And Love Grew by polutropos

Fanwork Notes

Fanwork Information

|

Summary: As a host of survivors makes the journey from Sirion to Amon Ereb under Maglor's leadership, old bonds unravel and loyalties crumble. But from the scraps and ruins, new and unlikely bonds take shape. A story of perseverance through suffering. Major Characters: Maglor, Elrond, Elros, Maedhros, Original Character(s), Unnamed Female Canon Character(s) Major Relationships: Elrond & Elros & Maglor, Elrond & Elros Genre: General Challenges: Rating: Teens Warnings: Character Death, Violence (Graphic) |

|

| Chapters: 12 | Word Count: 59, 981 |

| Posted on 6 April 2025 | Updated on 6 April 2025 |

|

This fanwork is a work in progress. | |

Last and Cruellest Slaying

The Silmaril is lost.

Read Last and Cruellest Slaying

The night had been a symphony of violence. The roar of flames eating up thatch roofs. The clatter of combat, the clop of hooves over wooden piers, the slap and break of water as another body found its muddy grave. A thousand voices raised in terror, condemnation, prayer, command.

Now, silence choked the narrow streets of Sirion and dawn bathed the ruined city in a yellow haze.

Dornil’s horse wove a path around smoking debris and toppled merchant carts. The occasional corpse. Dornil did not see them, did not look, for her sight was fixed on the cliffs where the land climbed up from Sirion’s mouths. Against the backdrop of Cape Balar’s rocky thrust frowning in the distance was scored the memory of the jewel’s descent, a gash of silver-gold through the cool grey of morning.

The battle had jerked to a stunned halt, the city holding its breath, watching. Watching the Silmaril take flight and fall— fall, fall, and disappear in the dark waters below.

Those whose lungs still could had heaved a breath of shock and dismay, and then the battle was over. In one beautiful and horrifying moment, both sides had lost.

The first sounds to cut the silence were the confused and terrified sobs of children. Then, the scurrying of feet taking shelter behind whatever roofless, charred walls they could find; the clatter of metal as scattered contingents regrouped. Several had lurched like guttering flames towards an enemy soldier, only to stagger to a halt when they met the other’s eyes. The urge to violence foundered. There was nothing left to fight for.

As the scar of the Silmaril’s path faded from her sight, Dornil remembered her duty. She brought her destrier to a trot, seeking and rallying whatever soldiers of the sons of Fëanor she could find.

“What is the command, lady?” they asked in turn.

“I know not,” she answered. “Hold and wait. Be on your guard.”

At last she caught sight of the standard of Maedhros rising above an unroofed stone wall. She dismounted her horse and called out to the group of soldiers marching under it.

“Captain Lisgon!”

Maedhros’ High Captain turned. The four remaining fingers of his right hand clutched the standard pole so tightly that his bony knuckles were even starker white than his skin, pale as the starlight under which he was born.

“Lady Dornil, I am glad to see you living.”

Dornil swallowed the sudden urge to embrace him. This was no time for sentiment. “What are our orders?” she asked.

Lisgon cleared his throat and gave his answer to the assembled men. “All those on foot who are able are to seek out the injured and bring them to our camp. Both our own men and the people of Sirion, if they can be persuaded. If they will not come, you are to tend their wounds as best you can.”

“And if we are threatened?” Dornil asked.

“Pick up your weapons only if you have no other choice,” he replied.

Dornil bit the flesh of her cheek. “What of those who turned against us, lord?”

Oathbreakers all, condemning their lords to torment. Dornil was certain it was they had aided Lady Elwing’s flight. There had been no way of escape. Not this time. They had made sure of it: no more would fall in vain.

“Only if you have no other choice,” Lisgon repeated. “Go now. You have your orders.”

Slowly, the shock still plain on their faces, the footmen nodded and dispersed.

“Those who are mounted,” Lisgon continued, “are to cry the following message through the streets: that the battle is ended. No weapon will be raised against those with whom we would have been allies, with whom we would now make peace. All are free to remain or to take refuge wherever they see fit. Any resident of Sirion who wishes to follow us will be taken under the protection of Lord Maedhros. Any soldier who wishes to return East and stand against Morgoth has until midday to prepare and assemble at the camp of Fëanor's sons.”

Dornil grimaced. Could it be that even after the night’s hideous slaughter, even after their dearly-bought and fruitless victory, Maedhros was yet set on mercy and repentance? Even for those who had allowed their Lady to lead them headlong into ruin? It was the thief Thingol and his heirs who ought to have repented.

Dornil quenched the thought before it could consume her. It was no use: Caranthir's brothers and their following were all that remained to her. In her grief over the death of her husband and lord, she had sworn to serve Maglor, knowing the esteem in which Caranthir had held him. But after Doriath, to serve Maglor was to serve Maedhros — blindly, mindlessly, a devotion more akin to worship than fealty.

She had no choice but to keep her disdain for the counsels of Maedhros concealed, and she had done so all these long years. And yet, as vengeance slipped further out of reach, she felt the bonds of kinship and fealty unravelling. Not for the first time, she wondered if it would have been better to fall beside her husband in Menegroth.

At the camp on the outskirts of Sirion, men bearing stretchers streamed past the hastily erected tents and wagons, seeking empty patches of ground on which to set their burdens down. Others had not the comfort of a stretcher, but bellowed in pain as they staggered forwards with one arm slung over a fellow soldier’s shoulders. The place reeked of sweat and blood and the delta’s marshy rot.

Maglor passed among the bodies of the wounded and sang as well as his wrecked voice could manage. His throat had not seen such abuse since the Battle of Tears: muscles strained with Song, the soft flesh scraped raw by the heat of smoke and the acid burn of the uncontrollable retching that had seized him when the Silmaril plummeted into the sea. But he had to sing. It was the only way he knew to keep his mind from unravelling into madness.

“Enough.”

Maglor recognised Maedhros’ boot on the grass beside him. He uncurled from his crouch on the grass and stood to face him.

“There will be time for lamentation on the long retreat,” Maedhros said.

Once, Maglor would not have masked the pain of such a brusque dismissal. He might have countered with a biting word of his own. That was before he had borne witness to the erosion of the others’ loyalty to Maedhros. The fallen scraps of respect left behind by Celegorm and Curufin, Amrod and Amras, his own followers — these Maglor gathered and stitched to his heart like a patchwork of devotion. A soft and fraying casement, but protection nonetheless against the sting of little cruelties.

As for speaking to his brother mind-to-mind, to smooth over the jagged edges that made him thus? There was little hope of that. Beneath the stern comportment and commands, Maedhros’ mind was an impenetrable torrent of despair.

Maedhros’ gaze roamed the field, taking in the extent of their losses. The sunlight lent a false brightness to his dusky pallor; accentuated the scrawl of scarring on his cheek. A flicker of revulsion cramped his face. “Come,” he said, turning his back on the scene, “let us find a place apart.”

As they walked in the direction of the command tent, he said, "The ships from Balar have been sighted on the horizon. They are not equipped for warfare.”

That they would not have to fight another battle ought to have been a relief, but Maglor heard none in his brother’s voice and felt none himself. The lack of retaliation was its own quiet conquest. Shame could cut as deeply as any weapon.

“I guess that Ereinion and Círdan come to offer aid to their people," Maedhros continued. "A more appealing offer than the one we have made.”

Maglor looked over his shoulder, picking out unfamiliar figures among the ebb and flow of bodies. A grey-bearded man stooped over a sack of his belongings with an expression of dismay. A silver-haired elf with two ridged scars where her eyes had been was guided by another elf, shorter and with the slender form of one scarcely out of childhood. A woman clutched a babe to her chest, her lips moving in inaudible song.

Was Maglor right to have counselled his brother to fold these survivors into their numbers? Could they afford such a burden on the road? Was he only inviting resentment and discord into their midst, seeding future betrayals?

To persuade Maedhros, he had first spoken poetically of the power of mercy to move hearts to loyalty; then, with a mind honed for warfare, of the need for soldiers. The truth was he could not support the weight of Maedhros’ despair alone. “It disgusts me,” Maedhros had said, after Doriath, “that there are still those who look upon me with trust in their eyes.” Yet, without followers buttressing him Maedhros would collapse, and Maglor could not endure such a fall.

They could not afford to lose anyone to the succour of Ereinion.

“Then we must hasten our retreat,” said Maglor, as they drew up to the tent. A silent guard held open the flap.

