Illuminations by Dawn Felagund

Fanwork Notes

For my B2MeM project this year, I am doing small scenes and character studies of Pengolodh, one of the imaginary loremasters in Tolkien's story and, quite likely, the primary contributor to The Silmarillion. Pengolodh has always fascinated me as a character: one who feels omnipresent in the books yet about whom we know very little. In 2007, I authored Stars of the Lesser for Pandemonium and wrote Pengolodh for the first time. He's been quietly begging me for more attention since, so I am using this year's B2MeM as an opportunity to learn more about his character.

Fanwork Information

|

Summary: For Back to Middle-earth Month 2009: scenes from the life of young Pengolodh, the loremaster of Gondolin whose writings brought us The Silmarillion. Updated: Major Characters: Celebrimbor, Original Character(s), Pengolodh Major Relationships: Genre: Experimental, General, Poetry Challenges: B2MeM 2009 Rating: Teens Warnings: |

|

| Chapters: 9 | Word Count: 8, 971 |

| Posted on 2 March 2009 | Updated on 28 March 2009 |

|

This fanwork is a work in progress. | |

Learning to Make a Fire

Read Learning to Make a Fire

The manuscripts arrived in the thin light of morning. An errand-boy in the scriptorium, Pengolodh was scurrying across the courtyard, from the kitchen to the room where the scribes worked with their desks crowded against the east-most windows, preparing their pallets and waiting to leech every moment of light from the day. It was a cold morning, and three steaming mugs were balanced, shifting constantly to keep from burning any one spot for too long, in his steepled fingers.

Pengolodh's father was among the three loremasters huddled in a corner of the courtyard. A few fat flakes of snow swirled slowly to the earth; some caught in his coarse black hair.

The loremasters were unrolling a scroll, even here, in the semi-dark, even in the falling snow. Pengolodh's steps faltered at this. The vellum sheet was enormous. Even from here, he could see that it was richly painted. A snowflake caught on his eyelashes. One such flake upon the page would ruin and run the delicate painting.

His father turned then. The stern turn of his mouth made chastisement unnecessary, and Pengolodh hurried back into the scriptorium, the cups forgotten and scalding the pads of his fingers.

~oOo~

Later, the scribes and loremasters left for the dining hall to break their fast, leaving in a glut of gray robes and murmuring voices. Pengolodh and the other servants would eat after they had finished, picking from the bread and fruit that they left behind. Someone turned the hourglass with a dull tunk. They had till the sand expired to clean the scriptorium for the morning's work, to set three fresh sheets of vellum on each scribe's desk, to collect and fill orders for supplies, to move books from the librarian's basket to the desk of the loremaster who had requested them. It was a breathless hour.

In the librarian's basket today was a single small black book wrapped in a band of paper. "Sailaheru," said the paper in the librarian's tidy black-letter hand. Sailaheru was Pengolodh's father, and Pengolodh swept up the book and, with a trepid glance at the almost-expired hourglass, took the stairs two at a time to the topmost floor where the loremasters worked.

His father's study faced the east. Sailaheru had a saying about the correlation between witnessing the sunrise and cultivating wisdom and, likewise, a saying about loremasters who worked in the night. The latter was not a favorable pronouncement and was laden with the sort of vitriol usually reserved for answering a personal insult. As Pengolodh burst, breathless, into his father's study, the sun was just brimming on the horizon. He watched as light cascaded across the darkened sea, from horizon to shore. Pengolodh gently laid the book in his father's basket and paused. The scrolls Sailaheru had been studying in the courtyard were scattered with uncharacteristic untidiness across his father's desk.

Pengolodh tilted his head. He heard nothing from downstairs; the breakfast must have gone longer this day. Carefully, he unfurled one of the scrolls, holding it flat with the barest touch of his fingers at the top and bottom margins, fearful of leaving even a tiny trace of his betrayal.

The hand was unfamiliar, rhythmic and chaotic, like the waves in the sea. No loremaster of Nevrast--no loremaster of Nolofinwë much less Turukáno--had made this page. The illuminations in the margins were not the usual flowering vines and capering butterflies but a column of flame that knotted and twisted upon itself: Fire tamed, Pendolodh thought, and wrought into the logic of knotwork. There was no initial capital, just a slosh of black letters and the flames.

Pendolodh looked closer until his nose almost pressed the vellum. The scent of old ink lingered; ink from Aman, he realized. The flames were cadmium crimson brushed lightly, masterfully with shell gold. Even without the touch of light, Pengolodh could see the skill in the hand that had applied the gold. Mentally, he took it apart so that he might someday (or in secret, with a dried shell of his father's cadmium crimson and a thimbleful of discarded scraps of gold) tame fire upon the page, as this scribe had done.

The first fingers of light grasped the sill then and pulled the sun fully into the window. Light gushed across the page and Pengolodh leaped back. With a rustle, the scroll furled itself again. For a moment, with the gold flared to life in the light, he had feared burning his fingers upon the page.

On the Rocks

Write a story, poem or create an artwork where the characters face a great danger

or

where characters reflect on their reaction to a great danger.

Read On the Rocks

The third day of the week was his day off from the scriptorium, and Pengolodh always spent that day looking for the long flight feathers from gulls that made such suitable quills. Even when the sky poured rain; even on the one occasion when the snow piled to his knees (and feathers would have been impossible to find anyway), he went. He ached to hear the sound of the sea, loud enough to drown all but his most insistent thoughts; repetitious enough that his ponderings skittered lightly on the surface of the sound, never plummeting into the deeper and more painful introspections to which he was lately prone.

This day, the fog clung to the edge of the water and the sun rose behind it like a tarnished medallion. Away from the beach, Pengolodh knew, it would be unbearably hot. Was it not the third day of the week, he'd be struggling not to fidget in the scriptorium; sweat would be streaking down his back and pooling in the waistband of his trousers, itching there, but he would not fidget.

Pengolodh walked to where the rocks curved out to sea and, there, formed a cove where the young Sindar launched their bark boats in the relative calm. Something white lay upon the black, sea-slicked rocks, halfway out, and easily he made himself believe it to be a gull feather so that he had the excuse to climb out onto the rocks after it.

Pengolodh liked climbing on the rocks. He was terrified of it. Everywhere he saw surfaces angled to upset his balance, crevices waiting to snatch and snap his ankle, slick spots that would send him face-first into the rocks, catching himself and abrading his palms. His blood roared in his veins as he carefully picked his way across the rocks. He held his body so tight, so afraid, that when his feet touched the sand again, his shoulders ached like they did after a day bent over a desk. He quivered. He felt alive.

The white bit on the rocks was a discarded piece of shell, likely dropped and broken by a hungry gull, not even intact enough to make a child's pallet of it. Pengolodh moved past it. His careful gaze appraised danger at every point. He leaped, and expected to fall. Teetered. Outstretched arms held his balance. He felt his feet hug the rocks through thin-soled shoes. His feet would be bruised and sore; they always were upon settling to bed at the end of the third day. He breathed fast and deep through his open mouth. In this way, he made his way to the farthest rock and, there, settled to watch Nevrast.

From afar, he liked Nevrast. It might have been a pile of beautifully shaped rocks, something dumped there by the Valar when the light still came from the Lamps and they lived in peace on Almaren. Even his keen eyes couldn't catch the movement of individual Noldor along its streets and walls. His imagination filled the empty windows and doorways with people very much unlike the people who lived there.

But, today, a sound down the beach disturbed him: a shout, then another, then another. There was a rhythm to it. Around the curve of the beach, a crowd of Elves suddenly manifested. They were running, running in neat lines, five abreast and Pengolodh did not know how many deep. Each held something in his right hand in a way that reminded Pengolodh of the way one would carry a torch, keenly aware of the fire at its tip and the danger it would wreak if permitted to tip or topple. But, as the running Elves drew closer--the rhythmic shouts growing louder though no more comprehensible--Pengolodh saw that those were longbows in their hands.

But of course. He remembered now, four days ago, walking to the scriptorium with another apprentice and noticing the streets more crowded than usual with other young men like themselves. Like them, yet not. These young man slouched and languished and ran their fingers through their hair and talked to each other from the sides of their mouths if they talked at all. It was recruitment day for Nevrast's army, his companion told him as they walked. Those with no better opportunities would present themselves before the lieutenants of Lord Turukáno in hopes that they might be believed strong enough or fast enough or precise enough with sword or bow to be taken into service and, by that means, feed their families.

