The Sandglass Runs by Dawn Felagund, NelyafinweFeanorion

Fanwork Notes

This story is set in Aman and so uses Quenya names:

Carnistir = Caranthir

Artaher = Orodreth

Findaráto = Finrod

Arafinwë = Finarfin

Artanis = Galadriel

Angaráto = Angrod

Aikanáro = Aegnor

Tyelkormo = Celegorm

Curufinwë = Curufin

Nelyo = Maedhros

Findekáno = Fingon

NelyafinweFeanorion requested, "Modern AU setting with Caranthir and Orodreth pairing. I do like complex characters and personalities. I like slow burn, friends to lovers, relationship complexities, first times, quiet moments, mutual pining, developing relationships, mild conflict, hurt comfort, situational relationships."

This story is part of my Republic of Tirion series, in which I am reembodying the Noldor into the Fifth Age, where Finarfin has unkinged himself and (against the wishes of the Valar) turned Tirion into a representative democracy. You do not need to be familiar with the rest of the series to understand this story.

Fanwork Information

|

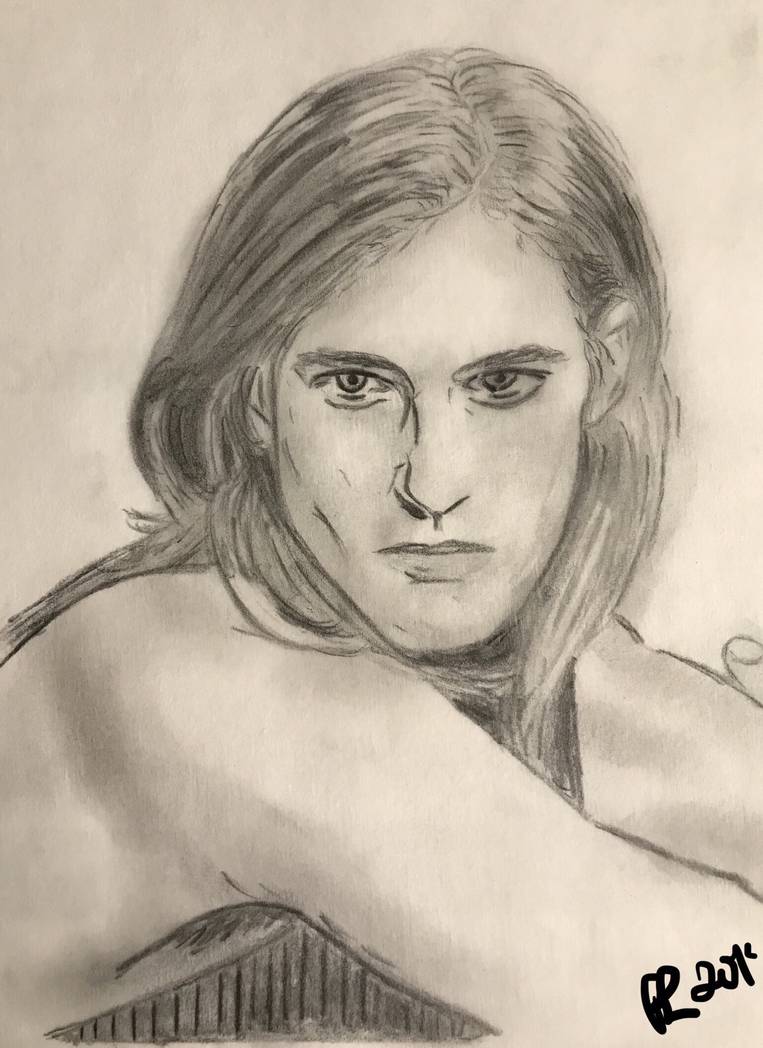

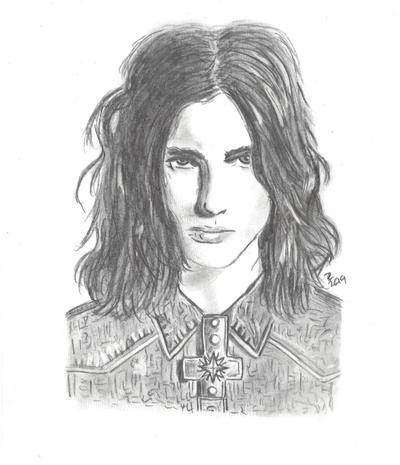

Summary: In Fifth Age Tirion, Caranthir has been reembodied into a changed world: his uncle has unkinged himself and turned Tirion into a republic, Elves live in suburbs and seek psychotherapy, and the Noldor born after his exile have invented all kinds of wondrous things. One day, Caranthir receives a letter that he is being entrusted to mentor his newly reembodied cousin Orodreth. They must not only resolve their old enmity but achieve a tenuous friendship--maybe even more?--as both seek the peace and acceptance they never found in their prior lives. Written for TRSB 2019, based on the artwork by NelyafinweFeanorion. Major Characters: Amarië, Caranthir, Orodreth Major Relationships: Caranthir/Orodreth, Amarië & Caranthir Genre: Drama Challenges: Rating: Adult Warnings: Character Death, Expletive Language, Mature Themes, Sexual Content (Moderate), Violence (Moderate) This fanwork belongs to the series |

|

| Chapters: 15 | Word Count: 23, 781 |

| Posted on 18 July 2021 | Updated on 19 July 2021 |

|

This fanwork is complete. | |

Family Therapy

Read Family Therapy

I hate family therapy.

I hate family therapy more than any other part of reembodied life. More than my job. Certainly more than individual therapy, as intolerable as that also is. Even more than the occasional guilt-induced lunch Uncle Arafinwë invites me to and my mother and Nelyo force me to attend. I thought I was mostly rid of it—family therapy that is—because I've been reembodied second longest of my dead family, and I think they've largely given up on me by this point. I don't think it's because I've made progress. I refused to go to any therapy for a long while, and when they tried to force the issue by using language with a vaguely threatening connotation, I remember yelling, "What are you going to do, shove me back in the grave? I didn't even have a damn grave!" Instead, they reembodied Nelyo, and I got swept into attending his family therapy because my loyalty to him, it seems, is in the germ of my being, and I didn't want to make trouble for him, even when it became clear that the focus was more me than him, which I think was a shortcoming on their part. Nelyo hasn’t turned out exactly well-adjusted, post-reembodiment. He wouldn't have suffered if they'd let me be and lavished their attentions upon him instead, who probably would have used it and maybe wouldn't look so pale and exhausted now.

I hate family therapy. I'm sitting in it now. I received the letter the other day. Letters used to come on parchment the color of tea with cream; they used to dance with calligraphy and kindle with gold leaf; they used to have wax seals that it was satisfying to break and come via messengers on fast, panting ponies; they were, in other words, special. Letters come now on white paper and in white paper envelopes, sealed with spit and delivered by postal address and a mail carrier who plods through the same route each day. This one wasn't even written to me. It was a form letter—another efficiency developed by ambitious Noldor for my uncle's republic—which I knew because they'd written in my name by hand, in blue ink, and spelled it wrong: Carnister. Thus, insult was added to injury.

Now that I’m here, though, the form letter makes grudging sense. I like efficiency, perhaps more than I like beauty even, and they weren't kidding when they said "family therapy"—the whole family—the whole family that is alive anyway—is here. That much calligraphy would have taken hours. There's my mother and Uncle Arafinwë and Aunt Eärwen, who forsook their various quasipolitical reparative projects to be here. Aunt Anairë, who took a day away from the House of Scholars to be here. Nelyo, off for the day from teaching (and sighing over how long it took to make sub plans) and Findekáno, who is maybe the only one of us not missing something important, come to think of it. Findaráto, away from his burgeoning political career in the suburbs at the Calcirya. Even Amarië is here, and she is doing an important performance art piece, although she's very much still at the wild-waving-around-and-shouting-while-holding-a-drink-in-a-bar stage of the creative process. Even Artanis and her husband what's-his-name are here! Over from Tol Eressëa, where they own the island's largest resort and planned living community. Scheduling surf lessons and balancing swimming pool chemicals are enough of an undertaking, apparently, that even intellectual and martial giants such as themselves can rarely get away. And me. I had to take the day off of work, which is no great loss for my job or for me, but I'd rather be there than here for sure. We are sitting in a big circle with my (our?) therapist between Arafinwë and Amarië. Her spiral notebook is open on her knees; multiple pens and pencils spear through her bun. "Should we start with introductions?" she says.

"Um," I remark, and Nelyo—who is sitting next to me on one side—pokes my foot with his toe right as our mother, who is on my other side, lays a hand on my arm.

