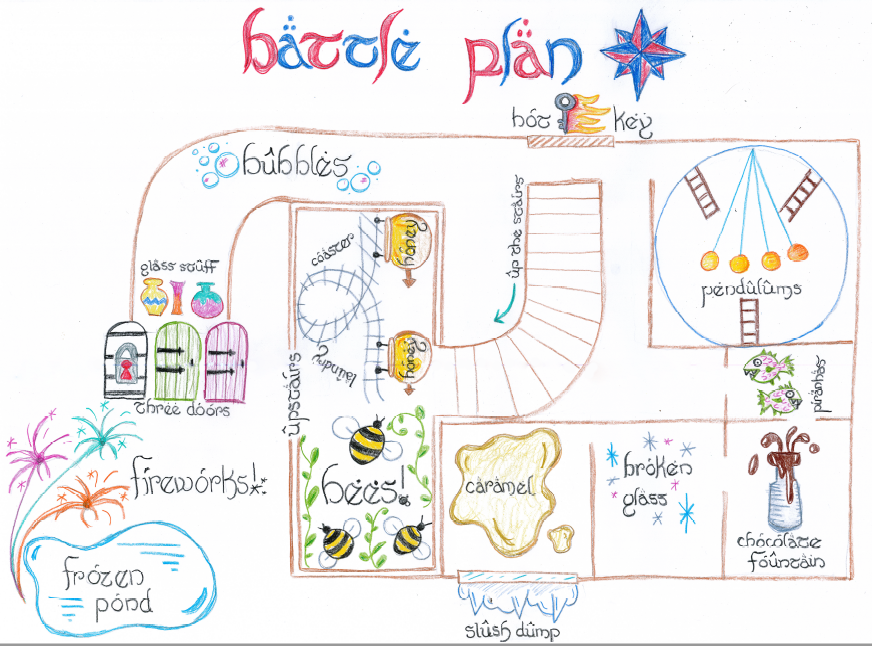

But present it is, and beginning to stir. They sideline the pencils and rulers on their father’s drafting table with a sweep of their arms. When Nelyo goes to the grocer in the village, he brings them what he calls “big paper” back, intended for cuts of meat but ideal for their sprawling imaginative drawings. They unroll and cut a sheet to the dimensions of the drafting table, and Ambarussa secures it at the corners while Ambarto hones their colored pencils with a tiny knife. And elbow to elbow, colored pencils pinched in their fingers, they bend silently to their task.

When their work is complete and they back away from the drafting table, they are delighted to perceive that all that they need for their plans is easily at hand. Such is the unintended advantage of being the children of craftspeople: Items which are poisonous and perilous and dangerous, honed, and hot are readily at hand, tucked alongside extra stores of soap or a dustmop or the rag bag of unmatched socks. Scurrying like a pair of ants through the warren of their parents’ house, they marshal what they will require. Only one thing is missing. Tremulously, they confer. Will they dare proceed without it? They will not; they will need to return to the village.

On this Yuletide eve, smoke from many chimneys curls like silvery quillwork against a woolen-white sky. Each cottage is frosted prettily, sparkling around the eaves in the late day’s light. There is a growing hush upon the streets as the people go in to their dinners, the candlelit windows casting rosy patchwork upon the snowy streets. The twins hesitate as they pass some of these windows, which frame scenes of conviviality and kinship: chortling delight as guests balance tottering towers of packages as they clasp in hearty embraces. Lively music tinkles into the street. Open doors exude the fragrance of Yule roasts and buttery pies and sweetmeats dusted with cinnamon.

Around the town’s small square, merchants are beginning to douse the lanterns in their windows and draw drapes across the festive displays glittering within. They are departing for their own homes and dinners. The twins observe with relief that the shop they need remains bright, even gaudily so, cocooned in strands of lampstones and with tall candles bristling in each window beneath a corona of fire. It is Ambarto, the careful, crafty one, who pauses outside the door. He has hidden a quill and scrap of paper in his cloak, and he removes them now. Ambarussa, drawn like a moth to the flame to the temptations of the shop, steps one foot across the threshold before withdrawing to wait, jostling in place, for his brother to finish scribing the note in a careful hand impeccably trained by Nelyo.

And then they go in.

The shopkeeper smiles indulgently. She is used to small boys perusing her wares with whispering urgency, darting from shelf to shelf, display to display, with a frantic, subdued joy. She is clad as a Noldo but with touches of oddity that reveal she comes from Taniquetil. Her golden hair is wrapped in a long, many-hued scarf; chips of bright gems march up her ears, each with a tiny glowing heart. The Ambarussa hold a whispered conference with each other; coins are counted and weighed against different possibilities until three rockets are selected from the shelf and brought in the boys’ small hands to her counter.

“Is he in tonight?” Ambarussa asks. He is trying to imitate the brazen confidence of his father, leaning one elbow on the counter (he is so small that the elbow ends up around his ear), as though inquiring as to the whereabouts of a Maia is regular for him. The handsome, youthful-faced pyrotechnician is a favorite of their father, and many afternoons have been wiled away in boredom-induced games amid the rockets and crackers and sparklers as their father and Olórin prattle about chemical reactions.