"We are lucky," his companion had said. "Lord Turukáno has already said that the scribes and loremasters will be last-called in event of war, and that the greatest among us will be shepherded away with the books so that the lore of our people never perishes from the world." We are lucky, he said, but his voice said, We are deserving.

The running Elves passed in front of the rocks, close enough that Pengolodh could see their faces. Some looked younger than he. They had wives and children already? He supposed that they did. Their bellies growled with no less insistence than his own, and this was not Aman: There were droughts and blights here, the fear of famine. Famine, that old Cuiviénen word, tricky upon his tongue. "We are lucky," he said aloud, though he did not know who we was any longer. "Lucky." He wondered what the running Elves imagined would lay around the next curve of the beach in the eventual war in which they had agreed to fight. He wondered if they thought to die of rot from a spear wound in the gut was better than to slowly perish of hunger. He wondered if they imagined at all.

Chapter End Notes

The personal reflection that inspired this vignette is on my website.

Snow Day

Create a story, poem, or artwork based on the circumstances, experiences, or feelings associated with that moment.

Read Snow Day

"--regretful."

Pengolodh drew himself from sleep with the same deliberate force as one dislodges his foot from a mud puddle while taking care not to lose his boot. It felt like someone had lodged an anvil between his ears. He doubted his ability to lift his head from the pillow. But he must--

His room was done in charcoals, for the Sun was just rising from her own slumbers in Vai. Downstairs, a door snicked shut; his father's friends shared Sailaheru's views about the virtues of rising early. Pengolodh heard the front gate squeak open, then shut. Any moment now, his mother would lightly roll her knuckles across his door. "Pengolodh," she would call gently. "It is time--"

The bedroom changed from charcoals to a gray wash. Pengolodh blinked. It was strange; too early for such prolific light. It should not be so light for a half-hour at least. And where was his mother? Wincing, he lifted his head from the pillow, careful that he should not dislodge the anvil and send it sliding into the backs of his eyes, and propped himself up on his elbows.

It was white outside, all white. He had seen snow before, of course, but never so deep that the Elves on the road had to lift their knees to comical heights to trudge through it. They looked like shorebirds, picking their ways among the wetlands, looking for crabs. They wore the same fussy, fastidious expressions. He would have dared a laugh but feared that it might unsettle the anvil.

Having accomplished lifting his head from the pillow, he decided he might as well use the momentum and swing his feet to the floor. It was best that his parents not suspect how late he'd been studying anyway, using one of the Valinorean lamps to read his books under the blankets. His mother came in once, with a candle, and he had to flop his body upon the lamp to hide the light, and he feared he'd broken the spine of the book in doing so as well. But that was the least of his concerns today.

Even with thick socks on his feet, the floorboards were achingly cold. The usual smell of breakfast cooking did not greet him and made the house feel colder. His father would be proud, he hoped, of his son presenting himself voluntarily on exam day without wringing more time with his books from the final minutes before he had to depart for the hall. Most--nearly all--did that. In truth, Pengolodh did not think his head could hold much more, not with that anvil balanced there between his ears. The kitchen was dark--he wondered where the cook had gone, or rather, why she had declined to show up at all (for surely she knew that this was his exam day)--so he proceeded into the front room, where the firelight made him wince, he hoped imperceptibly. His mother was grinding pigments with a small mortar and pestle, and his father was writing in one of his books, dipping his quill into a bottle of ink balanced on the arm of his chair. Neither, Pengolodh noticed, had yet laced on their shoes.

"It seems you are in luck," said Sailaheru, without looking up from or slowing in his writing. "A skylight broke in the hall from the weight of the snow, and your master has most generously decided that you should not sit upon a pile of snow to do your recitation. Your exam has been postponed until tomorrow."

Pengolodh had read the original works of Rúmil, had seen paintings done by the finest hands in Valinor, had even once--though his father did not know this--sneaked a look at flames wrought in crimson and gold by the adept hand of Fëanáro, but nothing, he thought, nothing compared in beauty to the sight of the Sun rising in the cozy square of his bedroom window, watched from within a warm wrapping of quilts.

Chapter End Notes

The personal story that inspired this piece can be found on my website.

Yes, there is significance to the term "Valinorean lamp." I doubt the people of Turgon were very eager to honor its inventor with the usual term "Fëanorian lamp"!

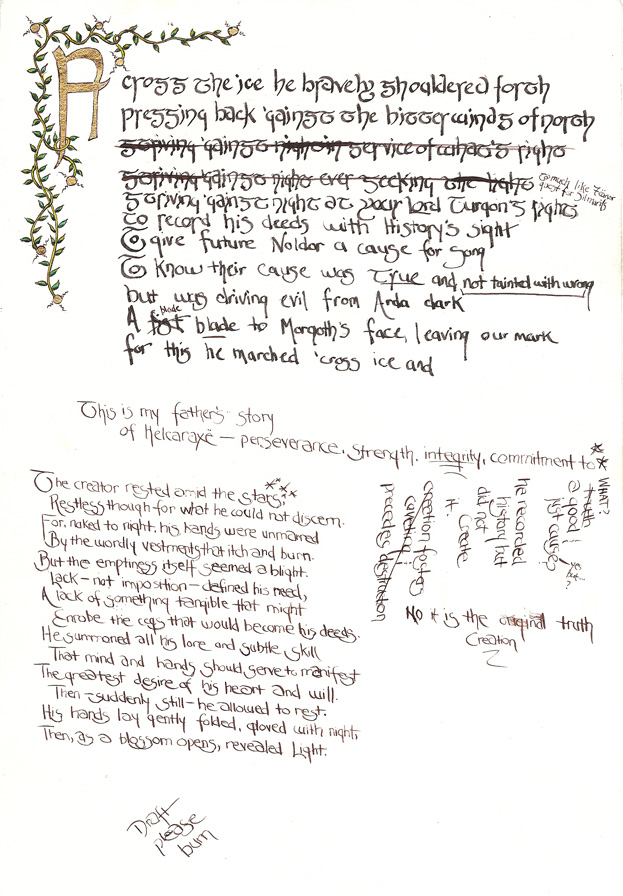

"A Poem for My Father" and "Creator"

Write a story, poem or create an artwork based on characters who are role models for their people.

This is a rather strange project: It is an illuminated page that Pengolodh started, messed up, and changed to something completely different. Visitors on dial-up should be aware that there is a rather large image.

Read "A Poem for My Father" and "Creator"

A Poem for My Father,

Authored by Pengolodh of Nevrast, YS 78

Across the ice, he bravely shouldered forth,

Pressing back 'gainst the bitter winds of north,

Striving 'gainst night in service of what's right

Striving 'gainst night, ever seeking the Light

Striving 'gainst night at his Lord Turgon's right,

To record his deeds with History's sight,

To give future Noldor a cause for song,

To know their cause was true, not twined with wrong

But was driving evil from Arda dark,

A fist blade to Morgoth's face, leaving our mark.

For this he marched 'cross ice and

Creator

The Creator rested amid the stars,

Restless, though for what he could not discern.

For, naked to night, his hands were unmarred

By the worldly vestments that itch and burn.

But the emptiness itself seemed a blight.

Lack--not imposition--defined his need,

A lack of something tangible that might

Enrobe the cogs that would become his deeds.

He summoned all his lore and subtle skill

That mind and hands should serve to manifest

The greatest desire of his heart and will,

Then--suddenly still--he allowed to rest.

His hands lay gently folded, gloved with night,

Then, as a blossom opens, revealed Light.

Chapter End Notes

Footnotes for the Curious:

The personal reflections that inspired this piece can be found on my website.

That Pengolodh wrote "A Poem for My Father" in YS 78 is based on three important dates from The Grey Annals:

- YS 53: Turgon discovers Gondolin

- YS 64: Work begins on Gondolin

- YS 116: Turgon relocates his people from Nevrast to Gondolin

Since one of the few things known about Pengolodh is that he was born in Nevrast, I chosen YS 78 as a time when he is approaching maturity but still a young man.