Maedhros ducked inside. “We will. With so many wounded, I have decided to divide the retreat into two hosts. Those who cannot fight will travel with a guard south around Taur-im-Duinath and follow the Gelion north. The journey will be slower, but protected from any organised attack. Our best fighters will come with me and make as direct a retreat as possible by the same route we travelled along the Andram. I do not doubt that Morgoth will have tidings of these things soon, and he will know that Amon Ereb stands well-nigh defenceless. It must hold.”

Maedhros stopped beside the small folding table at the back of the tent. He splayed his fingertips over a map of the delta and pushed it across the desk’s surface. He did not look at Maglor as he said, “You will lead the second host.”

The air rushed from Maglor’s lungs as a breathless question: “What?”

“You are better suited to it than any others among us.”

“How so? What of Lisgon? These people are more likely to trust a dark elf—” Maedhros lifted his eyes only a moment to glare at him. “And you will need me on the Andram if your aim is stealth. Why then?” It was so quiet Maglor could hear his own blood rushing in his ears. “Nelyo,” he pleaded.

“Maglor. You forget that Lisgon was a thrall. They will trust him no more than they trust me. And yes, they will mistrust and despise you at first, no doubt. But you will make them love you. That is why. Now, do not make me explain myself further. You will take the second host.”

“There are other options—”

“Enough!” Maedhros shouted, then nervously glanced at the tent’s thin walls. His hand trembled. With lowered voice, he said, “You suffocate me, that is why. Your displays of remorse shame me.”

With this confession, all the defiance burning in Maglor’s breast turned to ash. How long? he thought. How long have you wished to be rid of me?

“As you command,” he muttered, and sank down onto an upturned crate. He let his head drop between his shoulders.

A moment later a triangle of sunlight sliced across the ground, shadowed down the middle, and the voice of Maedhros’ High Captain hailed them.

“Captain Lisgon. What is the news?” Maedhros said, steady, the heat of his voice contained.

“My lords,” the Captain nodded twice, acknowledging Maglor also, and stepped aside to reveal the man who accompanied him: a Green-elf, by his slight build and the lines like the veins of a leaf tattooed on his amber-brown cheeks and neck. One of few remaining who had long ago sworn fealty to Amrod and Amras.

“This is Orfion of Ossiriand,” said Lisgon. “He says that he was witness to— to the loss of the jewel, my lord.”

“Orfion," Maedhros said, as if greeting one with whom he was already acquainted. Likely he was: there were few of their followers whose names and faces Maedhros had not committed to memory. Then, forcefully, he said, "Speak."

Orfion recoiled as if struck by the command. He fell to his knees and prostrated himself. “I have betrayed my oath of fealty to your House, lord.”

Maedhros grunted, almost a laugh, and turned away. The elf tilted his face up, hands clutching at the fringes of the pelts covering the tent floor. His eyes locked onto the Maglor’s. Who could blame you? Maglor thought, watching the elf’s terror turn to confusion. Any fool would have broken an oath to the monsters Amrod and Amras had become.

“My brothers whom you served are dead,” Maedhros said slowly. “Unless you killed them yourself, I care not. Stand and speak, soldier. What happened on the cliffs?”

Orfion scrambled to his feet. Maedhros gestured to an unoccupied crate on which he could sit, and the elf accepted with noticeable relief.

“My lords,” Orfion said, “when Lord Amras was slain on the piers by… by those of your—our—own following, lord, myself and several others of his guard, not knowing where to turn in the confusion, and wanting to bring word to Lord Amrod, escaped the battle and came to where Lord Amrod and his men were guarding against flight by the western road. But Lord Amrod already knew of his brother’s fall, though not the manner, and his eyes were hollow as if his spirit too had fled, but when he heard me speak the words, that Lord Amras had fallen by the arrows of his own men, that his body had been thrown off the quay, then his whole face burned with a fey light. He passed through the stone gate, shouting and slashing—”

“What was he shouting?” Maedhros interrupted.

“My lord?”

“My brother, what was he shouting?”

“I do not know, lord. It was in your own tongue, of which I know little—”

“You served him for four centuries, Orfion. What was he saying?”

Orfion’s tongue flickered over his lips. “About the fire on the ships, lord. He cried Umbarto.”

Maedhros drew a long breath through his nose and closed his eyes. It was how Amrod’s madness always began, since Losgar.

“Carry on,” Maedhros said.

“My lord, he flung his sword about with such abandon, such hate, that I thought he might slay one of us, or himself. But it was thus stumbling into the night outside the city that he caught sight of a small group mounting the hills in the distance. Suddenly returned to himself, Lord Amrod commanded, ‘After them!’ We gave chase, but Lord Amrod ran so swiftly, as if driven by a fire within, and the men with us were weary and injured, so that all but myself fell behind. I was with him when he caught up to those we pursued, where the hills begin to rise and drop steeply into the sea, where you saw...”

Orfion paused, working his jaw around his next words.

“It was the Lady Elwing with her children and a woman-servant and their guard. I knew him for a warrior of Gondolin by his livery. He turned to engage us, but Lord Amrod paid him no mind. Swift as a hawk, he had snatched the children before the Lady or her servant were aware of him. And dropping to his knees and holding both terrified boys to his chest he held his sword to their throats.

“‘Hand over the Silmaril and they will live,’ he said. One of the children squirmed and a line of blood bloomed wet on his throat. There was no feint in Amrod’s voice. None dared to move or speak for a long moment. Then the servant spoke first, denying that her lady had the jewel with her. Lord Amrod laughed. ‘Of course you have it,’ he replied. ‘In that box you are clutching. Was it that very same in which you smuggled our birthright out of Doriath, where my brothers died in vain? Hand it over or I will slit your children’s throats.’ But Elwing had already silenced the other woman, and she drew the necklace out of the box. I thought she might hand it over, but she clasped it about her neck.

“Its light, my lord — I could scarcely breathe for the beauty of it, and the terror of the Lady wearing it. There were tears on her face that had been hidden by the darkness, and they now shone like little streams in the moonlight. I have never feared darkness before, my lord, but I did then. I fear I will evermore shun the night, having seen that light.”

Tears had gathered in Orfion’s eyes, and he sputtered to a halt. “Please forgive me, lords, I am not one prone to weeping, but the memory— it is impossible not to weep. I do not know why.”

“I do,” said Maglor. Compassion for the simple soldier who had become entangled in their doom warred with envy: it ought to have been him there, and Maedhros, looking upon the Silmaril’s light. Maglor would not have let it slip through his hands.

Orfion collected himself. “Even Lord Amrod was struck dumb,” he said, as if in answer to Maglor’s shameful thought, “and in his moment of faltering the children nearly escaped his grasp. Elwing lurched forward then, but he clutched them closer. He bared his teeth. ‘Hand it over!’ he commanded. She did not speak. She gazed long at her children, then touched the Silmaril on her breast, and for a moment I thought she would remove it. Then a fell cold light washed over the Lady’s face, and she spoke, quiet but hard, in the tongue of Men.

“And then she turned and raced to the cliff’s edge. She leapt, and as she fell she loosed a horrible cry. The light of the jewel glowed along the precipice — and then it was gone.

“All was a confusion of shouts and fighting. The woman-servant screamed her lady’s name and ran to the cliff’s edge. The guard commanded her to stop, and there was a struggle between them — I saw little of it, for Lord Amrod had risen to his feet and held again the edge of his sword to the throat of one of the children, who stood altogether still. The other wailed, and Lord Amrod drew his dagger and swung it at him. Rising and holding both blades aloft, he cursed them, saying that he would take them both with him. And then suddenly he dropped his weapons and crouched down before them and embraced them, and he murmured that he would save them, that he would spare them the burden— the burden of living.”

Orfion choked back the last words. “Then the guard leapt at Amrod, and dragged him to his feet — but as he did, Amrod drove his dagger deep into his thigh, and the man stumbled, and Amrod dropped the dagger and seized him by the neck. ‘I do not want to kill you, old friend,’ he spat. ‘Stand down, Galdor. This is not your fight.’ Then he threw the man to the ground. Amrod turned on the children again and then — my lord, I was certain he would slay them, and I could not bear it.

“I turned on him, my lords,” said Orfion, no more than a whisper. “He was not himself, I could see no other way. But I had no chance of overpowering him. He struck my face, he cut my hand and threw me away from him, away from the children. I could not see where I had fallen. But there was the clanging of swords, and I knew the one he called Galdor had risen to fight him. They fought fiercely, well-matched as they were, all the while Amrod shouting curses, wild ravings. Then he stopped. There was a long moment when I could only hear laboured breathing. Then gurgling. Still my sight was blurred, but I turned and saw the shape of Lord Amrod folded and broken on the ground. The cut to his throat had been deep — the pale dry grass was dark with his blood.”