“Not tonight,” says the Vanyarin shopkeeper as she carefully records their purchases in her ledger. “It was his turn to cook our dinner.”

“But he is in town? He did not go to Taniquetil for the feast?”

“Not this year.” Her eyes have narrowed slightly, the look adults get when children show in inappropriate degree of curiosity. Ambarto, the more sensitive of the two, perceives a glimmer of misgiving in her eyes and steps in to supplant his brother’s place. Macalaurë himself could not arrange his face to be more pitiably innocent, or so Ambarto likes to believe. With wide, blinking eyes, he smiles up at the woman and proffers the scrap of parchment he wrote outside the shop.

“Would you give this to him, please?” The hand offering the note is tentative and unassuming, and the shopkeeper can hardly refuse, though she purses her lips in a mild show of disapproval.

“Would you like a bag for your purchases, my young lords?”

“We will use our satchel and thank you. We hope you enjoy your holiday dinner with the Lord Olórin.”

Outside, the light of Laurelin to the south of them is beginning to visibly wane. Ambarussa grabs his brother’s hand, fearing they have tarried too long; the silver hours are nigh, and they have much yet to prepare. Ambarto shoves the three rockets into their satchel as they hasten, puffing tiny mists of breath, back to the gates where they have left their snowshoes. Just three days ago, they would have whined help out of their mother or Nelyo; now their fingers make quick work of the tangle of buckles and straps.

The cold is deep, and the snow creaks beneath their feet as they run, breath coming hard, back toward the house that sits like a tumble of blocks just in sight of the town walls. Conscious that Iniðilêz and Dušamanûðânâz might be lurking in the violet shadows that reach for them across the snow, they keep close to the forest’s edge this time, weaving amid the small trees beginning to push up at its edges. Aspens, pale as bone, crowd close. The twins, in their haste, do not notice that the circumference of the boles expanding. Now there are birch trees, their papery bark peeling in strips colored salmon and soot, and maples laden with next spring's samaras. The branches clot overhead, choking off the last dribbles of light. They do not notice that the wide places between the trees form a sort of path, and the path leads them deeper into the woods.

Until they arrive in a clearing. The Treelight is blocked by the forest to their south, and the stars overhead seem brighter. Ambarussa has taken the lead, as he is wont to do, and when suddenly the trees fail, he stops so abruptly that Ambarto crashes into his back.

There is something peaceful about the forest that brings them to a halt, motionless except for the breath steaming from their mouths. Ambarto’s mind skips back to his mother’s embrace and the safety he used to feel when swaddled in her arms. The forest is like that. It rocks him and sings. Iniðilêz and Dušamanûðânâz, he knows instinctually, cannot penetrate here. The slender aspens behind them are formidable as a company of soldiers. Around the clearing, in a ring near to a perfect circle, evergreen shrubs grow, livid with fat red berries.

Suddenly there is a faint rasping sound, the sound of something being cut away in slow strips. Both twins whip in the direction of the sound. At the far end of the clearing, a silver-white head bends to a task, a stone blade in his hands. His flesh is so pale he seems to rise from the snow itself. He wears a tunic with sleeves that, despite the cold, come only to his elbows. As he straightens, Ambarto perceives that it is one of their father’s old tunics.

The Wight.

His milky gaze falls upon them. Both gasp, and Ambarussa’s arm flings in front of his brother in an instinctual gesture of protection. The Wight is tall, his limbs so thin that the joints swell upon them like galls upon a sickened tree. His face is graven with shadow, and Ambarto remembers what Tyelkormo said of him dying under torment. He wears the memory on his face. A stone blade dangles from his hand. There is no doubt that, within a matter of seconds, he could spider across the clearing and the blade would be at their—

“Tidings on the Yule,” says the Wight in heavily accented Quenya. The lines on his face melt into a shy smile.

“Huh?” Ambarussa’s flung-out arm droops a little in surprise.

The Wight crosses the clearing, not with the preternatural haste of a many-legged thing but with a gentle deliberation that calls to mind the growth of the forest itself: the rising of the trees from samara and seed, and the creeping encroachment of the forest upon the meadow. There is an inevitability to him. The twins’ mouths hang open; the winter air is icy upon their tongues. And that quickly, the terrifying shape looming from the shadows becomes, when closer scrutiny brings a measure of familiarity, just a heap of harmless fabric, something soft and comforting even.

“Ti—dings,” Ambarto manages when the Wight is standing before them. The tunic is definitely their father’s; the blade is crude and shaped of stone but sturdy and well-honed.

“Would you like to come to my tent? I just put on a kettle of wild apple cider.”