Pengolodh's ruined page was done on Bristol vellum with acrylics, ink, and gold leaf. I tried to replicate the process he would have gone through as much as possible. (Except that I started with the illumination; in life, I know better, and I suspect Pengolodh does now too!) I laid out my calligraphy before beginning and let it deteriorate as I worked and Pengolodh would have become increasingly convinced that the page couldn't be salvaged. I didn't plan any of the scribblings and doodles that adorn the rest of the page. I did write "Creator" beforehand; however, I wrote it differently than I usually do in order to best replicate Pengolodh's experience of inventing a sonnet on the spot. Usually, I compose sonnets on the computer, in a table where I can add lines out of order and move them around, if need be, and where I can note the rhyme scheme in the margin and highlight any meter issues as I go along. I also rely almost religiously on a rhyming dictionary to help me in my composition. Sonnets are very difficult for me, so writing one directly to paper felt rather like working without a net--but I think it turned out well. I did make some minor corrections as I worked. If you're curious what the writing journal of a real-life poet-scribe looks like, you can see my working pages for this project here.

The illuminated design is mostly of my own invention; however, the gilded fruit-and-squigglies are borrowed directly from medieval sources. They were very common, and I've always liked them, strange though they may be. (See an example here.) The calligraphy is a hand that I invented to resemble the Tengwar. In truth, I find it bordering on hideous and much prefer the sections done in Pengolodh's "cursive," which in scribe-speak is normal handwriting, and which rathers resembles my own disgustingly neat natural hand.

Finally, line 9 in "Creator" is slightly altered from a line in The Silmarillion, "Of the Silmarils and the Unrest of the Noldor." Pengolodh, of course, would say that this poem is about Eru. Having pointed out this line and its source, I leave it to the reader to decide whether she or he believes him or not.

The List

If your character would have a chance to start anew and with a clean slate, what would he or she do with such a chance? Write a story, poem or create an artwork where this is offered to them or how they execute such a chance.

This story doesn't exactly fit the prompt. But it begged to be written, so I complied.

Read The List

The list was out.

Word of it pounded through the college with a sound and speed like the racing blood in their bodies. The list, the list, the list … Dry mouths wheezed laughter; sweaty palms went unwiped on robes in an attempt to look casual; students hovered in languid clusters and pretended that they didn't care, that in their minds' eyes they didn't see just a wooden door, shut, sealed, and the list upon it, pinned in place with a neat brass tack. They made their way to the headmaster's study under a gentle exertion of force like that which, over time, shifts the courses of rivers: so slight that it can't be perceived as a compulsion, yet is. Fingertips trembled and drummed to hide it as they passed up and down the list in search of a name. Those who weren't on the list remained carefully indifferent. Those were on it suddenly cared.

Pengolodh had none to walk with him. He had the loneliness of any child with the weight of expectation upon him, heavier than a shirt of rings, a subtle, constant weight that held him tighter to the earth and made him lag ever behind his peers. He was the son of two loremasters and his mother a master in illumination as well. Teachers knew his name on the first day of class without having to ask. His papers came back scored as though with ink-black blood that told a story of perpetual disappointment. Teachers called his name without turning from the slate to see who was volunteering to answer. "Pengolodh." It was never a question. The eyes of his peers made him squirm like an organism pinned in place under an anatomist's glass. He longed to free himself, yet to do so would be immolation.

The door to the teachers' hall banged open with such force that it struck the wall behind it. Three boys were ejected in a riot of whoops, leaping from the third stair to the path below. One boy leaped so high that his knees seemed ready to brush his chest and his robes flared high enough that Pengolodh saw his underpants. They paid Pengolodh no mind. They rounded the corner of the healers' college and their voices diminished.

The sun was low, easing herself into the western sea like an old lady into a cold bath. Pengolodh caught a glimpse of her between the buildings before passing into the long shadow of the teachers' hall. His hands were in the pockets of his robes past the wrist. His father hated that and threatened constantly that when Pengolodh next needed new robes, he would order the tailor that they be made without pockets. "Then where shall I keep my quills?" was Pengolodh's tepid protest. "You are an imaginative boy," his father said. "You will think of something." Pengolodh played with the inner seams, picking at the stitches until they unraveled; pulled them and delighting in the feel of the two halves of material unzipping from each other. Delighting in the crimped string that he extracted as a result. He would have to think of something for his quills now, for they would fall through his pockets and drop down his leg to the ground.

He wrapped the crimped string around his fingers as he climbed the stairs.

Most of the children had come and gone already by now. The slow compulsion upon them was not stronger than it was upon Pengolodh--perhaps the opposite--but there was less in the way of resistance. Pengolodh had raised a mountain to guard against the wind. He'd had to. Rivers could not shift overnight without first unmaking the world upon which they flowed.

It was a familiar climb to the fourth floor and the headmaster's study at the end of it. Pengolodh had made it three times now, each at the end of three years of the Sun, each culminating in disappointment, disappointment that remained vague and intangible. Maybe if there was a second list … a list of those who didn't make it, he often thought. Maybe … But there was not. And so, for three years now, the disappointment was a gradual settling upon his already weight-wearied shoulders, for maybe he'd overlooked his name? Or been overlooked? The exhaustion of the day the list was posted was less that initial plunge of disappoint when--after running his fingers ten times down the list, twelve, twenty--his name did not appear on it. The exhaustion came from nurturing that tiny flame of hope over the entirety of the summer holiday, a leaping of the heart at every knock upon the door, a straining of the ears for those words: "Master Sailaheru, there has been a mistake. You see, your son Pengolodh was left off the list, inadvertently of course, and we only realized when he did not report to his master's study for the books he shall require for his apprenticeship--"

Pengolodh mounted the final stair. There it was. The door, at the end of the long hallway. The list, centered upon the door and held in place by a single bright brass tack. Pengolodh swallowed hard and started down the hall. He had wrapped the string from his pocket so tightly around his fingers that the tips of them had gone purple and, when his fingers rested lightly upon the list to scan it for his name, there wasn't much feeling left there. It was like running his fingers down a column of air.

Twenty were chosen each year. Three times, Pengolodh had been rejected. Last year, the list had only contained nineteen names (Pengolodh had counted them, five times); they would have rather chosen no one than him. Three times, his mother--brutally practical--had reminded him that the list was only permitted to hold the names of those who had reached the point in that individual's basic education when it was believed that he or she would not progress any further without a master's individualized guidance. She didn't look up from her work when she said it. She had been chosen in her first year, one of the only illuminators who could make such a claim.

"It is a compliment, Pengolodh," she told him, three times, yet he knew full well that she didn't regard her own hasty choosing as an insult but, rather, an indication of natural talent. Which he was clearly lacking.

He scanned the list once. He was not on it. His stomach sagged as though he'd swallowed a great iron ball. He scanned it again. Perhaps he'd missed--

He had. There he was. His finger stopped on his name. He read it, twice. Again. Just to be sure. Yes, it was there. He was there. Yes, he was accepted.

He straightened and wet his lips and looked around. All of the other students and teachers had gone home for the night. There was no one to celebrate his acceptance, no one to see the change upon his face that, yes, at last, he could admit that he cared which names were on the list. And, tonight, his parents had a meeting for the historian's guild and wouldn't be home to celebrate either. He'd heard them talking about how someone from Lord Macalaurë Fëanárion's camp would be there to participate in a debate about the construction of the Ainulindalë stories, so they'd be out late, and they wouldn't see his acceptance as an apprentice (which was inevitable anyway, given his bloodline) as an excuse for surpassing his bedtime.

There was a wild feeling inside of him that longed to whoop and jump like the boys he'd seen earlier. It struggled and kicked within him to free itself. He whirled around fully on his heel and banged his fist three quick times into the wall with triumph. He had to bite his lip not to shout. The feeling was surging until he felt that he was crackling with electricity that, if it was not dispelled, would drive his heart into a fury beyond what even an immortal body could contain. He imagined the breezy relief of the flight across the sea to Mandos as his body cooled beneath the list.

Trembling fingers found a blank sheet of paper tucked in his lessonbook and a quill. A pot of black ink. He watched himself with detached interest, like he watched the dancers at the Gates of Summer, his mind never fully able to comprehend where all their energy came from, even though he liked to watch them.

He knew the names of each of his classmates. He'd learned them all so that if he was ever spoken to or invited somewhere, then he was not left humiliated by his inability to even greet his savior by name. He memorized the names of people like he memorized the names on maps or timelines. They loomed large to him. But now he felt as though he stood on the instructor's dais at the front of the room. He felt like he looked over the tops of their head and that his voice--though no louder--was more powerful than their own. At last, he thought. At last …

The quill slashed short black strokes not at all like his own handwriting. It wasn't beautiful at all, but that was good. Even beneath the wildness was a murmuring fear of discovery. Eyes cast quickly about him, but he was still alone. There were forty-seven names on the page; forty-seven names not accepted and beneath his own. He knew every one. With an extra brass tack tucked away on the side of the doorframe, he pressed his list into the door.