So we pass around a talking piece—a glittery stone that my father would have thought too garish and puerile for an infant's toy—and introduce ourselves to each other, we who have gone to war together, gone on holiday together, eaten together, slept together, fought together, fucked together, seen each other naked, seen each other born, in some cases, for the love of Eru (this is why I can't stand this shit). "Carnistir," I grunt when it's my turn, "or maybe it's Carnister now," and, when encouraged to answer a question from the card she passed around to each of us, follow up with, "Pass."

I hate family therapy, but I have mastered using their own rules and loopholes to make the experience as unbearable for them as it is for me, at least.

Uncle Arafinwë speaks the longest, answering the question, "What treasured memory is awakened by the faces you see here to support you?" to wax sentimental about watching our family grow in the years before the Darkening and watching it grow again, gesturing expansively as he speaks. Never mind the small point that many of us assembled here had to die in order to favor him with such a joyfully symbolic experience: Here we are. At last, he shuts up, and the therapist continues.

"I have asked you here today on behalf of the Department of Judgment.” (This is what Arafinwë's government has renamed Námo's halls.) “I am most pleased—most pleased, truly—to be the one to announce that another of your family has been selected for reembodiment." Her face gleams with enthusiasm. I almost feel sorry for the lack of reaction she draws from us.

"Whom," my Aunt Anairë says at last, "should we expect?" and Findaráto—who also aspires to a seat in the Noldorin Congress and has cleaved to her like a tick to a dog—follows with, "And when?"

The therapist's smile wilts a little. "Unfortunately, that is not information that is shared with me."

"Oh hell," says Findekáno, and now it is his turn to be nudged by Nelyo. "Why do you do this, then? Call us all here for what amounts to nothing?" He sneaks a glance at me. We are unofficially allied as the most pointless of the reembodied Noldor and the most flagrantly difficult to manage.

"I don't like to think it's for nothing," says the therapist. "After all—"

Artanis and her husband are already gathering their bags.

"How does everyone feel," the therapist is trying to rescue her session, "about the news that you are about to gain another number? Arafinwë? How—"

"Do we even know which household he—she—they are coming from?" Anairë asks in a voice carefully constructed to be pleasant.

"Of if it is a he or a she or a they?" says Artanis at last in that voice deep and subtly threatening as the sea.

Arafinwë, who was winding up into another speech, is left open-mouthed, cut off by his female relatives.

"Unfortunately, I don't—" and the word unfortunately isn't even all the way out of the therapist's mouth before Artanis and her husband (Celeborn! the man's name is Celeborn!) are rising and beginning to converse with each other about the capacity of an excursion trip out to see dolphins and whether they should increase the thread count in the sheets they use in the villas.

"You should," Findekáno tells Artanis. "Nelyo buys those cheap sheets, and they're dreadfully itchy." He's standing as well, stretching to pop his back. Nelyo is checking the time and muttering about time to grade papers since he already hired the substitute teacher for the day, and our mother is asking if he can spare an hour to get lunch, and Anairë is standing and checking her planner to see if she can make the appropriations vote scheduled for later this morning, and that is the tipping point that makes everyone else stand except Arafinwë, whose lips are still parted and ready to give a speech.

"How about you, Carnistir?" my mother asks. "Would you like to do lunch?"

The therapist, to her credit, has accepted that she has lost the room. I think sometimes about how she is a government employee, like me, except that she answers to Arafinwë's government and Námo Mandos/the Valar, and that makes me feel a little sorry for her. I never believed, however, that her commitment to this job is as unenthusiastic as mine until now, watching her eyes dart toward the door as she considers whether our exodus is foregone enough that she can also head out for an early lunch. Well, maybe not as unenthusiastic, but she clearly doesn't have the personal commitment to this work that I'd always assumed when I was the subject of her particular and regular torment.

As though she can sense me thinking about her, her eyes catch mine, and something like recognition sparks there. "Carnistir! I'd like to see you privately for a moment before you leave."

“Fuck,” I say loudly enough that Artanis’s husband gives me the kind of look you’d give a hibernating bear that has just stirred in its sleep.

My mother and Nelyo suddenly become sluggish and excessively deliberate in gathering their belongings to leave. They are hoping to be invited too, both anticipating that I will cause a row if left alone, but the therapist pointedly avoids their questioning looks, fixing her stare on me, until they leave. “We’ll meet you outside,” says my mother pointedly, as though drawing attention to their presence might elicit the invitation they want. It doesn’t.

“I won’t keep him long!” my therapist calls. We both watch them leave. "We are beginning a new program at Lord Námo's entreaty," she begins.

"Bugger!" is my reply. I seem to be always selected for their attention.

"It is not a therapy program," she says. "It is a mentorship." She waits for my questions, but I won't give her the satisfaction. "You will be paired with this reembodied relative to offer guidance and support."

I laugh.

I don't know that she's ever heard me laugh. She looks startled. But it seems the only reaction that such a statement deserves. I'm barely functional in this body. I have a job, but I hate it and do the minimum to get by. I invent things at home that I never share or want to share. I play horrible, discordant music with Amarië that she views as part of a radical aesthetic, but I just like fiddling with wires and making noise. My mother invites me to dinner every week or two; Nelyo less, but he does invite me; I might as well not exist to the rest of my family except when Arafinwë gets a guilt pang and buys me lunch. I have refused most of the counseling and programs offered me by both the Valar and my uncle's government, even when told they were requirements; they haven't shoved me back in the grave yet. And even though I was dead for the better part of four ages between this life and my prior existence, this existence has really become a continuation of my first embodiment, and by design. No one outside my immediate family really liked me then, and none (Amarië aside) seem to really like me now. And this is because I cultivate the reputation of being dark and weird and unpleasant. I see it as a fence. (I told this to Nelyo once when he complained that I should make more of a point to be friends with Findekáno and I was a little in my cups and so susceptible to embroidering my thoughts with metaphor.) A fence is something that any farmer will be careful to mend and maintain because it keeps his livestock in but also keeps the interlopers out. This is my fence.

I am no way prepared to guide another soul through a new chance at life when I've plopped myself down on the road and already given up. Even if I was, there is nothing that could interest me less.

Intuiting my objections, the therapist goes on. "You were chosen, according to the Department of Judgment, because your particular proclivities align with those of the reembodied fëa." And I laugh again.

No one aligns with me.

QUIET CAR

Read QUIET CAR

They used to release feär from Mandos and let them stagger through Námo's creepy forest until they found their way or died and returned to the Halls. I don't know that the latter ever happened, but having made that journey myself, it is hard to fathom that it never did. Perhaps that's why they installed the metro system between Ostonúmë and the Halls: because rehousing a body is no small investment of time and energy and straight-up horror, and it's a shame if it expires a week later because, after all the test-tube flesh and haunted-house contrivances, it can't find water in a forest constructed of curls of ash.

A letter arrived the other day—plain white paper in a plain white envelope delivered at the usual time—utterly unspecial—and told me that I’d be expected at the halls of Mandos today and to take the metro from Ostonúmë. I had no idea what a metro was—have no idea until I descend a flight of stone steps under a bright blue M that was helpfully pointed out by a village resident. They have cashed in on the flow of reembodied Elves here in Ostonúmë: the streets are lined with clothing shops, therapist's offices, taxi stands, and information kiosks a lot like the one where I work in the Tirion Public Building except that the people seated behind them look like they actually want to help and even call to passersby in the street. I don't think I've called to anyone besides my wife, maybe to ask her if she can bring in a couple of those fresh cookies with her when she comes to bed. I don't generally entice others to associate with me. And they charge money, which I’m not allowed to do. (Not even allowed to have one of those tip jars that seem to have flourished everywhere else.)

At first, the metro is unimpressive: a pair of parallel tracks a lot like what Curufinwë and I used to build and use to race wooden horses fitted upon them. There is a humid, slightly unpleasant underground smell. A pair of Elves stand at either end of the platform where I assume we wait for whatever device will come along the tracks—I imagine it is going to resemble the wooden horses of my youth—and don't seem interested in interacting. That much about this "metro" I like.

But when the train arrives, I must admit that I stop short for several seconds. It comes like a gale through the trees, silver and sleek as a wave before it tumbles to the shore. I stop short for several more seconds, watching the other Elves to see what I must do. Doors slide silently open and expel several Elves; I recognize one wearing the grayish silk garments given to the newly embodied, attended by two chestnut-haired young women who can’t suppress their smiles.