Orfion wept freely now. Maglor ached to weep with him but the well of his tears had run dry. They had known Amrod and Amras had died — one always felt the death of a brother, and that rending of the soul was even more potent, Maglor had now learned five times over, when one was doubly bound to his kin by oath. Amras died early in the night, at the hands of their own followers. They had not known the manner of Amrod’s death until now.

“I had loved him,” Orfion said, “him and Lord Amras. I saw them both fall, and Lord Amrod because I had failed to protect him, because I had set upon him myself. I betrayed him.”

There was a silence. Lisgon was staring at the ground, knuckles white around his sword hilt. A grey tint had settled over Maedhros’ face. The camp noises seemed far off.

Outside the tent walls, the sun was bright and the birds twittered in mockery.

“You served him well, Orfion,” said Maedhros.

Orfion looked at him in surprise. “My lord?”

“You ensured he did not die a monster.”

Maglor looked at the ground. He could not let Maedhros see his doubt. It is what Maedhros needed to believe.

The tale-spinners had made Celegorm the villain of Doriath’s fall, and the rest of them had looked the other way as their dead brother was censured for the devastation they all had wrought. It was convenient. It was politic.

But when their youngest brothers had clamoured for blood and vengeance, and would have pursued it whether Maedhros stood with them or not, Maedhros still saw his little brothers who had done no wrong. So it was Maedhros who signed his name to their threats of violence, and Maedhros who stood at the forefront of the troops and gave the command to set fire to the perimeter and seize the boats. Maedhros who struck the first blow.

For all Maedhros’ efforts to preserve the twins’ innocence, Amrod and Amras died the villains of Sirion.

Though it cramped his heart with shame, Maglor could not bring himself to regret it. Not if it meant there was hope of forgiveness for his last living brother.

“And the children?” said Maedhros. His features brittled, fault lines slipping under the weight of memory. “Do they live?”

Of course, the children. Maglor’s shame sank deeper for the pair of twins who had escaped his thoughts altogether.

“I do not know, my lord,” Orfion said. “After the struggle between the two lords, they were gone, and the woman-servant too. The lord Galdor cried out for them, but there was no answer. He looked at me: ‘Do not follow me and I will not kill you,’ he said. Then he ran off, calling their names: ‘Gwereth! Elrond! Elros!’”

Orfion heaved a breath and looked between Maedhros and Maglor. “Thus I was able to come to you, my lords.”

“Thank you, Orfion, for your honest report. With the death of my brothers, I deem you released from your service to my House. You are free to go where you will.”

Orfion’s hands cupped his knees. “My lord, I have nowhere to go in these parts.”

Maedhros hummed in the back of his throat. “I have given all survivors of our own host and of these Havens the choice to join us in retreating East. A Silmaril is lost to the depths of the sea. Our oath binds us now to stand against Morgoth, no matter the odds. You are free to travel with us, if you wish. My brother’s host has need of guards, if you consider yourself fit for such a duty.”

Rising from the crate, Orfion said, “Lord Maedhros, Lord Maglor,” he bent twice into an awkward bow, “thank you for your mercy. I am honoured to continue to serve you in the war against the Enemy.”

Maedhros nodded. “Convene here before midday. You may leave us now.”

A taut silence followed. The names of orphaned princes hung heavily in the air: Elrond, Elros. Eluréd, Elurín.

The symmetry would make a fitting second canto to the tale of Dior’s sons that Maglor had sent singing down the rivers and through the wilds of Beleriand. How Maedhros repenting had run crying through the woods, seeking the two helpless boys; how dead Celegorm’s vengeful soldiers carried them off; how Maedhros had been in anguish when the search was given up.

All of it was true. (Save the birds: even Maglor was not so drunk on hope as to dream up a miraculous rescue by creatures of the forest. That had been the bards of west Beleriand.) The remaining sons of Fëanor had indeed grieved when they discovered the bodies of two boys frozen in the folds of an oak: they had grieved the Silmaril slipping even further from their grasp. But when none dared speak the ugly truth swaddled in a blanket of regret and repentance, omission was easy.

They were never meant to die. The blood of Lúthien had eluded them so well that death had found them before they could be made currency in the war. It had been Celegorm’s design, but they had all known. Later, when Maglor had sought to dam the flood of his brother’s guilt, Maedhros had snapped: “Make no more apologies for me! Never again will I be persuaded to employ the tactics of our Foe. We do not barter with children.”

Yet they had assailed Sirion with fire. Was that not a weapon of the Enemy?

At last Maedhros spoke, his voice heavy as if the words were dredged from a deep well of thought. “Maglor, you will return to the city and search for Elwing’s sons. Tell no one what you are doing. Ensure they are safe and unharmed.”

Maglor rose, smoothing from the edges of his mind the memory of those other children. Here was a chance for a different story.

“Yes, my lord.”

He ventured stepping closer. Close enough that he had to tilt his chin up to meet Maedhros’ eyes, close enough that he might have laid a hand on his arm, felt his pulse, felt the fear his cloaked eyes concealed. He did not.

“Maitimo,” he said. “I will find them.”

Chapter End Notes

Thank you to firstamazon and Tethys_resort for offering feedback and encouragement on this chapter. Thanks to Chestnut_pod's brilliant Elvish Name List for the names Orfion and Lisgon. Dornil and Gwereth were devised by me and I take responsibility for any misuse of language -- I like the sounds.

Taken Captive

The aftermath of the flight from the cliffs.

Read Taken Captive

“Elros! Please stop struggling!”

The child writhed and shouted and beat his fists against Gwereth’s chest. She fumbled with the latch on the cellar door, squinting and blinking furiously. It was no use: the fog came from within, from the panic that drove her stumbling through the wilds about Sirion, dragging the children behind her. Galdor had caught up to them, but not long after his wounds proved too severe for him to carry on. “Go,” he had urged her; “Go — if I am fated to live, I will recover. If not, I count this a noble end. You must find a place to hide.”

So she had fled to her friend Embor’s home on the outskirts of town, where most of those warriors of the East who had not been deceived and enslaved by the Enemy dwelt. She had not known where else to run, and she had hoped that under the protection of a warrior of Bor’s folk, burdened by age though he was, she and the children might yet survive. They might wait out the retreat of the sons of Fëanor. And perhaps — perhaps help would come before Morgoth sent his legions against them, a ruined city, defenceless without the Silmaril to preserve them.

Gwereth was relieved to find Embor’s home intact; but he was not there. There was no time to wonder or to mourn what had become of him.

Elros’ fist struck her ear as she bent to open the sloped hatch and a jolt of pain shot through her skull.

“Blood and darkness, child!” she snapped. “Stop hurting me! I am trying to help you!”

Her sharp tone silenced him and her heart cramped with regret. How could she blame him, a child of six who had lately seen his mother leap to her death, whose own life had been threatened, who had seen horrors beyond— Well, Gwereth had been nearly their age when she had watched the blood spilling from her father’s skull on the flight from Brethil, and the image haunted her still.

“Oh, I’m sorry,” she said, cupping the back of his head and holding him closer. “I’m sorry, Elros, I know—”

He loosed a piercing wail.

Flinging the hatch open, Gwereth yanked Elrond after them down the short flight of steps. The door banged shut, smothering the room in sudden darkness but for a thin square of light around the doorframe. Gwereth fumbled for the striker to light an oil lamp that stood by the entrance. It leapt to life, and she inhaled sharply at the reminder of the ravaging flames that had blazed through the night, eating through the wood and thatch of Sirion.

She grabbed an iron rod to bar the door, then reconsidered: surely anyone finding a cellar locked from inside would suspect. A single bar would do nothing to hold off these warriors if one were determined to break in. Better to leave it, and trust to the barrels and crates and shadows to conceal them.

She tucked the rod into her belt instead. It was not much, but she was descended of both Haleth’s and Emeldir’s people, whose traditions the elders of Sirion had preserved. She knew how to fight. A bar of iron would serve as a weapon in utmost need.

Elros squirmed free and ran to the opposite end of the room where the ceiling sloped down steeply, scarcely high enough for a child to stand. He pounded his fists against the wall. “I hate you! I hate you, Gwereth!” he screamed. “We have to go back to Mama, we have to!”

Gwereth summoned all her strength to resist the urge to comfort him. Elrond, shivering and silent beside her, needed her no less.

“Elrond, my love.” She knelt before him. Blood crusted along the shallow cut on his throat and she licked her thumb to wipe some of it away. It struck her how small and fragile he was. Her own small hand covered half the girth of his neck. She held his narrow shoulders and tried to meet his eyes.