Chapter End Notes

The personal reflection that inspired this story can be read on my website.

Song of Creation Denied and Thwarted

-Leonard Bernstein, American composer

Write a story, poem or create an artwork where this quote is validated.

Please be forewarned that this vignette includes a brief mention of miscarriage. If you are sensitive to such subjects, please use care.

This story is deeply informed by the short story The Yellow Wall-Paper by Charlotte Perkins Gilman.

Read Song of Creation Denied and Thwarted

After being shouted at already by his father for being careless with the door, Pengolodh let it shut almost silently behind him. He did not mean to overhear the conversation in the parlor, and had he been less conscious of not thundering up the stairs (for which he had also been shouted at), then maybe he would have ascended fast enough not to notice what was being said. As it was, though, rolling his feet carefully, riser after riser, he heard enough to make his step falter into shameless eavesdropping.

"She wants her paints. She says she will only add color to what she had already done in ink before--" His father's voice, stern but melting into some more vulnerable at the end, trailing away, as he never allowed happen. This is what made Pengolodh's step falter.

"I'm afraid that is not a good idea." The droning voice of the healer, perhaps bored already with these ambitious Noldorin craftswomen. "I understand her desire for expression, but keep the paints crated. I have brought --"

There was a rustling of something being taken from a box.

"A harp? My wife has never played--"

"It is a way to release the emotion without jeopardizing her health. She is frail, Sailaheru." Pengolodh's foot--poised above the next riser--stayed itself in midair. There was something almost fraternal in the use of his father's unadorned first name. Few called him that, save Pengolodh's mother and others trusted in his father's confidence. He had never known that the healer--though he came on recommendation of Lord Turukáno himself--had achieved such … yet, Pengolodh told himself, it was logical, for the healer had been here well past the decent hours for a week now. A week today, exactly.

"This was an ordeal for her, Sailaheru. I cannot emphasize this enough. She does not need to work; she needs to rest, and while it is fair of her to expect to have outlet for her emotions, then that must not come as writing or painting. She has borne two children now. The failings of women are very different than our own failings, and we must understand what she needs right now."

"But she says--"

"She would. She would. But she is gone weak, and we must do what we must to make her strong again."

Pengolodh let his foot settle on the next riser, but he did not lift his weight. He swallowed hard. He could feel his pulse pounding where he clutched the banister. Is that true? he wondered. Is Amil truly weak? He'd never thought of her that way, certainly. A place as her apprentice was the envy and dread of all the illumination students, and when she stood to speak at the historian's guild, silence fell abrupt as a stone from a palm suddenly opened. Even those wont to argue ceased speaking, mid-sentence. Pengolodh had seen it himself. His father's approval was a rarely earned prize, but Amil's--

The healer had been trained in Lórien, one of the few that had not gone over with the Fëanárians. He had that authority, and his voice dripped with it. Pengolodh felt his former impressions shift ever so slightly.

"I just do not know …" There was something naked in his father's voice. Pengolodh felt as though he was gazing in at something opened on the anatomist's table that he should never have to see in a man alive. Pengolodh let his next foot fall. He wished he had not lingered so. He found it hard to imagine that voice shouting at him.

"Of course you do not. We have studied it. We know. It is the female constitution. She is weakened when she bears children. She has done so twice now, and lost one--"

Mindless of the noise, Pengolodh took the last three stairs and, in long strides, arrived at his room, slammed the door, fell against it--his pounding heart obscuring any further sound from the parlor downstairs--slid to the floor, remained there until the dark dripped down fully into the west, till night came and he slept where he sat.

He awakened later to music played upon the harp. His mother could not play. Other Noldorin girls in Valinor, he knew, had studied at weaving and music, but Coinúrë walked for an hour each day, up the slopes of Taniquetil, to get underfoot at Manwë's scriptorium until they plunked her down at a desk of her own, with paints and vellum and brushes of her own, to keep her out of the way. The story was not romantic when she told it. It was described in the same tone as those who had crossed the Ice told of rescuing rotting fruit from the bottoms of backpacks and mixing it with ice to eat.

The notes were discordant, expected from one who understood how many things fit together but not notes of music: gagging chords and huge splaying glissandos and notes that toppled one upon the other in wincing disarray. Pengolodh lifted his hands but could not force them down upon his ears. His fingertips trembled at his temples. There was an emotion in the song, but it was an emotion for which no word had ever been uttered, an emotion known only to those whose imaginations reeled and blood surged and felt that they would burst but for an act of creation; it was the emotion of that creation denied and thwarted. He was not surprised when the song ended with the sound of shattering wood.

Look

What does it say? What is your reaction?

Capture this moment in a story, poem or piece of art.

This story is set shortly after Stars of the Lesser, although one need not be familiar with "Stars" in order to read this. Curufin and Maedhros are visiting Nevrast to meet with Turgon and have brought Celebrimbor, who is close in age to--though a bit older than--Pengolodh.

Read Look

Pengolodh."

Pengolodh sat under a gnarled, wind-bowed tree, facing the sea. A book was spread open in his lap, his fingers pressing on the margins of the pages to keep them from being turned by the wind, his lips moving in almost-whispers, as he had a habit of doing while reading alone. At first, he credited the voice to his imagination, to the wind, to the barely spoken words on his lips. Spring had arrived by the calendar alone; the skies remained overcast and the winds off the sea bitter. Pengolodh knew that he was alone. He was reading outside, despite the wind and cold, to assure it.

"Hey. Pengolodh."

The voice was louder this time and it was most certainly a voice. Feeling childishly superstitious, Pengolodh's eyes flew up to the branches that dipped and creaked overhead. He had heard that trees sometimes spoke in this land, but its tired gray branches betrayed nothing. It only nodded harder as the winds picked up.

"It's me," said the voice. "Celebrimbor."

Pengolodh had been shivering inside the snug wrappings of his cloak but abruptly stopped, even as his heart leaped in his chest. He'd been less frightened of the speaking tree.

"Don't turn around. You don't have to. I know you don't want to see me."

"I never said that," Pengolodh said. The wind took his voice, and he didn't bother repeating himself. By the play of Celebrimbor's voice on the wind, he realized that the other boy was sitting beneath the tree as well, on the opposite side, back-to-back with Pengolodh and with the ancient trunk between them.

But Celebrimbor must have heard him anyway. He laughed. "Your people never want to see my people."

"I think," Pengolodh began, intending to finish with a stern you should leave. He even squared his shoulders, intentionally impersonating his father, as though that would grant him the courage to say it. But his tongue lay, insensate as a slop of pudding in a porcelain bowl, leaving only, I think.

"Of course you do. That is why I am here. Look, Pengolodh--"

"I don't want to look." It was childish and literal but out before he could help himself. He fixed his gaze more firmly on the churning gray sea, as though to reinforce within himself the notion that, no, indeed, he did not wish to look at Celebrimbor. He could imagine, though, the boy sitting on the opposite side of the tree as he, wrenched around to catch a glimpse of Pengolodh's cloaked shoulder (shivering again), the edge of his book, a slick whip of Noldorin-black hair.

"Sure you do. You intend to be a loremaster. You can't do that with your eyes closed; you might as well write poetry."

"I do, sometimes."

"So do I, but it is a different matter than lore, Pengolodh, and you right know it. But, yes, I came here to tell you that there are things you don't know, and I mean to tell them, if you would listen."

"I am sure that there are many things I don't know." Pengolodh was proud of the mild, almost indifferent, tone of his voice; less proud when he realized that he didn't have a suitably barbed conclusion to that fact. Celebrimbor was right: He intended to be a loremaster and so to seek answers to what he did not know. Intended as a dissuasion, his remark instead seemed more an invitation.

"Yes!" said Celebrimbor, apparently hearing it the same. "And there is much that I can tell you that, otherwise, among your own people, you will never learn."