That stops me short too. I do not think of Taryindë often and think of our daughters even less but these two young women and the obvious adoration of the man I assume to be their father—well, it's useless to go on. Findekáno once likened Námo's decisionmaking to flying a kite in a storm: predicting where the kite would crash—who would emerge next from his Halls—involves a welter of wind and rain that tosses in no discernible pattern. My mother said once that one must live as though the one most wanted would follow Míriel's fate, and she would know better than any. Taryindë was still in the Halls when I left, and our daughters had neither entered nor—I discovered once reemobodied—taken ship from the Outer Lands at the end of the Third Age. I expect to never see any of them again. I tell myself this firmly every day.

I certainly don't expect to see them today.

I don't.

But if there was a—

No.

I don't.

The passengers of the metro having disembarked, the two other Elves on the platform hasten forward, and I realize I should follow, so I proceed to the nearest open door. QUIET CAR, announces a sign over the door in paint the color of organ meat. The seats inside are the gray of falling rain and have a fungal squishiness to them. Clearly, the substitution of the metro for the long walk from Mandos has reduced the risk but not the ghoulishness. I am alone in the car.

The doors slide shut, and the metro whispers along its tracks. When we left Valinor in the vanguard with my father, we expected we were taking all the significant talent with us. We imagined leaving Valinor bereft, languishing in its past glories that the Valar would have to fight to keep from the decays of time. We didn't consider the Noldor born after we left, as curious, clever, and ambitious as our people had ever been. One of those ambitious youths had designed this metro. I wish I had thought of it first. It slips into the earth—I feel my ears pop—and misty red lanterns occasionally flash past on walls of dark gray stone. I wonder about its design instead of wondering whom I've been selected to meet. I wonder how it is powered. I can feel the speed of it, a feeling like my stomach is being pressed into my spine.

And then it eases to a stop.

The hazy red lanterns flash by slower and slower, and the pressure of speed against my solar plexus lessens. The complete cessation of motion is too slight to be detected; I know we've stopped only because the doors slide open again.

Námo's servants await in a small huddled herd on the platform. I remember them—their gray raiment, their sexless faces drawn with sorrow, their constructed smiles—from my own reembodiment years earlier. They cheer at our arrival, but their cheers are unsmiling and their pumping arms do not lift above elbow-level. Three do smile and come silently forth, one for each passenger, if the mere baring of teeth can be counted a smile. (Having used it myself many times, I do count it as such.) There are no words, no inquiries. They know instantly the contents of our minds.

One takes my arm with hands dry and powdery as cheap paper. We are walking down a brick-lined corridor; posters adorn the walls every few steps, advertising services for newly embodied feär. I recognize Arafinwë’s hand in that. The Elves depicted in lifelike detail are all in smiling crowds with the pomp and majesty of our previous monarchial system replaced by the sharing and laughing and conspicuous collaboration of Arafinwë’s republic. I am thinking that, were I not being escorted by a Maia of Námo, this corridor would be a perfect place for street art, and I am wondering if it is possible to access it without an escort and planning to tell Amarië about it to see if she knows an artist who is interested—she will find some profound political meaning in it; I will just enjoy breaking the rules right under Námo’s nose—and

We’re no longer in it. The corridor I mean. I don’t perceive it happening, but the bricks are gone, the posters, the tile floor beneath our feet. I am not that long reembodied; I should recall that space and time do not operate under the same constraints here as the rest of the world, Námo having abstained from the part of the song where those particular laws of physics were sung into being (or so the wisdom claims), but these laws are such an unthinking part of our world that it startles me nonetheless. The corridor around us is plush and gray. When I resided here, I felt like I was being slowly digested inside the ashen intestines of Námo himself. My inability to rid myself of such thoughts while I was here—and not because Námo didn’t do his best, and not because I didn’t want that “best” to cease as quickly and thoroughly as possible—is why I do not understand how I came to be reembodied second of my vast, dead family, second only after Findaráto, for the love of Aulë.

To our right, a door has relaxed open. A passage might be more accurate; it reminds me of a sphincter. I don’t want to go into it, but then I’m through it and in the room beyond, which—thank the Wise—actually looks like a room, with sterile white walls and tight, precise corners. There is a cot in the middle of the room. I recognize it, having been awakened upon one myself not that long ago, my throat the same bleeding ruin it was when I died as Námo worked to repair it. (I’m certain he awakened me early on purpose and took his time mending the wound while my new nervous system received its introduction to pain and terror.) I realize that my heart is pounding. There is no evidence of such bloody work this time. Námo was kinder to the figure on the cot than he was to me.

(I want to reiterate that I never expected Taryindë. When I met her in the Halls—she died protecting my unconscious body in the Nirnaeth Arnoediad—there was a shadow about her, and she would flee when I tried to touch her. Her body was never recovered. I’d hoped for a swift death for her. I never believed, though, that even the hope of joining me in a new life would rid her faster of that shadow. That would have been what Curufinwë liked to scornfully call a “fool’s hope.” I never indulged it.)

The figure on the cot is golden-haired. His back is turned to me, his body clad in the gray silk garments they put on new bodies to protect their new skin, which is tender-almost-raw for the first few days after reembodiment. He could be any one of my cousins.

A Maia manifests from the far wall. He/She (It?) holds out a hand to the figure on the cot. When the figure doesn’t move, she/he/it crooks fingers in a beckoning motion. The figure pushes at the cot with his palms, then cries out wordlessly; the pressure hurts as though applied to a new wound. I remember this. The Maiar holds out both of its hands, and the figure rises on the strength of his legs alone, trembling like a newborn colt.

He turns.

Artaher.

He is no more pleased to see me than I am him. No one was here when I woke up, nor Nelyo, nor Findekáno. Arafinwë apparently attended Findaráto’s reembodiment; given that Findaráto was the first of our family to be rehoused and the Valar regard him as especially exalted; nonetheless, forcing a father to watch the repair and reanimation of his son’s body that was mangled by werewolves seems the opposite of a privilege; perhaps it was intended as a statement on Arafinwë’s political experimentation? No matter—I am a father myself, and even for Námo, that “honor” seemed especially cruel. It seems, in any case, that Arafinwë did not merit a second invitation. I’m still not sure why I did.

I feel Artaher reach for my mind, but that is one lesson I was grateful to learn from Námo, and my thoughts and emotions are no longer as available as a bowl of fruit left out on the counter with the choice pieces ripe for the taking. I click my thoughts closed. “Not anymore,” I snap, and Artaher flinches, and so within seconds, our relationship has picked off right where it left off.

And then we’re sitting on the metro again, in the QUIET CAR again, although I’ve realized this time that every car is marked as the QUIET CAR, and I am using that as a pretense to not have to talk to my cousin. I can sense his discomfort—both the physical discomfort of his new, raw skin and the emotional discomfort that I, of all people, was the one sent to fetch him, and he is left to spend his first uncomfortable moments facing what his father, at least, insists is one of his greatest regrets of his previous life.

Chapter End Notes

With thanks to Archon Bun for the name Ostonúmë.

Lichen

Read Lichen

“It is one of his greatest regrets, what was done to you. I know it is.”

Arafinwë was eating a salad piled high with fruit and almonds, and fastidiously poking at the array of toppings with his fork gave him ample pretense to avoid looking into my eyes. I was fine with that; I was eating a slab of roast venison, and concentrating on sawing at it with a knife gave me a pretense to avoid looking into his. But when he pronounced this, he abandoned trying to spear a blueberry to look up into my face.

I hate the blue eyes in the Arafinwion line. My brother Tyelkormo had blue eyes, but his were dark and guileless whereas the Arafinwions? They were pale and piercing and beautiful and terrible. You know how when, on an overcast day, the clouds break just enough to let a beam of light spear the sea? They were that color. It was hard to look away.

I was enduring one of what I’d come to term Arafinwë’s “guilty lunches.” Once a year or so, Arafinwë insisted on inviting me out to lunch at one of the mediocre restaurants he loved, where he’d pour out his regrets where I was concerned. It seemed, upon receiving news of the Outer Lands as history brought back after the War of Wrath, he viewed certain events involving me and his sons as something for which he was partly to blame. And he was. These lunches were not an opportunity, in my mind, to offer consolation much less forgiveness; they were a chance to order the best, most expensive thing on the menu (often not very great, even if expensive) and enjoy my free lunch while trying not to relive much of what he was self-flagellating over.

This particular lunch had been about Artaher. Mad with pride at its democratic experiment, the historiographical establishment in Tirion had decided that Artaher was the Arafinwion most like his father and a hallowed innocent somehow swept up in the exile and journey east. Otherwise, he’d have been a republican and revolutionary, right alongside his father. Pictures of him in the history texts tended to show him loose-haired and soft-eyed, beatifically unsmiling with a suggestion of suffering in the lines of his mouth. Those who hadn’t come east tended to drop those of us who had into one of two bins: the rabble-rousers and the passengers. The rabble-rousers included all of us (Fëanáro’s sons), Findekáno, and Írissë. The passengers were Nolofinwë, Turukáno, and all of Arafinwë’s children—they all wanted something concrete in the Outer Lands but had maintained certain ethical lines they refused to cross (whereas, I suppose, the rest of us danced across them with impunity). Artaher, though, was his own category, and historians couldn’t seem to agree whether he’d been simply passive in coming along with the rest of us or if his attendance was to be read as an act of resistance. No matter where they came down, though, they all saw him as soft and pliant—essentially harmless.