“Tell me how you are, sweet one.”

His gaze dropped to the floor, but his lips moved silently.

“I cannot hear you, love,” said Gwereth. “What is it?”

After struggling again to speak, he gestured at his trousers, and was seized by silent sobs. At the other end of the cellar, Elros fell quiet.

Gwereth patted Elrond’s trousers and found them warm and damp. He had wet himself.

“Oh, Elrond, it’s all right,” she reassured him. “It happens sometimes when we are scared. Are you scared?”

Elrond nodded. Gwereth glanced around the cellar for something she could use to clean him off. A rag covering a large storage jar would have to do.

“Elros,” she said, looking at him and then nodding in the direction of the jar, “can you fetch that rag for your brother?”

He hurried to obey, subdued by his brother’s distress.

Gwereth rubbed her hands up and down Elrond’s arms. “Can you help me take these trousers off, dear?” Elrond nodded again but did nothing, so Gwereth unlaced and shimmied them down his thighs. She guided his feet out of the soiled clothing.

Elros wandered over with the rag and stared at his brother. “It’s all right, Elrond,” he said, “it happens when you are scared.”

“That’s right,” said Gwereth.

There was no water, so Gwereth spit on the cloth and wiped him down as best she could. She removed her own headscarf and tied it into a skirt around his waist. The trousers she hung to dry on the low rafters.

“Why do we have to be here?” Elros asked. “I want to go back for Mama.”

There was a cry bubbling up inside him and Gwereth set a reassuring hand on his back. He nuzzled himself into the hollow between her chest and arm.

In the moment of quiet, she let her eyes fall shut. But plastered on the backs of her lids was a vision of her lady leaping to her death. Gwereth drew a shaky breath. Her imagination supplied the aftermath: Elwing’s graceful form beaten against the rocks, broken, and dragged out to the unknowable depths of the sea. Their lady, their Silmaril, their protection against the darkness: all gone.

Elwing had despaired.

Anguish swooped through Gwereth’s stomach. She felt as though she were toppling forward. Her eyes snapped open. Elrond stared back at her, dark brows pinched over the bridge of his nose.

She was crying. “All is well,” she said, scrubbing the tears from her cheeks.

The wells of Elrond’s silver eyes swelled and he sucked his lower lip between his teeth. He knew she was lying; of course he knew.

“Aaghh!” The yell exploded beside her, and Elros jerked free of her hold. “We have to go back!” He bolted for the door, clambering up the steps and banging his little body against it.

“We can’t,” Gwereth said, too meekly for Elros to hear through his shouting. “Elros!” she cried. “Please, you must be quiet! People are looking for us, people who want to hurt you.”

“But Galdor killed the angry elf,” he said, slamming the flats of his hands on the door and drumming his feet on the steps. “Why, why would they hurt us? We didn’t do anything bad! Aaghh!” he wailed again. “We need to go back for Mamaaa!”

His next shout ripped through Gwereth’s heart. He banged his head against the door sill, hard enough to send him toppling backwards off the steps and crashing to the floor. The back of his head thudded horribly as it hit the uneven stones. He fell silent.

Gwereth screamed and launched to his side, landing hard on her wrists. There was a terrible moment when she saw him still, eyes closed, and imagined him dead. Her breath stopped. But then his eyes blinked open, he rolled his head to the side, and her relief was so intense her arms buckled beneath her.

She fell to her elbows and cupped his face. “Oh, Elros, Elros, Elros! Elros can you hear me?”

He blinked again, stunned; stunned but alive. She stooped over him, spreading her body over him like a swan tucking her fledgling beneath her wing.

“Is he alive?” Elrond asked, squatting beside them.

“Yes, yes, he will be all right,” she reassured him. “Come, Elrond, come. We need to keep out of sight.”

She bundled Elros to her breast and shuffled on her knees towards the other end of the room, beckoning Elrond to follow.

“I’m hungry,” said Elrond.

“Ssh, ssh,” Gwereth said. “We will find you something to eat.”

As Gwereth cast her eyes about for something to fill his stomach, a voice came from the other side of the door. Gwereth froze.

“There are children here, lord.” It was a woman’s voice, speaking low but in a rush, as if agitated.

Elven-light footsteps crossed the boards above them. Elros groaned in Gwereth’s arms.

The steps stopped. “How do you know?” said another voice, deeper and steadier than the first.

“I heard them,” the woman answered curtly.

In a rush of panic, Gwereth tucked Elros, still half-limp and stunned, into an empty crate. “Elrond,” she whispered, “you need to get inside with your brother. Hide.”

He looked at her warily but did not struggle when she helped him in. He sat cross-legged, squeezed tightly in the corner, and stared at her with sorrowful eyes.

“I love you,” she said. “You’ll have to duck, sweetling. Please be quiet.”

He curled forward over the body of his brother and Gwereth pulled a cloth over the crate. Then she drew the iron rod from her belt and turned towards the door. The riot of fear inside her cooled and hardened.

The door swung open. The light of the rising sun spilled into the room, blindingly bright. Against it were silhouetted two pairs of long legs, booted in dark leather. One crouched in the opening with an arm braced on the lintel.

“Do not go in,” the woman’s voice cautioned. “You do not know who else is with them.”

“Hold your peace, Dornil,” said the man. “Wait here.”

The elf-man was tall enough to have no need of the steps, dropping down in one fluid motion and landing lightly despite his long mail shirt. His red tabard was embroidered across the breast with a silver star: the symbol of beauty and hope for Elf-kind that these soldiers had turned to a sign of fear, its eight keen points and eight piercing rays bringing to mind not a bright star of heaven but a bludgeon spiked and barbed.

Even at the higher end of the room he was too tall to stand upright, and as he approached he dropped to his knees.

Gwereth lifted the rod and lunged from the shadows. She swung.

At once a large hand, gloved in leather, was around her wrist. There was no pain: the only discomfort came from her own resistance to the warrior’s hold, and she knew then that he wielded but a fraction of his strength against her. No amount of friendly sparring had prepared Gwereth for such a foe. She felt diminished, shrunken, as Beren must have in the pits of Gorthaur, or drowsing beneath the throne of Bauglir. And Gwereth had neither Elf prince or princess to defend her, nor any great doom to protect her; and the foe she faced was, she deemed, himself a prince of Felagund’s power — and none of his virtue.

She gasped and staggered to a halt. The elf let her go.

“I have not come to hurt you,” he said. “The battle is ended.”

His voice was unlike any she had heard before. It was the clear chime of bells running together as a stream leaps over stone; but beneath this, it was the deep rumble of the sea, impenetrably dark. It was a sound so arresting she had to strain to hear the words running through it.

Sound gave way to sight as her eyes adjusted to the light. The elf wore no helm, and his dark hair was held close to his scalp by many rows of braids pulled together at the nape of his neck. Shorter curls had come loose around his face, softening the edges of his sharp elven features; his skin shone like wet clay in the lamplight. Heavy brows settled above deep eyes of the sort whose colour shifted and danced. Gwereth had always imagined it was because the Treelight that flickered within them eluded the untrained eye, ever skipping from hue to hue but never settling. It had been so with the Silmaril, too.

It was strange to see that light in the eyes of an enemy.

He said, “Have you heard the message, lady?”

Gwereth shook her head, transfixed. Dread closed in around her, groping; her limbs hung uselessly, numbly, as if severed from her body.

“The sons of Fëanor are withdrawing. All those who wish are free to follow: I urge you to consider it. The Havens will not be safe for long.”

The hold with which his arrival had seized her slackened. Her mind began to clear. “What of the Lords of Balar?” she asked. Ereinion had not been Gwereth’s king, nor Círdan her lord, but they had ever been kind to her lady. Surely they would come to their aid.

The elf was silent, his jaw stern for a long while before he answered. “I do not know.”

Gwereth wondered at his pause. She wished this elf was not her only source of news from without.

“We have also come to tend the injured,” he said. “Are you well, lady?”

He reached for her. Gwereth flinched.

“Yes. Yes, I received no hurts,” she said.

“Are there others with you?” the elf asked. His tone was gentle, but knowing, and his look stern. Of course: even had his servant not heard them, he was Elf-kind: he felt the children’s presence.

She lied all the same. “No. Only myself.”

His continued silence pressed into the corners of the room and Gwereth’s body awoke at last from its stupor. Like a frightened creature who, without hope, turns and faces its pursuer, she cried, “Leave! Leave, there is nothing here!”