An image flashed in his mind of Fëanáro, the grandfather of Celebrimbor, in his workshop. Light floated in the cup of his hands. Secret knowledge, thought Pengolodh, imagining such lore passed son to son, and now to him? His pulse quickened to be thought so special. But he was not a craftsman, and such secrets would be useless to him. Furthermore, it was universally agreed that Fëanáro had been dreadfully wrong in pursuing some of the knowledge that he had, that some knowledge, rightfully, lay beyond the bounds of proper inquiry. There was courage to be found, his father often said, in not fearing to find and acknowledge one's limits. Celebrimbor would probably laugh at that, and the thought of Celebrimbor's laughter, of the beauty of his face when he smiled (and, oh, he was said to be but a shadow of his grandfather and Fëanáro--could I ever have withstood Fëanáro?) made him want to believe Sailaheru's words all the more.

"I don't want it," he said of the secret knowledge. He imagined what would have come to pass had the great (supposedly great) Fëanáro had the same courage. Pengolodh would not be sitting beneath a twisted, near-dead tree in a half-frozen land but, rather, beneath a different sort of tree, the kind that bore fruit and leaves year-round, in a (he imagined) dark blue silken tunic with silver embroidery at the neckline and sleeves. Though Celebrimbor said nothing in answer, he reiterated, "I don't."

"Pengolodh, I believe that you don't want it, but by the ethics of your one-day profession, that you are required to hear it. Anyhow, I will tell you just one thing now because I am not supposed to be here, and my father will be returning soon and will not like to find me missing. You can come to my father's camp if you want to hear more. Just have the guards send for me; you do not even have to come inside, and we can speak--you and I--across the invisible boundary of yours and mine. Else, I will return to you when I can and say what time permits, which will not be a lot. But, over the years, perhaps it will all eventually be said." There was a moment of silence in which Pengolodh imagined him drawing a deep breath. "My uncle, Maedhros, did not forsake your lord's brother. That is the first and all I can say now. Farewell, Pengolodh, for now."

Pengolodh did not turn from the tree. His numb fingers clutched the sides of the book; his mind imagined the long-limbed Fëanárion racing back to his father's camp with a helpful wind at his back, his black hair streaming against the sunless gray sky like a banner.

Truth

Read Truth

He was out on the rocks, as his note had said he would be. Even from far down the beach, I could see him: a tall figure, leaping from rock to rock with a physicality I did not possess, wearing a pale blue tunic much too large for him, and that black hair, as always unfettered, playing with the wind. As I drew closer, I saw his boots had been kicked off in the sand and were being nudged by the rising tide. I ignored them--let the sea take them and temper his confidence!--and walked to the brink of the rocks where he played.

"You came," he said upon turning and seeing me. His nose was running from the cold and the damp, and he sniffled loudly and wiped it with the back of his hand. He grinned at me.

I proffered a handkerchief. "Here."

He took it and squinted at the monogram embroidered in the corner with three colors of thread. "Oh, I could not. It is yours."

"I don't want you handling my father's book with your hands …" I fumbled for a polite way to allude to his crude behavior and had to settle for, "Like that," before arriving suddenly at the word, "Besmirched."

"You have brought it then?"

"Yes. Did I not say I would?"

"Sure you did, but your father doesn't seem the sort to allow his original volumes out of the house, much less into the hands of a traitor by the sea." His hands were busy with my handkerchief, wiping each finger meticulously clean. The differences between our houses are what they are, but we were both the sons of artisans and knew the worth of the book that formed a lump beneath my cloak.

"He does not know that I removed it," I said and, with Celebrimbor's wide-eyed delight, immediately regretted admitting.

"There is hope for you, Pengolodh!" he crowed.

"I wish you wouldn't say that. There is hope for me, yes, but not of the sort that you desire."

I had rivals among my cohort in Nevrast, of course, but none filled me with implacable irritation like Celebrimbor of Himlad, despite the fact that Celebrimbor and I competed in nothing. He only barely alluded to his work and his studies and, aside from the afternoon that I had discovered him catching sea creatures with hopes of discovering their source of light, he had shown me none of it. None of my people or his were even aware that we knew each other. His father's camp hovered at the verge of what Lord Turgon would tolerate--Celebrimbor's uncle having departed long before--and all in Nevrast burned with the unspoken wish that Curufin and his son and their retinue would just go away. So it was not as though he cultivated anything resembling favor; even Lord Turgon's sister--widely believed to be the reason that the Fëanorians lingered--did not seem to notice Celebrimbor, and I had never trusted her, besides. But there was something … I was reminded of how magnets held wrong will fly apart. There is something inherent in their nature that they cannot tolerate the other. I suppose that's how it was with Celebrimbor and me.

He seated himself on the rocks, apparently without mind that his trousers would be soaked through. He held out his hands for the book, and I made vague noises of caution that he ignored with a robust, "I know! I know! Let me see it!" I placed the book in his hands.

With careful haste, he opened to the first page. "So this is--" There he stopped. His fingers lifted from the corners of the pages as though afraid his touch alone might mar them. I saw his chest rise with a quick gasp of surprise. "This is what your people think of my people."

"It is the story of the Exile, yes," I said.

"These illuminations … they are beautiful."

Pride quickened in my heart at that. My mother's work: enough to arrest even a Fëanorian, who had spent his life amid objects of great beauty without ever deriving the meaning of them. With the most beautiful light in Arda to look upon daily, his people had turned into traitors and slayers of kin. Slowly, he turned the pages. He was ignoring the words, for now, done in my father's impeccable hand, to wonder at the illuminations and the miniatures. There was his grandfather upon the palace stairs at Tirion, there was the host before the gate, there was Manwë's herald and the long road diminishing between the Pelóri and the faint blush of lamplight from Alqualondë beyond.

"You see," I said triumphantly as he paged past the scenes of Alqualondë without pausing to argue, "we do know something of it." There was his uncle--made obvious by his golden hair and the eight-point star upon his raiment--with a Telerin maiden speared through on his sword. The tidy black script told the tale of it: how we had "aided" our kin when they were the aggressors and how we were betrayed as reward for our damnable loyalty. It was our shame as a people, but my father's hand never wavered, never changed, in the telling of it.

"Hmmm" was his only reply.

He reached the scenes from Losgar. My mother had devoted the entire verso to the painting of it, and my father's letters filled the page opposite. There he paused. He read every word, stopping often to consult the painting and holding his place in the text with a finger that hovered just slightly over the page. I listened to the tireless roaring of the sea and watched him read.

He shut the book and handed it back to me.

"It is a beautiful book, Pengolodh," he said. "I know of your mother; I have heard my father speak of her, and he always does so in praise. Being as they were close in age and ability, she was often seated opposite him in debates in Valinor, and she chose to study with Elemmire, knowing that my grandfather would have taken her as an apprentice also, had she asked. As it was, my grandfather never sought apprentices, or so I'm told. Seeing her work, it confirms and exceeds my every expectation. I have heard my father speak of your father as well--" He stopped there and bit his lips between his teeth as though forcibly restraining himself from speaking further.

"But it is full of lies," he said after a moment. His eyes--silver like starlight--burned into mine. "It is a book of lies. None of your people could know what happened at Losgar. You were not there--was not your absence the entire point? And I will not argue in favor of what was done that day but this--" he stabbed his finger at the book that I sheltered beneath my cloak--"is lies! It is a book of beautiful lies! I cannot believe your mother--"

He composed himself with difficulty. My heart thundered in my chest, and I had to force my tongue against the back of my teeth to keep from speaking, but I was determined that he should reveal what I knew must be true of him. I desired greatly the excuse to loathe him, he who was as skilled, eloquent, and beautiful as his illustrious bloodline would suggest. I wanted evidence of the haughty savagery that had shown itself in his bloodline as well. At last, he said, "I cannot believe your mother would squander her talents--her considerable talents--on a book of lies that will soon enough be discredited. All of the beauty in this book is wasted on its hideous words."

He rose from the rock and, rescuing his boots from the edge of the surf, pulled them on. Did his hands tremble? He had a more difficult time with the boots than he should. Nor did he seem to notice that they were sodden through.

"I hope that you will fix what has been done between our people, Pengolodh. I will tell you the truth, if you will only listen, and I trust you will write what I tell you with justice to your people and to me, your friend."