My memories of him were more complicated.

I wasn’t born with many gifts, but I was exceptional in mindspeak. It came from my grandfather Finwë, skipped my father entirely (whose perception of other’s thoughts and feelings could be summed up as “blissfully ignorant”), and then pooled entirely in me, out of all seven sons, the way that rainwater will collect at the lowest point in a plain. None of my brothers had it. Just me. I suppose, lacking all other gifts, something had to arise. “Nature abhors a vacuum”—I remember that from Nelyo’s science lessons when I was still a boy. Even in lightless, rocky crags, lichen flourishes. Among an exceptionally gifted and storied people, I was that vacuum—at best mediocre at both scholarship and forgework—and so the mindspeak flourished within me. I never thought of it as anything but a curse.

Arafinwë is a case in this point also. Likewise painfully mediocre when compared to his two elder brothers, he received the entirety of the “gift” of mindspeak from Finwë, and he passed it on to all of his children in some measure.

That meant that, among the grandchildren, I had it, and Arafinwë’s children had it. No one ever bothered to tell me what it was. I assumed that everyone experienced other people the way I did: as a roar of color and texture that scintillated and prickled and furred with their emotions. I did not assume myself abnormal; it was much later that I realized the depth of my deviance. But my mind was wide open to it all the time. When people were at peace, it wasn’t bad—I remember sleeping in Nelyo’s arms, awash in his blue, cool like silk—but when others suffered even minutely, it was like having my eyes taped open and being forced to look at wounds. As my family disintegrated, the wounds deepened and festered. I was powerless to look away.

Arafinwë, naturally, taught his children better than my parents did. To be clear, I don’t blame Fëanáro and Nerdanel; they knew I was strange but had no notion why. Perhaps Finwë could have helped me, but he’d entangled himself too thoroughly in his own bad choices to spare much time for any of the grandchildren. At times, he would reach out and soothe me, but he never taught me to control it or—blood of Varda—shut the fucking thing off. Arafinwë’s children, though, not only controlled it but mastered it like any art, under their father’s tutelage.

And what I didn’t know? Until it was too late? That I wasn’t just receiving the emotions of others; I was broadcasting my own—and most of my deepest, most intimate thoughts—as though through a megaphone, to anyone who cared to listen. The thoughts of a young, troubled boy weren’t of much interest to my grandfather and Arafinwë and other adults who could have heard them if they’d chosen, but to my cousins? It was like I left my diary open on the kitchen table each night and invited them to read of me.

Findaráto couldn’t have cared less. Though younger than me by four years, as a firstborn son, he was coaxed and cultivated in all that he did. By the time we were adolescents, I already had the sense that his station was above mine, as a fourth-born son and an unpromising, unusual one at that. And he was the hope of the three Eldarin kindreds: the brilliant convergence of the three rays of each kindred, like the heart of a star; a sickening metaphor, but if you’d seen how people went doe-eyed at the mere mention of his name, you’d know it necessary sentimentalism. Though younger than me, he felt older—and inaccessible. Artanis was too young, at first, and later glommed so thoroughly onto Írissë that I wasn’t worth her attention either. But my middle cousins?

My middle cousins.

Artaher, Angaráto, and Aikanáro.

They were cruel to me.

As insipid and sentimental and stupid as Arafinwë can be, to his credit, he has never shied from empathy and the truth that empathy can reveal. When word reached him of the conflicts between me and his sons—a groundless conflict I’d initiated, as the histories were careful to note, for there was no reason for me to hate the sons of Arafinwë—he didn’t take them at their word that such incidents were entirely unprovoked, and I suppose he has had four ages since to look back on the social dynamics of our adolescence and young adulthood, conducted largely out of sight but surely not entirely unobserved, and eventually, he came to his own conclusions.

“In retrospect, I see that I should have done more to teach you.” He always led off with this. “To control it. Fëanáro had no way to know—even Nerdanel. Her gifts are differently oriented.”

Arafinwë has stewed on this for four ages. My stay in Mandos was agony and indignity, but if I came away with one thing of value, it was the teachings that none would give me in my youth. I kept my mind closed now. But made an exception, once, at one of our lunches so that I could perceive the depth of his guilt. If only he’d taught me, maybe? Maybe I wouldn’t have become Caranthir the dark.

I let my mind snick shut.

“I know they were not always kind to you.” They were never kind to me, but I left it alone. “Angaráto, Aikanáro … I accept their role in what happened … after.” He munched contemplatively on a bite of lettuce; I could hear his teeth crunching and disciplined my face not to look disgusted. He swallowed. “But Artaher … he had his own … struggles. Maybe you know? My father insisted you were the most perceptive of all of them. Artaher was next. He was tenderhearted; he wanted to belong. He followed where he never should have gone.”

And then the killing stroke: “It is one of his greatest regrets, what was done to you. I know it is.”

Batten Down

Read Batten Down

Which brings me to now.

I don’t have to worry much about what my mentoring duties of Artaher will look like because, as soon as we arrive in Ostonúmë, we are met by an entourage of his family—Arafinwë and Eärwen and Findaráto—and they pet and console him and ask little mewling questions for the entirety of the interminable carriage ride back to Tirion. I decide I don’t care. Námo himself could insist that I must mentor this flop but that doesn’t mean that I will. I’ve violated nearly every rule they set forth for me when I had my own turn sitting, trembling and afraid, the touch of mere air on my new skin like passing my arm too low over a gout of steam, on the cot in Námo’s halls, naked except for a silken shroud. In that moment, I’d been certain of my obedience; I hadn’t factored on how absurd this new world would be.

I stare out the window and try to ignore the hushed meep-meep-meep of conversation that reminds me of infants and crèches. Actually, I could never dignify myself to even talk to my daughters in that way when they were small. Valinor used to be mostly empty beyond its few glittering cities and Aman certainly was. The Valar used to make maps that conveniently faded at the boundaries of their authority, even though there were people and villages in those hinterlands. But Valinor is empty no more. Even Aman can no longer go unmapped. Every road brings a march of shops and houses that thicken as we approach a village. Villages used to convene upon the main road with spur roads off it like branches on a tree; these roads would quite literally fade into the forest or prairie at their ends. Villages now are senseless clots of roadways and shopping blocks and one-way streets and apartments and pedestrian boardwalks and traffic control; the roads bend and buckle back into each other—nothing simply ends here—so that there is a constant flow of new carriages trying to join the existing stream. Every one now is outfitted with absurd little rubber horns ostensibly intended to signal other carriages but usually used to rebuke those who slide into a gap not quite large enough that forces the driver to pull up short on the reins.

wa-HONK

Artaher flinches, and I feel a flash of pity for him. Back when I was reembodied, when the Eldarin people were still unprepared for such an eventuality, before it became an industry, the servants of Námo escorted you a certain distance into his forest and then let you find the rest of the way yourself. This was far from pleasant or ideal. They are not suitable companions for any of the Quendi, and their pantomimes of our behavior had the opposite of the intended effect, but they were quiet and liked things colorless and dim, and when every nerve in your body feels like it is waving exposed in the wind, even their creepiness became tolerable if it gave a little peace.

Aunt Eärwen has raised her hand to Artaher’s shoulder. She means to comfort him, but he is inclining away from it because it hurts, and she seems oblivious. Another carriage cuts in front of us. wa-HONK and Artaher flinches again, and she sets her hand more firmly upon him till he is nearly tipped over, and even with my mind pressed shut to his thoughts, his distress is coming off him in red waves the way an open, red-hot oven will shimmer the air in front of it. I look back out the window, but my stomach is turning, remembering the first night I was bidden to sleep in my new body, when I couldn’t figure out how to lay down upon a body that felt scalded, and even when I wept, the tears hurt my face.

“Don’t touch him!” I realize I have blurted out. “His skin is new. It hurts. Leave him be!”

Aunt Eärwen’s eyes go wide, and her hand jerks back, the fingers curling upon themselves like a questing creature suddenly startled by a predator.

I whip around to face Findaráto. “Have you prepared them with nothing? You remember what this is like! Who cares about your dumb campaign, this is your brother.” And I turn to Arafinwë. “And you should too. This is not the first son you’ve seen returned.”