But her pleas glanced off him like sticks hurled at the sturdy bole of an oak. It was as if she had not spoken at all.

“You have children with you.” It was the voice of the elf-woman in the open doorway. “Show them to us.”

“Dornil,” the other elf said firmly, keeping his eyes on Gwereth. “If you interfere once more with my errand, you will be sent to the camp to load the wagons.”

The elf-woman shrank back, a beam of light catching her pale features and revealing a flicker of hurt, as if she had not expected so harsh a reprimand, and for a moment Gwereth’s heart clenched in sympathy for the servant of so terrible a lord. No — it was not so. She was as much a part of their campaign of violence as he.

At that moment, a whimper squeaked from the shadows. The elf-lord’s eyes were drawn to it. No. Gwereth dropped to her knees, folding over and cradling her face in her hands.

“Please do not hurt them,” she begged.

“Lady,” the elf said, “I have already assured you: we mean you no harm.” He paused. “Are they wounded?”

Gwereth choked out an affirmative sob. Some desperate instinct drove her to tell the truth. “Yes. One of them. He fell. He hit his head.” She sobbed again, ashamed to confess to this failure of her care.

She did not stop the elf-lord as he made his way on folded knees towards the source of the whimper. Raising her head, Gwereth watched him lift the cloth from over the crate. Elrond sat upright, hesitant but rapt at the stranger before him.

It was so incongruous, the tenderness with which the elf cupped Elros’ head as he drew him out. He lay him down to rest against his thigh while he removed his gloves and metal bracers. He adjusted Elros’ body carefully, as Gwereth in her panic had not. The scene brought to mind a wolf Gwereth had once encountered, tending her injured cub.

All his attention was turned towards the child. Briefly, the thought entered Gwereth’s mind that now again she might strike him; but the heat of her anger had withered. She did not know if she could have found the strength to lift her weapon.

The elf’s large hands nearly encompassed Elros’ head. He breathed deliberately and slowly, watching the child.

“The hit has disturbed his brain—” he paused, as if listening, and sank his fingers into Elros’ hair at the base of his skull; “and caused a small fracture in the bone.”

Gwereth was surprised to hear herself ask, “Can you heal him?”

“Yes, I think so,” the elf said. “But this child— is he mortal or elven?”

“Mortal,” Gwereth said in a rush. “He is Mannish.”

The elf looked through her. “I think, lady, that you do not tell me the whole truth. But neither of us has been forthcoming with the other.” He scooped Elros to his breast and shifted to face her fully. “I am Maglor. Son of Fëanor.”

The revelation did not startle her as much as it ought have. In her heart she had known from the moment she heard him speak. She had encountered few in her life whose presence carried such power. Her lady had been one, as had Eärendil and his mother, ere she departed. But theirs had not been marred by evil deeds.

“I know that you suffered great hurt at the hands of my brother,” he said, “and you have reason to distrust me—”

A broken laugh leapt from Gwereth’s throat, and with it a daring defiance. “Distrust? I have reason to hate you. I have reason to kill you. Do not tell me that you are guiltless, Maglor son of Fëanor.”

“I am not—”

“Did you not lead an assault on a haven of refugees?”

“Lady, let me speak,” he said sharply.

“Why?” Gwereth said. “Why should I let you speak?”

He made no answer. Elros blinked in his arms, his head lolling to the side to face her.

“Gwereth?” he said weakly.

Then the muscles around his mouth quivered. He retched, vomit spilling onto Maglor’s thigh.

Gwereth leapt towards him. Her fingers brushed Elros’ body; then she was herself jerked backwards.

“Do not,” the elf-woman’s voice hissed in her ear, “lay hands on my lord.”

This time Maglor did not reprimand her. He was cleaning the vomit from Elros’ face with the hem of his tunic. Then he took a water skin from his belt and wet Elros’ lips, and Elros gulped greedily from the bottle’s mouth. He gasped, reviving, as it was removed.

Maglor left the sick sticking to his own garments. One more stain among many.

Only when Elros was settled did Maglor set eyes on his servant, who still held Gwereth by the arm. His gaze was penetrating, warning. The silence lengthened, and Gwereth suspected they took counsel mind-to-mind.

The breaking of the connection was palpable. Seemingly with her lord’s approval, the elf-woman tied a slender rope around Gwereth’s wrists. Her touch was firm but painless. Gwereth did not struggle.

Clarion trumpets sounded outside, a simple progression for lifting up the heart. A summoning.

Maglor scooped up Elrond with his other arm, balancing each child as if he weighed no more than a basket of herbs. Perhaps they followed Gwereth’s cue or perhaps their fear was blunted by some wizardry, but they made no effort to resist. Elrond’s fist even bunched at the collar of Maglor’s shirt, clinging to the strong, solid body.

If Gwereth had not known otherwise, she would have thought she looked upon a saviour and not a sacker of cities. But a killer he was, and a thief of children. For had he not spoken to his servant of an errand? What other could it be than to take them captive?

At least he would not kill them, as his younger brother would have done. That much she trusted, though she knew not why.

Forgive me, my lady, she beseeched Elwing, whose spirit had fled to a fate Gwereth could not know. But she prayed still because she allowed herself to hope: that Elwing was not gone beyond the Circles of the World; that she might see her children again, in some far removed time long after Gwereth and all the proud people of Haleth had faded from memory altogether.

I will protect them, she promised. With my life, I will protect them, and if by any power in me I can deliver them from their cruel captors, I swear to you, lady, dear friend: I will.

The last words she muttered softly in the tongue of her people.

Her keeper nudged her forward. “I am Dornil,” she said. “Come, Gwereth, nurse of the sons of Eärendil. For that is your name and station, is it not?” Gwereth bowed her head. “Do you accept the continuance of your charge to care for these children under the command of Lord Maglor?”

Gwereth nodded.

“Good. I will lead you to our camp. It will be better if you do not struggle.”

She guided Gwereth out the open hatch. Maglor and the children followed behind where she could not see them.

On her flight from the cliffs Gwereth had not had time to take in the sight of ruined Sirion. Now she saw neighbours, known and unknown, drifting among the wreckage: searching for possessions of their own, perhaps, or unclaimed goods that could be salvaged. If any had been slain in this quarter, their bodies had been cleared.

A cloak was cast over Gwereth’s shoulders. Dornil was not as tall as her lord, but she was taller than Gwereth by far, and under her cloak Gwereth all but disappeared. If she had friends among the lingering folk, they would not mark her. She and Dornil approached a mighty warhorse, and Gwereth was slipped free of her bonds and helped into the saddle. Dornil mounted ahead of her, forcing Gwereth to take hold of her waist to keep steady on the horse.

As they turned, Gwereth twisted towards the mouth of the river and the Isle of Balar; but they were far from the bay and the reeds grew too tall between them. If help was coming to the people of Sirion, Gwereth would likely never know.

Chapter End Notes

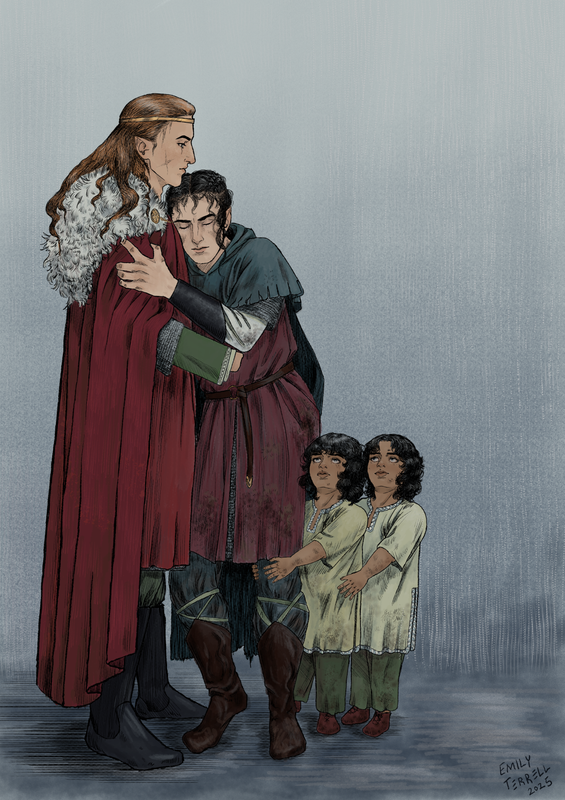

It's not exactly reproduced of course, but definitely had this stunning image of Maglor and Elrond and Elros by anattmar in mind writing the end of this chapter. Thank you to cuarthol for beta'ing this chapter.