A minute later, each twin’s hands wrap a clay mug of steaming cider. The hide walls of the tent open at the top to vent the smoke from the fire that crackles merrily at its heart. Though firelit, the tent is somehow not dim or shadowed. The place seems very bright, and it is warm. The twins did not know how cold they were till now. Their hands and arms tingle and itch with the returning warmth. There is no furniture, but the furs piled upon the packed-earth floor are abundant and warm.

The Wight serves himself last, using a ladle shaped from leather. He casts a pinch of fragrant herbs upon the hot surface of the cider; when the twins take a tentative sip, the cider warms their bellies and the herbs suffuse heat through their limbs. The itching in their skin subdues. The Wight settles himself opposite them, and in the genial light of his fire, it is hard to remember what in his face they found terrifying.

He begins hesitantly. “When you see me,” he says, “you can say hello. You do not have to be afraid. I am here by the leave of your parents. I mean your family no harm.”

“Our … parents?” says Ambarussa, and by gentle degrees, the boys coax the Wight’s story from him.

Tyelkormo was not wrong when he claimed the Wight was one of the Avari, perished in the Outer Lands. But when Ambarussa blurts out the tale of his captivity by Melkor, the Wight laughs. “I did not even make it across the Hithaeglir,” he says, "much less to brave the terror of the Dark One, as your grandfather did." There is a slight pinkening of his cheeks—a blush, Ambarto realizes, if that can be believed! “I am not a brave man,” he confesses. “I quailed at the shadow of the mountains and retreated to Ambaróna. My life there was good. Safe. I had a wife. Two children—a daughter and a son. I awakened the trees there and heard what tales they told and learned the lore of the earth. It was a slow, delightful life.

“But from safety comes an ignoble death. I was fetching water from the river when I slipped and cut my hand on a rock. The wound festered, and my feä forsook my body. I died. My trees, they beckoned me, but there was a voice too, from over the dark waters … The voice promised I would reunite with my wife and children if I obeyed its summons. I could not abide in loneliness. I am not a brave man. I followed the voice.

“But when the Gods here remade my form, and I walked anew, I found myself in this strange land, separated from my family by the dark waters. I mean to go back to them …” But he trailed away.

“My father!” Ambarussa interjects. “My father knows the Telerin mariners, and they would likely lend or even give you a ship!”

The Wight shakes his head sadly. “Our people are very different. Your parents have been kind to allow me to abide on their land, but my kind do not use the metals taken by torment from the earth. We use only what the earth places at hand: stick and stone. I could not return to my family in one of the ships of your friends. It would be a betrayal of all I believe. But your parents have not left me without hope.”

He leads them out of the tent and to the shape he was working over when they arrived. It is a canoe, carved from a single fallen log, and beautifully adorned with carvings of the forest, his life. His marriage to a woman whose hair coils among the leaves. A tree clasped in friendship. Two babes delivered to his arms. A stern god, his hand firm upon the Wight’s shoulder. And a tossing sea with a canoe small upon it, all stitched into a single story by a backdrop of forest.

“The work is fine,” Ambarussa pronounces. Ambarto, silent, runs his hands over it, feeling no crack or failing to admit so much as a drop of water. “It looks ready! When will you leave? We will help you port it.”

The Wight shakes his head and fades back to his tent.

He is pouring another cup of cider when they follow, sipping at it plaintively. Ambarussa, ever bold, rushes forth to put a hand on the Wight’s shoulder. “Did you hear me? We’ll help! We’ll help you port it to the river, then out you’ll go to the sea!”

“That is the problem,” says the Wight. “The sea.”

Ambarto is gentler but just as eager. “The sea is easy to find! The river is right down in the village, and it spills into the sea. All you have to do is ride the current! Our father has a map; we’ll show you!”

“The problem is not finding the sea. It is sailing it.” A pause, then, “I am not a brave man.”

“But your family—”

“I should have taken haven in my trees, as I was summoned to do, as my people have always done.” He clasps his head in his hands.

“But you didn’t.”

“Yet I should have.”

The twins hesitate. They are unaccustomed to the problems of adults; these are conducted over their heads and do not seek their counsel. The Wight’s preoccupation with his past failing reminds them of their own petulant stubbornness that they enact when they wish for the attention of their mother or Nelyo or anyone kindhearted enough to coax them back to reason.

Ambarto reaches out a tiny hand to place upon the Wight’s shoulder. “You should have? Maybe. But you didn’t. And now you have the choice to return to your family or not.”

“And frankly,” says Ambarussa, “living in our father’s forest? Is not your best life.”

“But what if I die again?” says the Wight.

“What if you do?” says Ambarto, who cries as grazed knees but is suddenly bold about dying. “If you don’t try, you know you stand no chance of returning to your family. If you do try? Well, you might die. Or you might not. But you’ve died before, and you survived that, didn’t you?”

The Wight pauses, and the boys can see he is mulling over what they have said. But then he rises and holds the tent flap open for them.

“It is late,” he says, “and time for small boys to be in bed.”

But as they depart the clearing, Ambarto looks back and sees the Wight standing alongside his canoe. His hand trails it.