“It wasn’t that bad for me,” says Findaráto in a voice infuriatingly free of defensiveness but brimming with wounded innocence.

“Of course it wasn’t,” I snip and go back to my window. wa-HONK. Another interloper is easing in front of us from a carriage park, waving listlessly at our driver’s horn. I lunge forward to the window that separates us from the driver and shout through the glass, “For fuck’s sake, stop honking!”

Arafinwë should be used to profanity; he’s my father’s half-brother after all. His lips are parted like he knows he should say something but can’t quite muster the words. He’s had a dozen uneventful, tranquil lunches with me where I barely say a word and “Caranthir the dark” is but a construct for him to perform his guilt upon. Until now, I was a character in history, and his ability to empathize with me wasn’t much different than bringing a controversial, countertextual reading of an antagonist to a meeting of a book club. It wasn’t much different than his stupid republic, enacted only because he had the authority to make it so; there was no uprising, no marshaling under torches, no risk, no rebellion. He is seeing me differently now.

“Pengolodh was right,” I quip as I return to my seat.

Now the carriage ride is quiet, and awkwardly so. My aunt and uncle, I sense, have had the realization akin to a person walking across a frozen pond and, halfway across, discovering the ice is thinner than they knew. Findaráto has a maddening expression that conveys equal parts disappointment and practiced nonjudgment. Only Artaher is looking at me.

I’ve never liked meeting people’s eyes. When I was younger, it made the torrent of emotions seem even stronger; now that I can close my mind to them, I find that looking at someone’s eyes still allows a trickle, an intimation of what I have shut out. I do not realize that Artaher is looking at me when I let my eyes pass over him, and the complexity of what I see in his eyes before I swiftly look down at my own knees is more than I can parse without opening my mind to him.

I have never seen much of my cousin. When we were young, he traveled in a pack with his brothers Angaráto and Aikanáro and my brothers Tyelkormo and Curufinwë. My brothers were not always kind to me but neither was I always kind to them, and our antagonism was the opportunistic kind typical of siblings close in age, part of a large family, and ever jockeying to be noticed. My brothers’ unkindness was but a thread in a larger weft where they’d tease me over something one of our cousins had siphoned from my thoughts in the afternoon and, by evening, would come to my room for consolation during one of our parents’ increasingly vicious fights. Angaráto and Aikanáro stood forth in my mind as the ringleaders; I felt them ever at the perimeter of my mind, like coyotes looking for a break in a fence; they had their choice of victims and consistently chose me. And Artaher—he was there. I remember him there. But in my memory, he stood at the back, his face partially obscured by hair he tended to wear unbound. He prowled against my mind too, but he never had to search for an opening; he simply took it.

I batten down my mind as Námo instructed me. I tuck away the tendrils of my thoughts and draw in my emotions, almost like an inhalation, breathing in scent and smoke, and then I close my mind upon it. It is a feeling like gritting your teeth. Thus armed, I raise my eyes to his and stare back until he is the one to look away.

Confetti

Read Confetti

Artanis and her husband apparently sailed back at the start of the Fourth Age to Tol Eressëa and didn’t waste much time before setting up the island’s largest and most renowned all-inclusive resort. I don’t know much beyond that because—typical of Doriathrim behind their magical fence, squatting in opulence with their own kind while everyone without grows their callouses—they haven’t been exactly forthcoming with invitations to those of us outside their immediate family. Not that I’d want to go anyway; I get the occasional brochure among my junk mail, and the place looks entirely too … chummy, like you can’t sit on the beach with a whiskey without at least a dozen people trying to put oil on your back or holding your hand till you frolic in the surf or lobbing a frisbee over your head. I like the water quite a bit—I swam in the Helevorn every day it was free of ice—and might like to go, but not if I’m going to be forced to lay facedown and naked with just a towel across my butt while a Telerin masseuse lines my back with hot rocks.

I have happily commenced my plan of not doing anything to “mentor” Artaher. I’m back to work at the information kiosk in the Tirion Public Building that used to be Arafinwë’s palace before he unkinged himself. It’s a new fiscal year, so it’s a particularly busy time as new documents replace the old, and instead of sitting on my rotating chair and watching for people to come in through the front door while hoping not to be startled—visibly at least—by someone walking up from behind me, I am replacing old pages in my reference ledgers with new. Some lesser inventor from the Noldor who remained behind made a device that, with a couple workings of a foot pedal, minces paper into tiny squares where it can be repurposed as confetti; thus, Arafinwë’s government is funded at least in part by the festival industry that buys confetti from us by the bag. My union has negotiated an hour of paid leave for every bag of confetti that I produce, so I’ve been quite contentedly chopping up old papers all day. At night, I go home and fix crackers and soup for supper and play my lightning-guitar or tinker with a palantír that is disk-shaped and small enough to fit in your pocket. Right now, it is distorting people’s faces in comical but wholly unacceptable ways, but it will send messages. Sometimes, Amarië and I play in one of the more squalid clubs on the shadowy side of the city, me on the guitar and her screaming her poetry over the heads of the crashing crowd. I receive a chipper “Appointment Reminder!” card each week about therapy; I put it into the confetti maker to lend the next bag a little color.

And then I get one of those dull, white, soulless envelopes in the mail. It’s been almost two weeks since I left Artaher with his parents, and I expect I’m about to be chastised for failing to forsake my evenings to make sure he’s grasping democratic principles and to help him fill out job applications and to forewarn him that when he’s summoned to a healer to check that his new body is functioning as it should, he will be poked in some very weird places.

Instead, there is a colorful flier for Artanis’s resort, folded so that it fits in the envelope, and a ticket for a passage by ship to Tol Eressëa, departing in two days.

The next day, I put the flier into the confetti machine without having opened it, where it becomes tiny festive squares decorated with smiles and frisbees and naked, pedicured feet. I have no intention of going and am working earnestly on turning the orange-tabbed section of the blue ledger into my third bag for the day when my supervisor comes over to take my place so that I can “write directions for my coverage for the next week.”

My foot quickens on the pedal, seemingly against my will. “Coverage? I don’t have any leave left.” Amarië is always after me to use my full union benefits, and I don’t argue. It’s not like I like it here—I didn’t exactly like making hoes and grill plates in my father’s forge either—but it has become surprisingly comfortable in the way that my father’s forge, with its leaping flames and caustic chemicals, was once comfortable as well. Still, I’d rather be home.

“This came from way on high,” my supervisor tells me, and when I don’t look impressed, elaborates, “Lord Námo high. You’re to be given a week off, paid and covered. And before you argue about the confetti,” he quickly adds, “you’ve been averaging two bags a day, so you’ll earn two hours leave each day as well.”

I gesture at the bag by my feet. “This is my third bag, and it’s almost full.”

“Three bags, then.”

And that’s when I realize the order is indeed from on high on high. One difference I’ve noted between Tirion of old and democratic Tirion of today is that everything seems suddenly more valuable. We used to be lavished with whatever we desired: the best of food and wines, luxuriant clothing and resplendent jewels, every whim and fancy actualized with just a word. Now, nothing is lavished; it is parted with, the same despondent language that one used to use when taking leave from a loved one. Amarië would tell me that what was once lavished in fact came from the majority of people who lived in the lower streets and whose lives haven’t changed much (or have changed for the better), and today’s frugality is a symptom of equality. Regardless, every iota matters now as it never did before. If they are willing to part with three hours of leave a day, this is serious.

I still don’t plan on going. I’ve walked home, turning over an idea for my pocket palantír in my mind and looking forward to an uninterrupted week to work on it, when I realize that the little shack I built for myself behind my mother’s house has a rental cart tied in front of it, and the horse—a sturdy palomino—is cropping the grass I never both to clip.

Nelyo is in my shack, holding up one of my shirts by either shoulder and grimacing, while my mother assembles a neat stack of trousers in a travel trunk. He doesn’t greet me when I enter but announces, “Carnistir, this is hideous.”

I grab it from his hands. It has armpit stains and a streak of oil down the front. “That’s a work shirt!”

“I should hope not,” he replies.

“Not the Public Building!” I jab my finger toward the second room in my cottage where I keep a workshop. “That! That work!”

“Thank goodness.”

“Why the hell are you here, going through my clothes?”

My mother ignores my outburst at my brother. “Little love, do you have anything suitable for the coast?” I always wish I could be irritated with her persistence in calling me “little love,” which she’s done since I was actually little. I’m thousands of years old, with two daughters, once a lord of my own lands, and in my second body—yet it unmans me every time. “Not really,” I say, deflated. “I’m not planning on going to the coast,” even as I know I’m going to the fucking coast.

Nelyo eyes me up and then says to our mother, “Findekáno is close to his size and has too many clothes. I’ll pack some extras of his.”