They Alone Remained Thereafter

Elrond, Elros, and Gwereth are brought back to the Fëanorian camp. Maglor explains his decision to Maedhros.

Read They Alone Remained Thereafter

There were not many horses in Sirion. Elrond’s mother’s people were not horsemen, and his father loved ships. Elrond had been on a horse only once before, in the wildflower fields with Gwereth’s friend Embor. It had frightened him, and Embor had lifted Elrond to the ground with his strong hands, laughing kindly. They had been hiding in Embor’s house, he and Elros and Gwereth, when the elf-warriors came. Elrond could not remember seeing the horse in the stable.

The bounce and sway of the animal beneath him was uncomfortable. His legs ached, like when he had once caught fever. He and Elros were snug between the horse’s neck and the elf-warrior’s large torso: Would he let them fall if Elrond let go? He glanced down at the road — a narrow dirt path, not yet the wide cobbled streets closer to town. It was far to fall, and Elros was already hurt. And where would they go? Mother was gone, Father was gone, Galdor was gone.

Gwereth was coming with them. Gwereth would keep them safe.

Elros nodded and whimpered behind him and Elrond clung tighter, fists bunching in the horse’s mane.

Low stone roofs peeked above the reeds. They were approaching the river crossing to the quay and the centre of the town where Elrond and Elros and his mother lived — and his father, when he was not at sea. No: Mama was gone, Elrond remembered, and his throat felt tight like he had taken too big a bite. Elros had wanted to go back for Mama and Elrond did not know how to explain to his brother that she was gone. But he knew. The Silmaril was gone, too. They were not safe in Sirion anymore.

All his life Elrond had learned to fear orcs and wolves and dragons. He had only seen these monsters in paintings and wood carvings and the pictures the elf-singers painted in his mind. At first, when the warrior-elves attacked them, he had thought they were orcs, and he did not understand. How could it be? They had the Silmaril. They were safe. “No, my loves,” his mother had said when Elrond asked, “they are not the Enemy’s servants — they are his enemies, as we are, though they serve his purposes. They are elves. Fallen elves who have malice in their hearts, but elves all the same.”

Why would enemies of their Enemy make war upon them?

Elrond remembered times when his mother’s friends and counsellors let slip words in their presence about evil elves who had destroyed her home; but Mother had always shushed them, so Elrond assumed they were harmful lies. Mother fought lies. She brought the people together.

But then an elf had wanted to kill him and Elros. A terrible, fell, and beautiful elf with bright eyes like Galdor who had accused his mother of stealing a birthright from him. Mother would never steal. But then, Elrond never would have believed that Mother would run away to die without them, and she had. She had said: “Please forgive me, my loves. I do not think my doom as high as Lúthien’s, but this course alone remains to me.”

None of it made sense.

Elrond sniffed. The sky smelled burnt. Elrond had smelled cookfires before, and burned bread. He had never smelled a burned sky. It stung his eyes like when the wind off the sea blew hot smoke from a firepit in his face.

This was nothing like that, though. In the night the wind had howled and the flames had roared back, but now it was still, and even though the sun was warm Elrond was cold in nothing but his tunic and the rag Gwereth had tied around his waist. He hoped they had a new pair of trousers for him wherever they were going.

He must have shivered, because the elf-warrior’s arms narrowed and brushed Elrond’s shoulders. He shrank into himself so they would not touch. His chest tightened remembering the strong and armoured arms of the other elf-warrior, the one on the cliff, squeezing the air from his lungs.

They continued down the road and the burnt smell turned sour. Rotten. A smell so thick he could taste it and his belly bubbled in protest. He scrunched his face and water seeped from his eyes. The rotting air settled deep in his lungs and spittle forced itself through his pinched lips, and he knew if he did not release the horror coiled inside him he would be sick: he let out a sharp long wail. The elf-warrior’s body curled closer in answer, pressing in around him. It was not what he wanted at all. Elrond shrank even smaller and covered his face with the collar of his shirt.

“I remember the first time I smelled a burning body,” someone said. It was the voice of the elf-woman, the one who had taken Gwereth on her horse. Good: she was still with them. “I was of course not so young. Alas that the Doomsman’s words have brought this horror even upon children.”

The elf-warrior hummed low, like a growl caught in his throat, and said nothing.

Burning bodies. Could she mean the horrible thick rot in the air was bodies? Why were they burning bodies? The dead ought to be buried at sea. That was how they had always done it, when age or sickness or injury snuffed out a life.

Elrond swallowed, dry and bitter, and wiped the dribble from his chin with his shirt. He was messy: messy with blood and urine and spit. He thought of the sea where the dead were buried. He wanted to wash away all of this filth in the sea and never come up.

Maybe he would find his mother and the Silmaril there.

The smell worsened the closer they came to the bridge. Somehow, Elrond grew accustomed to it. He supposed you could grow accustomed to anything if you had to endure it long enough.

As they crossed the bridge, Elrond saw them at last: bodies, a great mound of them heaped on the stone quay. Or so he guessed, for it was hazy and shapes amid the heap were difficult to make out. It looked more to Elrond like the wet sand he would let drip from his fist on the beach. Drip drip drip until a wormy grey hill formed beneath his hand. Several biers ringed the great pyre. Elrond wondered who they were, and why they had deserved this special treatment when the others had not.

For the first time since they had left Embor’s house, the elf-warrior spoke. Not to them: Elrond could tell because his tone and pattern was that of adults speaking to each other. He had a clear deep voice. Its harmonious lilt was all wrong. It should be rough and sharp, like the other warrior’s; like the smoky stinging sky. Despite the clarity of his speech Elrond found him difficult to understand, as if his ears were full of water.

He was asking the woman something about his brother’s body.

“He was not recovered from the river,” she replied.

“I did not think the river so deep here.”

“No, my lord, not too deep — but when they dove to search for them the bodies had all been swept to sea. Lord Ulmo has claimed them, it seems.”

“Lord Ulmo has claimed many things this night.” He was silent another moment. “And Amrod: You said you did not find him?”

“Nay, lord. Perhaps another came to him before I did. He was gone.”

A long and heavy puff of breath brushed the back of Elrond’s head. “So be it,” the warrior said. “May their souls rest and may Ilúvatar’s pity find them.” Then, so quiet Elrond was sure he did not intend to be heard, he added, “Though my heart tells me it will not be so.”

The elf moved the reins into one hand and closed the other arm around Elrond and his brother. Elrond had already made himself as small as he could, so he sucked his breath in and held it. He felt his eyes bulge and his neck tighten. The breath escaped and he gasped, lungs pushing against the large hand that covered most of his side. The hand did not resist the expansion of his chest. He breathed again, slowly this time, and the hand rose and fell with the rhythm of it.

It reminded Elrond of the weight of a thick winter coverlet, and he fell into a heavy slumber.

The few tents that had made up their bivouac had been disassembled by the time Maglor returned to the camp with the children and Dornil and their nurse. Wagons had been loaded with both goods and people and yoked to the horses. They lined the road that had been a footpath through the tall grasses when they found it, and was now trammelled wide by the passage of their army. This host would be Maglor’s charge on the long southern route to Amon Ereb. Uncharted lands: he wondered how many, how much, they would leave behind or lose along the way.

The sun blazed directly above them: the treeless field was hot. Sweat dripped down Maglor’s chest beneath layers of linen and mail and wool.

What remained of their army stood in loose formation at the eastern end of the field. Seeing them thus assembled was like looking upon a field of rye after an errant river had swept through half the crops, leaving behind a stark scar of barren mud. How many of those missing had been casualties? How many had been deserters?

The commoners clustered about their ranks came nowhere near to making up the numbers of their losses. They were perhaps half again the size of the army, many of them elderly, crippled, children. Desperate people who believed death to be their only other choice.

All heads faced the two men standing on a wagon before them: Maedhros addressing them, so capably playing the battle commander even in his despair, and Lisgon beside him. Maedhros’ voice carried to where Maglor and Dornil sat upon their horses, watching.

“Those are your words,” Dornil said.

“In some measure,” Maglor replied. Maedhros’ speech was his own, but laced with Maglor’s words from that morning, reordered into plainer but no less subtle language. It was a skill Maglor, who had no talent for simplicity, had envied at times.

“So it was your counsel to offer mercy and bring this remnant of Sirion with us?” Dornil asked.

Maglor was too weary to rebuke her for her prying. And why should she not know? “Yes. And it is I who will lead them — and you will come with me, commander.”

Dornil exhaled, and Maglor knew another question lagged behind.