I started. Friend? My tongue had loosened but, with that single word, all hope of letting it sculpt an eloquent stream of speech that would render Celebrimbor silent and chastised abruptly died. My jaw flapped open and shut and, at last, I managed to blurt out, "Elenwë died! And others …"

"I know!" shouted Celebrimbor. "I know I know! I do not and have never denied it, or the wrongness of what was done! I am not asking you to sweep sand over that truth, but neither should you sweep sand over the truth that we are not evil villains but were only doing what we thought had to be done! And that decision was far from unanimous. Your book, I note, does not mention that my Uncle Maedhros stood aside, and with him a contingent of like-minded folk, although I have told you that truth. Do your people not know the value of marginalia, or do you let one man's flawed story stand, unchallenged, for the whole of time? Your mother's painting shows the play of fire on Maedhros's hair as he draws back his arrow and aims at the ships! Your book is wrong because you were not there, but you will pretend that you were there in order to take empty solace in the lie that my grandfather's people thought of yours only with malice. That pardons your hatred of us. You are allying against the wrong enemy, Pengolodh."

I had not even been born when my parents shivered at Araman, awaiting the return of the ships from Losgar. Yet a thought of that night imprinted my memory as surely as if I had been, as surely as if I had been standing, silent and unmoving, among the Fëanorians on the opposite shore. I watched them dip their arrows in the fuel and one of them--in my mind, it was always the younger twin--race down their length, dragging a torch over the tips of the arrows before stopping at the end to light his own. What was on their faces, as they drew back the arrows and aimed at the sails swelled with wind enough to carry them with ease back to the opposite shore? As it was, the wind teased the flames to life, let them bite faster at the tender wood until only a scrim of ash remained upon the water. Now I was on the opposite shore with my parents, watching the sky flush scarlet with a hue like lividity rising to an angry face. What was on the faces of the Fëanorians? I could never tell. The terror in my heart at the swelling light in the east was what placed the malice-twisted expressions upon their faces.

Now there was one before me. He had been but a small boy when the ships burned at Losgar, but his face twisted with anything but malice. Yet what did he ask me to do? Turn my back on the wall bordering the sea where, before even the first building was raised in Nevrast, our sculptors had carefully written each name of the lost? And offer my hand in friendship--to what? To follow Truth's beautiful, shining lantern, but to what ruinous end?

Chapter End Notes

As always, the thoughts and experiences that I used in response to the prompt to construct this story can be found on my website.

The Mountains and the Sea

Write down three to five adjectives that describe why you find that person admirable.

Now write the opposites of those three to five adjectives.

Write or draw something from the point-of-view of a character who displays some or all of the "negative" adjectives on your second list.

I chose as my three positive traits honesty, empathy, and selflessness. For their foils, I chose dishonesty, indifference, and greed.

Read The Mountains and the Sea

The girl flung herself down on the grass near to me and commenced hiccoughing into her folded arms. It was a particularly lovely day, passing unseen, for, despite choosing to pass the day's study outside of doors, I'd determinedly kept my head bent over my book and didn't grant any mind to the cerulean sky or the benevolent gaze of the sun or the wispy clouds being pulled apart by the delicate breeze or any of the other poetical hogslop typically applied to days like this.

When she flung herself into the grass, I clutched my book tighter and pulled my elbows into my body, like I might collapse myself into a speck invisible to her eyes if I squeezed tight enough. There was a whole vast hillside upon which to fling oneself--unoccupied save for myself--but she chose this spot, where I had no choice but to overhear her escalating sobs and the dull thumps of her tiny fists beating the earth. I shrunk smaller yet and wished for that gentle breeze to whisk me away, anywhere but here.

The trouble was that I'd chosen here in the first place for the tendency this day of Nevrast to behave in a manner much like that of the weeping girl proximate me. I was not the sort to become whimsical at the prospect of studying out of doors: the clouds sliding across the Sun created uneven, unexpected shadows and the wind toyed with my pages. But I'd been unable to work in the city. If marble and stone could wail, Nevrast would be a cacophony. Such was always the way when men were called to war.

I knew that she had flung herself intentionally near to me in hopes of exciting my pity. I knew that I was supposed to ask whatever was the matter and to put on a voice of syrupy sympathy. I hugged my elbows tighter to my body and did not speak. The only emotion that she incited in me was a rousing irritation that her sobs were scattering my thoughts like pebbles thrown into the midst of a flock of gulls, and I had an exam the next day. I was never much for playacting and hardly wished to develop an affinity for it now.

"It's terrible …" she mewled.

I heard myself agreeing that it was. That required no playacting; a whole page I had read now and every word slipped right from my brain as though they came greased. Greased by tears, most likely, and unnecessarily strident sobbing. She was telling me that her betrothed had volunteered. She was telling me about the assault on the lords to the north as though I didn't already know about it--but, then, I didn't know much, did I? They had broken upon the armies of King Fingolfin, she told me, but isolated bands had escaped and come as far as Ivrin, and they would not come here, most likely--not with Ered Wethrin to cross--but the men of Nevrast had roused at the chance for heroics and-- There she shrugged. "He volunteered," she said. Her sobbing had stopped.

"Yes, yes," I said impatiently. I knew these things, though I had tried not to hear. I preferred them to come to me distilled as legends and stories, upon the pages of books, with men in bright armor astride chargers that galloped in the margins. But I had heard. "You are a scribe!" my mother had said. "What are you to do there?" She sounded aghast at the thought.

"I can record the deeds in song, if nothing else," replied my father, although all knew that he was Lord Turukáno's historian for reason of being a mediocre poet. Then, laughing and indignant, "I can sit astride a horse you know!"

"But I do believe it requires more than that, love."

"I suppose I should be happy for him," the girl near me was saying. "He could feature in your books someday." Trembling fingers flicked the tears from her cheeks. "He is braver than me, certainly. I doubt that I could go to war, much less volunteer--" She squared her shoulders and turned her face to the sun. If a tower suddenly sprang up beneath her--a tower crawling with vines and roses--she would make a very suitable illuminated page border for an epic romance: the hero at war, the stout-hearted lady who remained in wait--

"Not necessarily," I heard myself mutter. "There is bravery in waiting." But she did not hear me. She was already rising and running back toward the city, her mind probably filled with ridiculous images of the sunlight on their armor and ladies casting roses beneath the feet of their high-stepping horses … I hugged my elbows closer and returned to my book.

Hemmed as we were between the mountains and the sea, who had expected this? It was supposed to be safe here; another Valinor, I had once heard my parents whisper. Another Valinor, a place of beauty and peace. We were not supposed to march to war. How would there be beauty and peace if we marched to war? If we learned that blood began as cadmium and dried as alizarin? How would there be beauty and peace if we did not march to war? Hemmed as we were, between the mountains and the sea?

Chapter End Notes

The battle to which the unnamed woman alludes is the Dagor Aglareb, or the Glorious Battle. It's not "canon" that the Elves of Nevrast offered help in this battle, but why not?

For the personal musings that inspired this piece, please see my website.

(1) Comment by oshun for Illuminations [Ch 1]

That's great! But you weasled out--where is the illumination for the piece! Tsk. Tsk!

Re: (1) Comment by oshun for Illuminations [Ch 1]

Maybe I'll get to it someday! :D The technique I describe of the cadmium red with the light work in shell gold is real, and one thing that's on my Must Try list. Since I plan to illuminate some of my writings, maybe I'll try it out for this one. ;)

(2) Comment by Angelica for Illuminations [Ch 1]

Beautiful fire.

Everything sounds so monastic (the scriptorium, the vellum, the hourglass, the illuminations) that it got me thinking about Elvish inventions. I remember reading somewhere in HoME XII -if I'm not wrong- that in Aman Elves didn't need to put things down in writing since they could remember everything but once in M-e they realized they could die and so started writing the important stuff so it would survive them. Didn't they know about the printing press? Or they thought beauty in the texts was more important than expediency? And the lighting? No Feanorian lamps for Turgon in Nevrast?

PS: Have you read Umberto Eco's The Name of the Rose?

Re: (2) Comment by Angelica for Illuminations [Ch 1]

Good observation, Angelica ... I\'m working a lot of my studies in the scribal arts into this as well. :) I\'ve always imagined that the Noldor would have an appreciation for illuminated manuscripts: turning something functional into something beautiful. I\'ve never given much thought to the printing press; I would have a hard time believing that the Noldor would be incapable of thinking of *something* to allow them to mass-produce written works, but special documents might continue to be hand-done and illuminated. This was done in period, actually; even after the invention of the printing press, illuminated manuscripts continued. (In fact, became more elaborate in many cases!)

My own thoughts regarding Elves and books (because I gave this thought when writing AMC, since Feanor and Maedhros are always reading and writing books) is that, while books might not have been as common in Aman (that rhymes! ;), I have a hard time believing that they didn\'t exist at all. Writing things down is still a tremendously practical way to share information; this is the explanation used in AMC for why Feanor puts most of his teachings into books. He is something of a oddity in that, not surprisingly. ;) This is, of course, my own interpretation; it is not \"canonical\" in any way.