“I’m not wearing Findekáno’s clothes!”

Two days later, I am standing on a dock on Tol Eressëa wearing Findekáno’s T-shirt—red with a crowing rooster that says LORD OF BIRDS—being hugged by Artanis for the first time since we were kids, with my family milling behind me and Artaher at my side.

Plunge

Read Plunge

My cousin is still wearing Nenya, and I can’t help but wonder if some dregs of whatever power Tyelperinquar put into the ring is still at work because the Glittering Sands Resort and Spa has an ubiquitous shine of artificiality that belies being constantly battered by wind-driven sand and saltwater. The ring glitters on her hand as she gestures at a pair of palm trees bending to perfectly frame the sea for patrons of the juice bar and then beyond to where a pleasing arc of reef makes the emerald-blue sea calm enough, in her words, “for children to frolic and bathe while their parents nap in one of our fully serviced open-air villas.” We are being given a grand tour slick with the same marketing lingo from her brochures. Every now and then, her husband pipes up and restates something she said in less lustrous terms.

“The sea is really calm there,” he says. “Because of the reef. Which also has a lot of pretty fish.”

“I have scheduled you an outing on the reef,” says Artanis, “with our best snorkeling guide.” Her voice has always been low, almost manlike, but like all of Arafinwë’s children, seems to always brim near to laughter.

All of Arafinwë’s children except Artaher. Artaher is like the riddle where you’re told not to think of elephants, and so naturally, all you can think about is elephants. I was—am—determined not to render him the assistance to which I’ve been assigned, and so naturally, all I notice is him. His hair is completely unbound, falling arrow-straight to the middle of his back. The Arafinwions except Aikanáro always had fair, almost flyaway hair, and the breeze off the sea keeps blowing it into his mouth. He’s always tucking it behind his ears. His cream-colored tunic is old-fashioned and looks out of place over cargo shorts, but someone had the good sense to give him a shark-tooth necklace and a pair of sandals, which makes him look remarkably like the Teleri who work the docks and peddle drinks on the beach. He says almost nothing. Actually, he says nothing; he says even less than me. (Because I have said one thing. When we were getting off the boat and the smell of the day’s catch hit us, Findekáno—behind me on the gangplank—said, “Whew! Carnistir farted!” and I retorted, “You farted!” but that’s been the extent of what I’ve said today. Artaher manages to be more taciturn than even that.)

Artanis leads us down to the beach, where a row of lounge chairs illustrates to me the full absurdity of all of us being present here. If I’d brought my pocket palantír, I could have tested it to communicate with the person at the other end of the row of chairs from me. We take up half the beach, just our ridiculous family. Even Findaráto has taken a few days off from campaigning. The Noldorin Congress is in recess and the schools are on summer holiday, so the next most inaccessible relatives—Anairë and Nelyo—are here as well. Only Amarië didn’t come. When I asked, she shrugged and reminded me that, since she doesn’t believe in marriage anymore, even though she lives with Findaráto and “enthusiastically shares his bed” (her words—I’m long over her but would still rather not know about it), she’s technically not family, nor is she fully certain that the Tol Eressëan workers at my cousin’s resort aren’t being exploited to provide Noldorin landlubbers with a “fantastical escape divorced from the rigors inherent in our new democratic system.” She’s my best—my only—friend, and I wanted her there for my sake, but our friendship has no allowance for sentimentality and I didn’t know how to say this and maintain my dignity, so I growled, “Fuck that shit,” and she got excited and read a draft of a poem about the evils of escapism to me, and then I went home to a trunk full of Findekáno’s shirts and left the next day.

I grab the chair on the end and immediately slide it away from everyone else. Artaher goes to the other end, but when Eärwen realizes where I’ve settled, she offers the chair next to me: “Honey, why don’t you take this one next to your cousin?” Nelyo and Findekáno end up separated, which my brother doesn’t seem to mind but Findekáno protests, so there is another reshuffling, and once everyone’s settled, we’re one chair short, and Artanis’s husband is left standing. “Oh, I completely forgot to have one set up for you!” Artanis says, and it’s a few minutes before one of the beachboys drags one down the sand for him. “Well I was supposed to take that group out to the reef but they never showed up,” he offers by way of apology for her mistake. She’s explaining to Anairë about how they refine saltwater to do the laundry in, to sustain the limited water resources on the island.

A beaming server begins bringing cocktails. “Oh, I think you’re mistaken, we didn’t—” my mother begins, but the woman cuts her off with the plunk of a glass and, “I know everyone’s favorites. Trust me,” and a wink.

“Trust her!” Artanis agrees with a deep chortle.

The server brings me a whiskey neat. I sip it: It’s from the distillery on a frigid, damp island off the coast of Araman. I decide to trust her.

Next to me, Artaher ends up with a glass of miruvórë so golden that it might be distilled sunlight. Findekáno has already taken off his shirt and has been given something bright blue and in a big bowl, which he has halfway finished. Two more gulps and he’s done, whooping down to the sea and, once waist-deep, diving in. Findaráto hesitates for only a moment before jogging down to join him. Anairë and Eärwen go arm-in-arm, deep in conversation. Arafinwë waits for my mother and Nelyo to slather each other’s backs with sunblock before the three of them walk down together. Artanis shouts at a beachboy who’s setting up an umbrella wrong and takes off down the beach, leaving her husband to stare after her with uncertainty plain on his face as to whether he should follow her or join her family. He finally walks down to stand at the water’s edge.

I sip my whiskey. “You should get in. The water looks delectable.” I borrowed that word from Artanis on the grand tour; she’d used it to describe the complimentary breakfast.

Artaher turns to face me. He has not undressed or even removed his sandals. His golden hair fans against the dark green cushion of the chair. There is something in that motion—in the turning from one’s back to curl on one’s side—that feels uncomfortably intimate. His new skin is pale and unmarked by so much as a blemish. “You’re the swimmer. Not me.”

I have schooled myself out of humiliation, or so I thought. I used to wear my embarrassment as plainly as, apparently, I broadcast my emotions, going red in the face and my tongue—already a useless slug much of the time—feeling as though it had swelled to fill my mouth. Námo schooled me out of that too—but don’t feel soft emotions for him. He did so by humiliating me, frequently and thoroughly, to where shame became as a limb overused past the point of exhaustion, until it’s gone senseless and limp. Or I thought he had. But when Artaher mentioned swimming, I felt the familiar sensation of my stomach bottoming out, the way I remember feeling when jumping off cliffs with my father and brothers. The flush started in my chest, over my sternum, and heated my neck like a tree catching fire. He couldn’t have known I was a swimmer. I swam in Helevorn, long after he’d exited my life for his own small realm on the other side of Beleriand. No one knew that I swam in the lake except my daughters and Taryindë, because I dove off the rocks outside my house and no one dwelled in my house—no servants, no councilors—just my family. My eldest daughter would watch me sometimes from the rocky beach; she was apt to worry.

This remark about the swimming, it was like a pinprick after a sword gash, but this is how it began, back then, with the little observations that no one could have known but me. “Carnistir, I’m sorry you were released by your calligraphy tutor, that’s a shame.” Angaráto: one night when our parents were drinking wine and discussing court politics in Arafinwë’s sitting room, and we middle cousins had nabbed a bottle of cooking sherry from the kitchen and were passing it around under one of Arafinwë’s topiary abortions. And Tyelkormo, wide-eyed and guileless, “You were released from calligraphy? What did you do? Does Atar know?”

No one knew because I hadn’t told anyone.

I realize I’ve also flopped over on my side to face him. “Stop this shit now,” I hiss. “Not again.”

His eyes were two wide panes of blue in his face, his confusion and unease plain even with my mind clamped shut. “Carnistir, I—”

“No. You think I don’t remember? What you and your brothers used to do? Listen in on my thoughts and then weave them into conversation with others like I’d trusted you with my confidences? I knew no better, and you took my pathetic ignorance and made it into your joke.”

“Carnistir, I—”

“Don’t even start, you little mottled mushroom fucker.”

My brothers used to enjoy my insults; they would rile me up just to bring them on, and their laughter—bright with their love, their love for me, no matter how strange and sour and worthless I was in every other way—would bathe me cool and clean like the waters of Helevorn many years later, when our laughter came less easily.

Artaher’s reaction was different. The bridge of his nose flamed pink, and his glass-bright eyes narrowed with anger.

“Listen! Stop interrupting me!”

His own voice had been reduced to a hiss. Beyond us, our family played in the sea.

“I know perfectly well what happened! But I meant nothing by it. Taryindë told me, in Mandos.”