“What of these captives?” she said, gesturing to the children and their nurse. “Was it Lord Maedhros’ command to take them? Or was that your own counsel also?”

Maglor saw no need to answer, knowing Dornil had reached the correct conclusion even before asking. Ever did she see through him, even as her husband had.

When he was a child, Maglor had gathered fledglings fallen from their nests. He had set them in a basket and swaddled them in blankets and fed them from his own hand. “Children ought to be reared by their parents,” Fëanor would scold him (speaking also, Maglor later realised, of himself). “You should leave them be. It is not your role to meddle in the fates of Yavanna’s creatures.”

But Maglor had continued to nurse his fledglings for many years, hiding them away where his father could not find them. He never was able to teach them to fly, though often they discovered this ability on their own. Those who did not became dependent upon him for the remainder of their lives — and he on them. It was this realisation that had made him stop.

That is until he had set eyes upon Elwing’s orphaned sons and his heart had cried Help them.

It was this he would shortly have to explain to his brother, who had finished speaking and now wove through the crowd towards them.

He made a sign for Dornil to dismount and aid him in doing the same. Doubt swooped through his stomach. He stamped it down. He prepared to defend his choice.

Lifting Elros then Elrond down from the horse, he said to Dornil: “They are not captives.”

“You did not follow my command,” Maedhros said.

They were alone, save Lisgon who stood by as ever, a silent sentinel of support beside his lord. The boys and their nurse had been settled in a carriage with several other children and their guardians, and remained under Dornil’s watch. A healer had been summoned to attend to Elros’ injury.

“You commanded that I ensure they were safe,” said Maglor. “I judged that they would be safest with us.”

Maedhros huffed and his eyes darted about, landing on his hand. He curled and uncurled his fingers, as if testing their dexterity. Or preparing to strike. The hand instead came to rest on the hilt of a dagger at his left hip.

“And Dornil?” he said. “Did I not command you to tell no one of your errand?”

“You did. But I came upon her on my way, returning from her search for Amrod, and I trusted her to aid me. She is my chief commander.”

Maglor glanced at Lisgon, whose eyes were veiled and cast upon the ground.

“You should not trust her,” Maedhros said. “She is vengeful.”

“Nonetheless,” Maglor said, “she is loyal, and we have few such people left to us.”

“Tell me then: was it Dornil advised you to take Elwing’s children captive?”

Maglor knew if he paused too long that Maedhros would suspect, so he offered a half-truth.

“No,” he said. “I brought them here because they were hurt and needed healing.”

“You could not have healed them there?”

Leave them be, Fëanor had said. Ensure they are safe and unharmed, Maedhros had said, and they had been. Safe enough. He had felt the fierce fire of elven blood in Elros’ spirit, had known the boy would heal on his own. He might have left them there, in the care of the closest person to a mother they had left, and his brother’s command would have been fulfilled. He might have brought back the welcome news that the children lived and they two might have carried on spinning and spinning in ever tighter circles until they were all that was left.

Maglor had done otherwise. The weight of that decision hung on him like the cloak of kingship that had once been fastened across his shoulders, outsized and heavy. He had learned to bear that mantle; he would learn to bear this one, too.

“Healed them, perhaps,” he said in answer to Maedhros’ question. “And left them to an unknown fate. They need protection.”

The skin around Maedhros’ eyes twitched as if rebelling against the firm set of his lips; as if trying to smile, held back by the same stretched thread that held him back from madness.

His next words were in the language of their birth. “You believe yourself the best-suited to that task, then?” So swiftly as to be almost imperceptible, Maglor sensed Maedhros skirting the boundaries of his mind. “I thought you had given up nursing fledglings long ago, brother.”

Maglor refused to permit the intrusion. “It will not be my task,” he said. “Their nurse is with us. Their father’s return is doubtful, they have lost their mother, the nurse is the closest thing left to them—”

“Lost their mother?” Maedhros interrupted. “Tell me, how did that happen?”

“She chose to die!” Maglor cried. “She left them.”

“You think yourself guiltless then?”

“We came because our brothers would have gone without us—”

“Did you command soldiers in the sack of this Haven or not? Did your sword, your voice, not send dozens of souls to Mandos?” He did not await an answer. “We made war on these people because of our oath, Macalaurë. Not because of our brothers. No more than we sacked Lestanórë because of Tyelkormo. Do not forget that, when you write the lament of this battle.”

That last was designed to hurt, but Maglor found himself too rapt in contemplation of his brother’s tone and manner to feel it. There was no heat to his argumentation, no real condemnation. It was not what Maglor had readied himself for at all.

When Dior’s sons had been lost, Maedhros’ face had contorted with grief and rage. He had wailed and torn his hair, as he had not done since the slow trickle of rumour had reached the wilds of Ossiriand and put an end to the mute endurance of his disgrace, singing the death knell of his last hopes: that Hithlum was overrun and the High King killed.

That was the sort of raw despair Maglor had thought would surface now. He had thought he had seen it sparking in the lines of Maedhros’ face before he set out to find the children; but if he had (and he doubted it now), it had been snuffed out. For all that the tragedy of the previous night had shredded his own heart to ribbons, Maedhros was as cold and politic about the outcome of this battle as he had been about its preparations.

Maglor understood what he must do. It was not sentiment that would earn back his brother’s trust, but reason. Maglor had ever hated to wander the cool paths of reason, where the heart grew dark and silent and eventually ceased to sing altogether. It had happened to Celegorm and Curufin; it was happening to Maedhros.

“I believe the children will serve us well,” he said at last.

In the beat of quiet that followed, Maglor hoped he had been wrong and would be rebuked for his insolence. But Maedhros, who had sworn never again to take hostages, nodded and said, “Proceed.”

How easily the rest unravelled. “They are the heirs of the Houses of Nolofinwë and Elwë, and the heirs of Bëor and Hador and Haleth. I do not know what will come to pass, but should they grow to manhood sympathetic to our cause…” Maglor trailed off. He looked over his shoulder at the carriage, where Elros sat upright beside his brother and they shared a wafer between them. He looked back to Maedhros, and realised he too had been watching the children. Maedhros swallowed and cast his eyes at the ground. Perhaps his reasoning was not so cold. “Perhaps,” he said aloud, “in some way I cannot foresee, they will be our hope.”

Maedhros lifted his chin. “Very well,” he said. “Care for them well. Love them, as I know you can, and perhaps they will in time love you in return. But do not speak of hope.”

“Thank you,” Maglor breathed, a rush of relief. His knees nearly gave way beneath him. “I will not fail you. I swear I will not fail you.” The urge to move, to touch was too strong. He embraced him. “I will not fail you,” he repeated into the curve of Maedhros’ shoulder, cheek pressed to the cold metal clasp of his cloak. “I will not fail them.”

Maedhros did not return the embrace, but neither did he push Maglor away.

Maedhros stood upon a hill watching the long caravan of Maglor’s host retreat south: a grey snake winding through the golden fields. The sun curved west behind them. Beyond, the woods of Taur-im-Duinath spread across the horizon like a vast canker.

Such, also, was the shape and colour of the future Maedhros foresaw when he searched his heart.

“Tell me, Lisgon,” he said to his captain beside him, “do you think we will see them again?”

Lisgon watched the host for a long time. “Not all,” he said at last.

“My brother?” Maedhros asked.

“Aye.”

“And Elwing’s sons?”

“That I cannot see, my lord. But I think if Maglor lives, so will they.”

Chapter End Notes

Thank you to sallysavestheday for the helpful beta, and to Melesta, cuarthol, and Ettelene for the ongoing support in writing.

Sick and Weary

The host pauses for rest on the eaves of Taur-im-Duinath. Dornil learns some disturbing truths about Maglor. Gwereth does her best to care for Elros and Elrond while struggling against her own grief and anger.

Read Sick and Weary

A shriek rose from the forest. Dornil’s head whipped towards the sound.

Nothing but an elf-child, her finger pricked while gathering in a thicket of berries. A mortal woman knelt to examine the cut, then treated it with a kiss. The child scurried off to rejoin the others. They were Sindar and Noldor, Edain and Easterling. Not even at thriving Ost-nu-Rerir in the heady years before the Sudden Flame had Dornil witnessed cultures moving so easily between and among each other. The refugees of Sirion were as a tapestry of myriad colours and fibres.