Re lighting: *Nothing* beats natural lighting for painting! :) When I was still working on miniatures, I would sometimes paint by lamplight inside-of-doors and then go out the next day to work in the sunlight and have to redo most of the previous day\'s work because the colors, under natural light, were all wrong. So that\'s what I\'m going with here; that Feanorian lamps, with their bluish tinge, aren\'t ideal for painting by, at least when natural light is an option.

Incidentally, when Pengolodh\'s father snarks about loremasters who work at night, it\'s Feanor he\'s talking about. ;) Though I don\'t know if their vitriol extends as far as to deny themselves useful technology, just because he invented it!

(3) Comment by SurgicalSteel for Illuminations [Ch 1]

OOooo, I like the imagery in this!

Re: (3) Comment by SurgicalSteel for Illuminations [Ch 1]

Thank you! A lot of what Pengolodh is experiencing, I have experienced (because I am also studying medieval scribal arts), so the images were readily available. :)

(4) Comment by SurgicalSteel for Illuminations [Ch 2]

Oh, I like this - famine and disease are no less dangerous in their way than combat. I like this a lot!

Re: (4) Comment by SurgicalSteel for Illuminations [Ch 2]

Somehow, that does not surprise me about the famine and the disease. ;) But thank you! I\'m so glad that you liked it! :D

(5) Comment by Rhapsody for Illuminations [Ch 1]

Yay, more Pengolodh written from you and what a fabulous start! The scribe to be starting as a servant lad, hoping and wishing to be one of them these days. I did not have an idea how the hierarchy would be for this trade, but this was a great brief introduction. He is still so curious, isn't he? I just love how he carefully handles that scroll, how he marvels at the way the scroll is written, but the icing of the cake for me is at the end when the sun rises and the writings (of Fëanor?) come to life.

Re: (5) Comment by Rhapsody for Illuminations [Ch 1]

Ah, Rhapsy, you would pick up that those manuscripts were Feanor\'s! ;) I\'m not going to keep entirely with the medieval scribal system here because, then, everyone specialized immensely (ten people might work on a single manuscript!), but Elves have a lifetime to learn how to mix paint, do calligraphy, *and* paint illuminations! ;) But I am very much inspired by my scribal arts studies, as a few people have noticed.

Btw, Pengolodh\'s marveling over the scroll certainly comes from my own life. ;)

(6) Comment by SurgicalSteel for Illuminations [Ch 3]

There is something quite nice about waking up to snow when you don't have to go out in it. And oh, do I know that ridiculous look of wading through the snow - we got 26 inches in central Maine about a week and a half ago, and wading through thigh high snow drifts to get in was interesting, to say the least. ;)

On the other hand, I know the feeling of relief at having an important exam rescheduled. Many years ago, my MCAT was rescheduled because a Cat 5 hurricane was predicted to hit the Gulf Coast. It took a southward turn at the last minute and hit Mexico instead - but every pre-med student in Houston and Galveston got an extra week to prepare, which was nice. :)

I liked this!

Re: (6) Comment by SurgicalSteel for Illuminations [Ch 3]

Thank you! :D Btw, I was quite amused during the Maine snowstorm to keep reading the updates on your Gmail away message! A few years ago, we got three feet during one storm, and I do *not* want to repeat the experience of digging out of something like that again! I felt for you, I really did.

I don\'t think I\'ve ever gotten out of anything because of a storm. We did get a tropical storm exactly on my 18th birthday. I still think that was a harbinger! ;)

(7) Comment by Rhapsody for Illuminations [Ch 2]

Oh this is a very interesting insight in the young scribe's inner thoughts, and also in a way you show us how relatively safe Nevrast was compared to the realms in the North. I wonder if scribes would hold such a privileged position there. Also, - unintentional or not - you capture the status of learnt people (loremasters and scribes) as opposed to soldiers who'd risk their own lives to feed their families. Pengolodh's sudden realisation that such young men have families, children compared to his scholarly (and perhaps higher education) portrays that to me. The sacrifices they make, death in war opposed to having your own family starve instead. Yes, they are lucky to have such men willing to able to enlist in the army. This is a very sobering, but also intense vignette.

Re: (7) Comment by Rhapsody for Illuminations [Ch 2]

I think that Nevrast at this point still reflects a degree of naivete in the newly arrived Noldor. They haven\'t quite gotten the hang of \"we\'re not in Valinor anymore, Toto!\" ;) Though I do think that all of the Noldorin realms would recognize the importance of their artists/historians independent of their soldiers, at least to a degree. This certainly occurred in our real-world history, so I figure if French scribes could exist during the Hundred Years\' War, then Noldorin scribes\' duties could have been protected as well. All conjecture, of course.

I\'m happy that you picked up on Pengolodh\'s growing realization of the humanity of the soldiers. This is what I wanted to show with this vignette; he\'s been allowed to live a sheltered life (see earlier note on lingering Noldorin naivete ;) but is coming to terms with the work that others do and understanding one need not be an intellectual to matter. He used to think that those who weren\'t smart or motivated enough for intellectual pursuits didn\'t matter much, but that view is changing; he is coming to see them as more like him than not and to realize that, just as they might not be able to do what he does, neither can he do what they do.

(8) Comment by Rhapsody for Illuminations [Ch 3]

Now that is a lovely awakening: snow combined with the sun rising, quite magical indeed. And for the young elf it comes with the combination of a day off! Lucky him.

Re: (8) Comment by Rhapsody for Illuminations [Ch 3]

A snowy morning just looks different than a regular morning; the quality of light is completely changed. (Nighttime is even better! :) It\'s beautiful ... until I have to go out in it. Then I don\'t like it so much!

Thank you for the reviews, Rhapsody! *hugs*

(9) Comment by whitewave for Illuminations [Ch 1]

Pengolodh is a fascinating subject for a character study: it would be a treat to get under his skin and see why and how he wrote what he wrote, his sympathies, his motivations, etc. And you do character studies so well so I'm bracing myself for another delightful dive into ME with my "Dawn Felagund" glasses. ;-)

Re: (9) Comment by whitewave for Illuminations [Ch 1]

Thank you, Jenny! I\'d imagine they\'re some strange glasses! :D I find Pengolodh so fascinating; he\'s there, but he\'s not at the same time. Back before Oshun was writing a bio for each month\'s character, we featured Pengolodh one month, and I did some quick research to have some facts about him to post in the newsletter. He\'s mentioned probably 100 times in the books ... but only *twice* about his actual life. (And one was in BoLT, so how much that counts, I don\'t know.) The rest is \"Quoth Pengolodh ...\" or \"Pengolodh wrote ...\" It makes me ask: Who is this guy? He\'s certainly one of the most important characters to the Silm, and he\'s utterly invisble.

So I hope his character study does not disappoint. :) I doubt he\'ll be as fiesty as the Feanorians, but I think he\'ll raise some questions nonetheless!

(10) Comment by whitewave for Illuminations [Ch 2]

I found the scene of the army recruitment day particularly moving. It's a good glimpse into the more pragmatic, not-so-charmed lives of the "ordinary" elves, though it doesn't diminish my fascination with them.

My favorite lines: "We are lucky," he said aloud, though he did not know who we was any longer...He wondered if they thought to die of rot from a spear wound in the gut was better than to slowly perish of hunger. He wondered if they imagined at all.