I used to read my messages each morning in my study overlooking the lake. The terror, the hate, the bloodshed, the malice—from Morgoth and from us. Plans from my brother for a war machine; a debate over how long it takes to starve a company of Orcs; the chemical construction of poisons. Images assailed me from Valinor: leaping from a cliff, my stomach bottoming out, with Tyelko whooping behind me. My father scolding me in the forge and Curufinwë squeezing my hand under the worktable. Losing my virginity to Taryindë in my childhood bed and later sobbing my terror to Nelyo that she might have fallen pregnant. Macalaurë making rude limericks about me and me throwing a handful of peas at him right as our mother came in, and I got in trouble and he didn’t. The twins, tiny and still damp from birth, being placed in my arms, and my father saying, “Relax, they won’t break.” In my study overlooking the lake, I crumpled the messages in my fist like, by crushing them, I could break apart the shells that spoke and looked like my brothers and free what was lost but surely still there? Every day, I left those messages on my desk for Taryindë to use to start the fire in our bedroom later that night. The door to my study opened directly onto the path that led down to the rocks. I would discard my boots under my desk, but the rest of my clothes came off as I strode to the rocks’ end. The lake plummeted away there, its bottom out of reach of all save, perhaps, the Telerin pearl divers, but we’d left them slain on their shores. Naked, I dove in. The water closed, dark and cold, upon me with the force of a blow: Tyelkormo’s fist to my temple when I shouted, “We cannot go to save him!”

You’re the swimmer. Not me.

This water, when it closes upon me, is as warm as my bath and flat as a mirror, thanks to Artanis’s fucking reef. I plunge into it, and that old motion is still there, as though I’ve never changed bodies, of pulling myself through the water. There is a slight current, but I fight it out past the reef, where the waves begin to break over me so that I choke and sputter with most breaths. I pull and pull until my arms ache, and my family is small on the shore behind me.

Zurb Zurb Zurb

Read Zurb Zurb Zurb

My arms are trembling when I pull myself up on the dock. I collapse into a wet heap for several long moments, enjoying the solidity of land beneath me, until I realize that my head still thinks I’m in the water and is reeling with the motion of the waves. It is twilight, a cornflower sky stained pink in the west, where I know Námo’s servants are enacting a discordant farewell song to Arien and listlessly capering out their delight at the coming dark. Eärendil is drawing nigh to the moon, almost full, in the east. The light of both cast a shimmering road upon the sea.

My, aren’t I poetic tonight.

Artanis informed us earlier that we had dinner reservations at the finest of the several restaurants on the resort. I can hear music—not the jolly, percussive sounds of the Tol Eressëan Teleri but violins and harps—music made for Noldorin tourists—and the clink of crystal and silver, and the hush of voices. There is a muted golden glow of candlelight spilling from windows open to the sea. After my swim, I’m ravenous, but I’d sooner eat one of the fish just recently keeping me company than join my family in there. It’s just as well. She probably forgot to include her husband in the reservation; he can have my seat.

I haul myself to my feet. It’s been a long time and a different body since I swam so far, but I remember the staggering walk of my first steps ashore. My daughter used to meet me on the rocks and catch my arm so I wouldn’t fall back in, which did happen a few times. No one is here to see me now so I weave with—

I stop. I was mistaken. Someone is here.

Artaher. He’s pulled up a chair on the dock and is drinking another glass of miruvórë. Actually, judging by the fumes about him, he never stopped. I imagine the smiling beach server bringing him glass after glass after glass. “I know everyone’s favorites! Yours is to get blind drunk! Trust me!”

I stand in front of him, shirtless and dripping, my feet set apart to keep me from staggering. “What.”

“I wanted to apologize about earlier. I know what my brothers and I did to you when we were younger—”

“And what you perpetuate with your little sycophant Pengolodh, who thinks I chose to hate you with the same lack of consideration I’d use to choose a hat.” I want to stay angry with him; I want to rouse him into an argument.

“Pengolodh was Turukáno’s sycophant.”

“And your brother’s by extension.”

“Yes, but Findaráto had nothing to do with this, and his good graces didn’t extend to me. Pengolodh wasn’t exactly kind to me either, from what I hear.”

“Well, you did have the most successfully concealed kingdom after Gondolin and choose to announce it by building a fucking bridge to your front door.”

He breathes deep. His eyes flutter closed. I recognize the gesture from therapy: He is counting to ten. I tap my toe along. When he reaches ten, he says, “The bridge was—not now. That’s not what I came here to say. I came to say—what we did to you—that was all Angaráto and Aikanáro. And your brothers. And … me. I accept my role in it.”

“Don’t bring my brothers into it. They laughed at your jokes but if they’d known what you were doing—”

“Well, I’m sorry for what was done then, more than you’d know, and it certainly wasn’t my intention to make you think I was doing it again now.”

“Why were you talking to my wife?”

“In Mandos?” He laughs. Drunk and less inhibited, he sounds a lot like Findaráto without inspiring the sense that one should be tiptoeing around him while simultaneously groveling and finding oneself wanting. “Because she cornered me one day and unleashed the full force of her wrath upon me, for how I treated you. For the damage I caused to our people and then allowed the Doom of Mandos to be blamed instead of taking responsibility. I see why she rode into battle with you. I wouldn’t want to meet her with a sword.”

Taryindë. She would do something like that, yes. Briefly, her image flits across my thoughts, in her dark violet cloak, feet wide apart, a bright sword in her hand, standing over the dark heap that was me. It’s no memory—I was unconscious after a fall from my slain horse—but how I know, somehow, it must have been. The lacuna between that moment and when I woke, groggy and sore, and knew she was gone, I allow to stand, unexamined. She was the only one who knew, fully anyway, about what happened with my cousins. Nelyo knew bits and pieces, and all of my brothers would have remembered my humiliation but would have had no idea how Arafinwë’s sons discovered I was in love with Amarië to set me up to propose to her. After my confrontation with Angaráto about Doriath, I started to tell Nelyo, but frustrated by me already, he cut me off. “Do you realize how foolish it sounds, Carnistir, to claim you’re disrupting the peace between Eldarin nations because you’re still sore over a childhood prank? You need to move on,” and I never came close to confessing it again.

“I’m sorry I’m not her.” I start at Artaher’s voice, barely audible and hesitant. “I know—I know you came to the Halls, thinking she was being released. I can’t imagine your disappointment to find me instead.” He tips back the last of his miruvórë and tosses the glass into the sea. It sparkles once, twice before it becomes just another glitter of moonlight on the waves. He reaches beneath his chair. “Here. I brought this for you.” It is a bottle of the whiskey from Araman.

“You steal booze now?”

“I’ve always stolen booze. It was my contribution to the—” He stops. He was about to bring them up again: his brothers and mine, the five of them inseparable and somehow, even though I was right in their midst, they never considered me. “My father used to think it was Aikanáro.”

I uncork the bottle and take a drink straight from it.

He rises and sways on his feet without the excuse of having swam in the sea for the past several hours. “Won’t you sit?”

“Don’t be stupid,” I tell him. “I’ll feel ridiculous with you sitting at my feet like you’re my grandson listening to me creak on and on about the Years of the Trees, and I don’t want you standing and looming over me either. It’s creepy.” We both end up sitting on the edge of the dock with our feet dangling toward the water. I couple tips of the bottle, and it matters far less that it’s Artaher I pass it to. He’s more of a stoic about it than I expected; he doesn’t even wince when he swigs it. “I didn’t think it was Taryindë,” I say. “I’m supposed to be your mentor. That’s why they sent me.”

“Mentor?”

“Don’t ask me. We’re supposed to be ‘aligned.’ That’s what my therapist says. I think it’s probably a creative continuation of Námo’s punishment—excuse me, rehabilitation—of us both because I can’t think of a single thing you and I have in common.”

The bottle comes back to me. I hold it up to the moon and watch the light quaver in its depths like a silver coin. I salute the Silmaril and drink long.

“I think we have a lot in common.”

I wipe my mouth on the back of my hand. “Bullshit.”

On an empty stomach within an exhausted body, intoxication is swift. Artaher is—confiding in me?—it seems? I hear his voice going zurb zurb zurb off to my right, but what he’s saying doesn’t make any sense. Sickness. He speaks of sickness, a word I learned from Haleth when her healers brought out people on litters from behind the stockade. The sick, she said. I could never read the thoughts of Mortals, not like I could Elves—else the treachery of Ulfang would never have happened—but I sensed a miasma, a distortion about them. I learned from her about this sickness that would take her people from time to time. They all fell to it from time to time, some worse than others. Some—many—most?—died from it.