Re: (10) Comment by whitewave for Illuminations [Ch 2]

Thank you! Surgical Steel like that line too, though I think that\'s because she likes when I break fanon and kill off Elves with peritonitis. ;) I wanted this scene to sort of continue the discussion on the Yahoo! list where the Elven realms are grittier and nowhere-near-perfect-as-fanon-would-have-it. And it\'s also a point where Pengolodh starts to grow up, to move beyond his sheltered life to begin to *see* the world around him. Or that\'s what I was trying to do. :)

(11) Comment by whitewave for Illuminations [Ch 3]

What a nice break for Pengolodh! Found myself smiling at your note about the Valinorean lamp. It's amazing how you use small and deceptively simple details like that meets the prompt theme with every with every chapter. I can't help but agree with Pengolodh in what made him the happiest for this chapter (and maybe Fëany may even agree with him? ;-)

Re: (11) Comment by whitewave for Illuminations [Ch 3]

Ah, but I think the small details make all the difference in a story! :) Normally, I don\'t even footnote this sort of thing but broke my own rule and answered the canatics before they had the chance to ask: \"Aren\'t they called *Feanorian* lamps?\"

I think Feanor would agree with Penny in some regards too. He actually has a forbidden-fruit sort of fascination with the Feanorians that started in my story for Pandemonium last year \"Stars of the Lesser.\" His curiosity makes him more like Feanor than his own father, which of course creates moral quandries. But I\'m on the verge of spoiling my own story now ... ;)

Thank you again for all the reviews! :D

(12) Comment by pandemonium_213 for Illuminations [Ch 3]

These studies -- like miniature portraits -- of Pengolodh are each and every one little gems, Dawn. In fact, I'm visualizing these each as illuminations! I was especially taken by the precious parchment from Aman with the fiery border. I have to confess that I wondered if Pengolodh -- Pengolodh -- might be hungover with that headache on the snow day, but I have to remember that he may not drink as much as certain of my Firstborn! :^D

This is a really neat idea for a character study, that is, to tie it into BtMeM.

Re: (12) Comment by pandemonium_213 for Illuminations [Ch 3]

Thank you! :D I\'m glad you picked up on the multiple meanings of illuminations here--that was intentional. ;) That parchment with the fiery border, I have been requested to try to illuminate someday; it\'s based on a real technique, so I\'ll give it a try. Though it won\'t compare with Feanor, I hope it will please mortal eyes!

I had to laugh at your assumption of the hangover! No, Pengolodh isn\'t quite that rebellious ... yet. But he will have his moments. After all, there would be no fun in writing these if he was always as steady and dry and boring as he seems in the books!

Thank you for the kind comments; as much as I respect your work, your thoughts on my writing always means a lot to me. :)

(13) Comment by SurgicalSteel for Illuminations [Ch 4]

Poetry, period, is hard for me, so I commend you on this!

I like the first one for this sense of determination. The second - I'm not sure I but that it's about Eru. It somehow 'feels' Feanorian to me, if that makes sense.

Re: (13) Comment by SurgicalSteel for Illuminations [Ch 4]

That absolutely makes sense, and that's what I wanted to convey! (Yay! :D) My version of Pengolodh is intensely curious and thoughtful, and his consideration turns, at times, to those "outside" the safety of what he has come to know as morally right in the followers of Turgon. He is fascinated by those outside Turgon's people despite himself. (I don't know if you've read "Stars of the Lesser" that I wrote in '07 for Pandemonium, but this was sorta the origin of this idea.) So, here, when he realizes that his father speaks of history without ever creating it, he muses on creators ... to be safe, of course, that is Eru, but I have my suspicions otherwise. ;)

(14) Comment by SurgicalSteel for Illuminations [Ch 5]

This reminds me a bit of Match Day. To get into a residency program, you have to go through the Match - you apply, you go interview, and then you submit a rank-ordered list of the programs you liked to the National Residents' Matching Program, and the programs submit their lists of candidates, and every year, mid-March, at noon Eastern time, the results get announced. You can tell immediately who got into a really good program and who didn't by the reactions - the ones who got into good programs are jumping up and down and screaming, the ones who got into merely OK programs are always like 'OK, whatever, I'm pleased to have matched.' They're very blasé. So the differing reactions - the students who care about that list and the ones who don't let themselves care, it reminded me of that.

I liked it!

Re: (14) Comment by SurgicalSteel for Illuminations [Ch 5]

Thank you! :D It always seemed to me, in my school days, that those who didn\'t do well on whatever academic assessment could make it like they just didn\'t care. It always seemed a natural defense to me. Match Day seems to fit that as well. :)

Thank you for both reviews! I really appreciate it! :)

(15) Comment by Rhapsody for Illuminations [Ch 4]

Oh my Dawn, I like the way you tackled this. I angled my head to read the doodles and they are so genuine for a writer/poem when they are composing. The method looks like my notebook. He's very muchly struggling with what he's supposed to say and think as to how he thinks things has happened: questioning himself. His note: this is my father's story and then 'What? Truth, a good just cause, yes but?

It can't be easy being him, deep down knowing that there must be more to it, that a for a good cause doesn't equal that it is the whole truth. It just can't be easy for him to be a child born from exiles with know tangible knowlegde of Aman and what made them leave Valinor. All he has is hearsay basically, then there is this perished elf who intrigues him so much, but has a bad name...

In a nutshelf: I loved this very original piece and I ramble too much!

Re: (15) Comment by Rhapsody for Illuminations [Ch 4]

Thank you, Rhapsy! :) It looks like my notebook too, sometimes; I just start to free-associate and see where it takes me. And I doodle a lot in my margins! :D

It can\'t be easy being him, deep down knowing that there must be more to it

Yes, I can say that as a U.S. citizen, I\'ve done some of the questioning of my country and people and culture that Pengolodh is doing now, and it isn\'t easy. There\'s what you\'re told all of your life and you want so badly to believe, and then there is what *is,* and it reaches a point where one can shove one\'s head deep into the sand and \"drink the Kool-aid\" or one can make the uncomfortable decision of disbelieving a lot of what most everyone else believes. Pengolodh, of course, has a long journey ahead of him yet.

And you do not ramble too much! :) I loved your review, and thank you for it!

(16) Comment by Rhapsody for Illuminations [Ch 5]

Go Pengholod! I do feel for him though that he has so much pressure on his shoulders and that he cannot celebrate this big day with his parents. It just feels to me that he doesn't fit in anywhere: not with his family or his peers. What a lonely life. But then at the end he makes his statement and I can't help to say that I am proud if him rebelling a bit.

Re: (16) Comment by Rhapsody for Illuminations [Ch 5]

Spoken like a true Feanorian, Rhapsody! :D I am definitely trying to set up Pengolodh as a character who has pressure upon him from many different directions. Again, I am pulling a lot from life for this; not from my own life (my parents were always very nonchalant about my academic performance, and that's probably why I did so well in school) but from seeing RL friends who came from families that put tremendous pressure on them. Pengolodh is probably half the kids at the maths & science-focused high school I attended. Thank you for the review! :)

(17) Comment by pandemonium_213 for Illuminations [Ch 4]

A highly imaginative presentation here! Pengolodh's struggle with historical convention comes across so well on Bristol vellum! :^D The transition from the more formal Felagundian Pengolodhian calligraphy to more informal notes is a great touch...just what one expects to find -- as you note -- in a writer's journal or papers.

Heh. I know who I think the "creator" is. Lovely poem. And these verses?

He summoned all his lore and subtle skill

That mind and hands should serve to manifest

The greatest desire of his heart and will,

Then--suddenly still--he allowed to rest.

His hands lay gently folded, gloved with night,

Then, as a blossom opens, revealed Light.

Gorgeous.

Re: (17) Comment by pandemonium_213 for Illuminations [Ch 4]

I would have loved some *real* vellum, but, as they say, people in Hell want ice water, and at $30 a sheet, the Bristol works just fine. ;)

Oddly enough, I like the scribbled writing better than the formal calligraphy, which I think might be the ugliest hand I\'ve ever seen. (I have hope that I can tweak it into something halfway decent-looking! In the meantime, I will assume that, like me, calligraphy is just not Pengolodh\'s strength.

I leave the creator\'s identity up to the reader, though I tend to agree with you. ;) Pengolodh rather gave himself away, I think, when he asked that the page be burned. Burn a poem about Eru?? Not likely!

And thank you for noting those specific lines as your favorites. I love writing sonnets, but they\'re really hard for me, so it is an enormous sense of relief that this one worked for at least one other person! :)

(18) Comment by pandemonium_213 for Illuminations [Ch 5]

This is quite a powerful piece and really, rather searing with its insights into Pengolodh's psychology as you're creating him here.

He had the loneliness of any child with the weight of expectation upon him, heavier than a shirt of rings

What a fantastic way to describe Pengolodh's burden of parental high expectations! In a short piece, you've also provided key background on Pengolodh's parents, too. Master Sailaheru sounds rather overbearing, and his mother's disappointment can still be glimpsed. Subtle writing there, Felagund!

And much more of Pengolodh's character is revealed when we see that he is picked on and how he exacts his revenge with his own list. Definitely the reaction of one who has been bullied. I am intrigued by the potential fallout of Pengolodh's list. Revenge has a tendency to turn around and bite one in the butt.