I shove the bottle into his chest and force myself to focus. He interrupts himself to gulp from it and shoves it back at me. “—I’d be sick with it, with the future, paralyzed by what I saw. It was like being told to cross a meadow, and you know there is one trap in the meadow, but it is hidden in the grass. You will never find it. And every step you take, you worry if that is the single small action that will touch off the mechanism and set the thing into motion that will snap your leg in two. Only imagine that the trap sentences someone you love, or your whole family, or your whole people to an awful death. I couldn’t get out of bed. That the fate of others should depend on someone as stupid and pitiful as—”

I let his voice fade back into zurb zurb zurb. My bones suddenly felt as soft as warm wax. I sag against him.

Briefly, the zurb zurb stops. An arm slips up my back and around my shoulder.

When I fell from my horse at the Nirnaeth, unconsciousness was not instantaneous. Darkness closed upon the edges of my vision; I tried to wave it away like one might banish a cloud of blackflies. My horse was screaming as it died. My hand stretched up against a bone-bright sky.

Unconsciousness presses at the edges of my vision now. I drink again and dare it to come nearer. The hand rubs my back; another takes the bottle from my hand as I raise it again. A new set of memories emerges. Touching. Being touched. I haven’t been touched since returning to this body. My mother and brother have hugged me, perfunctorily, like they fear they might hurt me. They used to cradle me with abandon. For a long while, I was the smallest one. And Tyelko would press against me on cold nights.

And Taryindë: a hayrick in autumn, the festival muffled in the village behind us, a flask of nabbed spirits passing between us. “Keep close,” spoken under a pretense of keeping her warm. Her arm around my back, under my tunic; my arms both around her, kissing, the flask dropped and forgotten; we’d kissed before, we’d practiced on each other, but this was different. Her hand on the inside of my thigh and my hand on the ties to her tunic—

“—no, you are drunk—”

Schoolboy

Read Schoolboy

I wake up the next morning in a bed that isn’t my own, with a dry mouth and a pounding headache. Spears of sunlight are jabbing through the window and into my eyes. A breeze pushes in the gossamer curtains and the sounds of seagulls screaming for rights to the guts and scales from yesterday’s catch.

My heart clenches in a panic—where am I? whose bed is this?—that just as quickly subsides. I’m at Artanis’s resort. That’s why I’m not bundled into my own windowless shack back home outside of Tirion. There’s a painting of a ship, sails plump with wind, on the wall and a conch shell on the table: standard fare for these kinds of places, I know, without ever having been to another such place but here. I roll away from the stabbing sunlight and press my pillow over my ears to shut out—or at least muffle—the sounds of the gulls.

It wouldn’t be the first time I awoke in a strange bed, though it’d be a first for this body, which is as virginal as new-fallen snow. As a young man, experimenting with Taryindë had awakened my body (and hers), and then she went off to the south for her apprenticeship, and we gave each other permission to sate our urges with others. “If we return to each other, we’ll know,” I remember her saying to me. Neither of us had yet pronounced the word love to the other. But in those long years, the Calarnómë—the labyrinthine streets of Tirion that lay in the shadow of Túna—became a place of refuge for me in a progression much like last night: exhaustion, alcohol, sex, and awakening to wonder what my lover would look like when I rolled over.

I remember being told that the urge would diminish as I aged, but it never did for Taryindë and me, even once we knew our second daughter would be our last child. We used to laugh at our own insatiability and took it as a sign of the same vein of perversion that drove us into exile in the first place. But I have no interest in sex now. My lack of desire is a relief; to romp about as I’d once done feels exhausting now. I am pleased, then, that the unfamiliar and nondescript bedroom in which I have just awakened is solely due to my cousin’s dull, kitschy taste in decorating for tourists and not because the obliteration brought on by last night’s drinking led me to a questionable choice, considering my family are in the rooms around me, and a return to bodily needs and a separation from Taryindë far more durable than an apprenticeship.

I roll over, away from the light, and my nose bumps someone’s shoulder and there is blowsy golden hair, blue eyes, skin already browning—without burning, without freckling—from just a day’s exposure to the sun.

The next half-hour is illustrative, and I perform the full range of emotions for which I am renowned.

He brought me up last night because (he alleges) I could not walk on my own. Lacking the key to my room and not wishing to reveal my inebriation to my family, he put me to bed on the sofa in the closet that Artanis claims is a sitting room.

I did not stay there long before entering the bedroom and getting into bed with him.

I kissed him, on the dock and in the bed. He did not initiate, though he reciprocated.

(“I did not know you liked boys too. It was always the girls who talked about you in the Calarnómë.” He sounded like a fucking schoolboy. I told him as much.)

He had touched my thigh and chest. No more! He swore to it. (“I wanted to. But you were drunk—I didn’t. I swear to it.”) I touched him thoroughly. That’s how he put it, and I didn’t ask him to elaborate. I bit him where his shoulder met his neck. He showed me the mark.

“I think you could have made different choices,” I say when he is finished, and even though it is my voice, it might be my therapist, or Uncle Arafinwë, or Lord Námo. I laugh. I expect him to, but he doesn’t ask me why.

At last he says, “I didn’t want to.”

No Interest in Fish

Read No Interest in Fish

I suppose I am guilty of assuming my cousin was sexless. Sure, he has a daughter—Finduilas—so he must have copulated with his Sindarin wife at least once, but if you’d asked me, I would have estimated it had been only once.

Angaráto and Aikanáro performed their sexuality, at least when they were with us cousins, in their vocal lusts for certain women and boastful prattle, always trying to one-up each other and my brothers Tyelko and Curufinwë, but Artaher never made boasts or claims or seemed even to notice women beyond what was required to laugh at his brothers’ jokes. He was always modest, even a little pious, his clothing a season behind or just slightly awkwardly fitted like he didn’t care to be noticed much less admired.

I suppose at least drunken me notices him, though. During the complimentary breakfast buffet, Arafinwë makes excuses for Artaher and his “illness” (that word again! no one bothers to make or require excuses from me) that kept him from dinner with the family the night before. I have to excuse myself because the thought of correcting Arafinwë—no, Uncle, you are wrong; your son was gone because he was drinking whiskey and engaging in heavy petting with me on your daughter’s boat dock—in front of everyone makes me feel like all the blood in the upper half of my body has plunked down into my cock and balls, so I flee to the water closet.

Artanis has a schedule of activities at each of our places, printed on pale blue linen cardstock. BREAKFAST in the TIDEPOOL BUFFET is followed by SNORKELING (via the SPRING TIDE) out on her blasted reef. Artanis is long-limbed and golden in a pair of white shorts and one of the bikini-style bathing costumes debuted by the Teleri that have caused such consternation among the Noldor and the Vanyar. She leads us through an introduction to the fish we will observe on the reef, each illustrated by a brightly painted card. My mother comes to me with the sunblock. “You burned, all on your shoulders yesterday,” she whispers and makes me take my shirt off so that she can smear sunblock all over my shoulders and back. I cross my arms over my chest and refuse to look in Artaher’s direction, sneaking looks at my shoulders instead. She is right. My freckles have surfaced on my shoulders and upper arms; even the stupid sunburn couldn’t be regular, giving me hope it might smooth to coffee-and-cream worthy of any Arafinwion, but instead is splotched. I have no doubt that it will settle looking something like a piebald horse.

We are loading the boat, Artanis offering a helpful hand to each of her landlubber relatives as we step from dock to boat. The boat, called the Spring Tide, looks awful small for all of us. Her husband is driving; he is shirtless and as white as me, minus the freckles and sunburn. We all scramble for seats on the tiny boat with all the grace of crabs in the pot; I manage to finagle Findekáno between Artaher and me; he smells of the mimosa bar in the Tidepool Buffet and will be unnecessarily loud but—

“Artaher!” Case in point, he is already shouting at our cousin, who is right next to him. “Switch with me so I can switch with your father and get next to Nelyo!”

Which is how I end up on a lurching boat with my thigh pressed against Artaher’s. It is hard to decide which of us is more studiously avoiding the gaze of the other. His time in the sun yesterday didn’t leave him speckled and splotched, and he is tan as a Teler, which makes the blue in his eyes—what the fuck am I even saying? Practical Noldor all, we’ve tied back our hair to keep it out of the wind, except for him. The wind lifts it away from his face and neck and—

Artanis is struggling to find a place to store a stack of towels. “I’ll take them!” and I hold them in my lap, and she raises an eyebrow at me in genuine surprise and says, “Why, how kind of you, Carnistir!”

Artanis is explaining about personal flotation devices—only Arafinwë puts one on—and how to use the equipment. The boat hits a swell and lists, and Artaher grabs my knee to keep his balance. “Sorry!” he hisses and yanks his hand back.

—touched the inside of your thigh and then I realized you were—

I clutch my towels and press my knees together.