Dornil resumed the rotation of her pestle, grinding to a powder the beech nuts she had collected that morning. It was not a proper lembas preparation, for if any pure strain of Yavanna’s seeds remained they were with women of higher birth and nobility than Dornil. She had only accepted the role of a Breadgiver begrudgingly. Neither Hithlum nor Himring had ever had a queen to dole out waybread with regal airs, but on those rare occasions when Maedhros deemed it politic to observe tradition, the duty had fallen to Dornil wife of Caranthir; then Dornil set the bloodied hands of a kinslayer to grinding of corn and kneading of dough.

When Maglor ordered their rations distributed equally among the host, he said nothing one way or the other of the lembas — so Dornil eagerly broke with tradition and passed it out among the mortals, who had greater need of it than any Elda. They had looked on her with surprise and confusion, even awe, the first time she had distributed packets of the storied waybread, and she had credited the decision to their generous leader.

Dornil allowed that Maglor may have been right to take them into their number. For now, they seemed mollified, even contented. No murmur of discord or defiance had been marked on the road to Taur-im-Duinath. A tightly knit people, they did not make space for their conquerors in their midst, but nor did they seem to wish them harm. If any did, they guarded it deep where not even the sharpest elven mind could uncover it. But for the occasional choked sob under the veil of night, the people of Sirion walked, spoke little, and carried on.

When the host reached the eaves of the forest, Maglor had ordered four days’ rest. Scouts were sent ahead to chart their course while the rest repaired and washed clothing, took inventory of their supplies, tended to injuries, and foraged for food.

Taur-im-Duinath was a strange forest. So dense with vegetation, pressing out to its very edges, as to seem untouched by any creature that fed upon things that grow. Indeed, besides small stream-dwellers and the occasional bird flitting in and out of the crowns of ancient trees, they had seen no animals. Strangest was that much of what lived here was unknown elsewhere in Beleriand. The forest, vast and deep and verdant, was a world unto its own. Silent, some called it, and by day it lay quiet indeed, its thick growth swallowing the chatter, the whinnying of horses, the scrape of the whetstone, the fall of water from wrung textile.

The sounds, too, of children laughing. Glancing up from her work, Dornil noticed the berry-gatherers’ baskets had been forgotten in favour of a game of hiding and chasing through the understory. Dornil’s eyes rose to the darkening underbelly of the clouds. Dusk was coming on.

At night, Taur-im-Duinath awoke. At night, the forest threw back echoes of the day’s noises in strained, shrill tones. Noises that swirled and churned in the mind long after they had died, turning, turning until out of the confusion of sounds voices rose. Voices speaking, shouting, singing.

Screaming, as the child had done when pricked by the bramble. The pestle slipped from Dornil’s grip, scattering the flour over the mortar’s rim. She cursed. The loss was negligible; it was the stumbling of her thoughts that unsettled her.

She would not go mad. There were no voices in the forest. They were phantasms; delusions born of weariness. They could be silenced. She had only to retake the reins of her errant mind.

Her hands trembled. She set the mortar and pestle down on the wagon she was using as a work surface and gripped one of its side panels to steady herself. She felt a familiar presence approaching from behind.

“My lord,” she said, greeting Maglor with a look over her shoulder.

He squinted into the sun, some trace of a smile behind it, then perched himself at the end of the wagon.

He spoke low, with a wry edge, in Quenya. “How much longer, I wonder, until we forgo such titles? How many followers must a man lose before he is no longer a lord?”

Dornil huffed and shook her head. Formalities between them had begun to flake away as soon as their host departed Sirion, such that the sort of friendship they had not known since the days of peace, sitting round the hearth in the opulent chambers of Barad Rerir, had sprung up from the ashes of their helpless plight.

“Do you ask out of fear of losing your titles, lord,” she asked good-naturedly, “or eagerness to be rid of them?”

Maglor’s expression firmed, considering her question. “I know not. One and then the other, I suppose, or both at once.” He crossed his arms and regarded her. “I guess that you believe it is the latter.”

“I do,” Dornil said. Something in his manner made her bold. “Was it not your intent in counselling Maitimo to join the folk of the Havens to us that he, not you, should lead them? Ever have you wished to make him a king, and ever has he refused that title and donned the mantle of leadership only grudgingly. Can you truly be surprised he gave this host over to you?”

Maglor hummed and did not answer. She did not know if his capitulation pleased or disturbed her.

Dornil watched and waited as his eyes darted from place to place, observing the activities of their camp. Then he said: “Does it not weigh on you?”

“What?” Dornil asked.

“That these people have followed us.” He looked at her. “Do you not wonder why?”

Dornil had always thought it indulgent to chase after such unknowable questions. How could one ever truly know the inner workings of another’s heart?

“Because you invited them to,” she replied plainly. “Is it not what you wanted?”

“They might have refused,” he said. “They might have turned back on the road, but none have done so.”

“Their home is destroyed,” said Dornil. “And we are few but we are strong. We command the last fortress that has not fallen into enemy hands.”

“What of Balar?” Maglor asked.

“Balar is a refuge, not a stronghold, and it is defended by the mercy of Ulmo only. There is no reason one Vala might not overcome another. Moreover,” Dornil said, her voice edged with bitterness, “the Valar are fickle and may withdraw their protection at any time. This you know as well as I. Perhaps others have come to see it also.”

Maglor nodded. “I have thought the same.” He paused and threaded his fingers together across his lap. “Though, in truth, I find myself asking again if Moringotho only waited—”

A shriek cut off his words and he stood, hand leaping to the hilt of his dagger. Dornil’s own alarm was quelled by observation of his: the ripple down his jaw, the throb of his pulse beneath it, the tightness of his shoulders. She could almost feel him straining to master his impulse as he released his hold on the dagger’s hilt.

It all passed in the space of a moment, but it was enough for Dornil to know. He heard them: the voices in the forest. Were they both mad? Was it that had led him to doubt his fitness for leadership?

“I think I understand,” she said quietly. Then when he looked sidelong at her, “Do not let it overcome you. They are not real.”

Maglor’s mind — which she had seldom dared trespass since the battle, for it was dark and unwelcoming — opened to hers, seeking confirmation of her meaning. He found it in shared memories of wailing and crying.

“Who do you think they are?” he asked.

“No one,” Dornil replied hastily. “It is as I said. They are not real.”

“I do not think so.” His eyes flickered, the light within made brighter and more immediate by the deepening dusk. “They are souls.”

“They are not. They are figments of the mind.”

“No.” He shook his head. “I thought the same when first I heard them. It is what I want to believe. But yestereve I went to them. I ventured into the forest.”

“My lord,” Dornil interrupted, “you should not wander alone.”

He waved her off. “Has your belief in me fallen so far you think I cannot ward off a few houseless spirits?” His tone aimed at levity but only wavered more for the effort.

Dornil frowned. It was not the imagined spirits she worried about. But it would likewise be an affront to suggest Maglor was not capable of overcoming and subduing any one of their host. It was not them Dornil feared, either. What she feared, she realised watching him in that moment, was that he would not defend himself at all.

She said nothing, but Maglor was unwilling to let the subject rest. He said, “I guessed you heard them when I saw you startle at that child’s cry.”

“Then why did you not begin with that?”

“I suppose I thought you might think me mad. Or that pride might cause you to equivocate, lest I think you mad and unfit for duty.”

Dornil bristled. “My duty is to truth before pride. I would not equivocate, lord. I have never lied to you. I tell you truthfully that the sounds in the forest are not spirits.”

Maglor’s face was half-obscured, angled towards the woods, but Dornil saw how it quivered. How he blinked rapidly. He was like a heart cut open and raw, still beating, and it filled Dornil with the urge to flee. For duty, she did not; but she could not bear to look such transparent pain in the face.

She watched her trembling fingers instead.

Of course Maglor, maker of laments, had been repentant from the first blood drawn at Alqualondë. Dornil had ever respected his strength in balancing repentance and perseverance. Repentance was dangerous, though, for how closely akin it was to guilt. Guilt was the poison that had wormed through Maedhros’ spirit until he was nothing but the vessel, hard but hollow, that had once housed a heart of fire.

Maglor’s guilt, Dornil saw now, had been a sleeping snake coiled at the bottom of a jar. But when Maedhros had forced their separation at Sirion he had lifted the lid. Awoken his brother’s guilt, given it room to rise, escape, and hunt.

Dornil had little faith in her ability to tame it.

“My lord,” she said, “I beg you. Hold your tears.”

Maglor sighed heavily and clasped her wrist, guiding her hand away from where she clung to him. She had not even realised she had reached for him. “Thank you, sister,” he said.

Dornil tensed, taken aback; he had seldom named her thus. But even as he did, he walked away. He whistled a series of three notes and one of the horses roaming freely in the tall grasses lifted its head in answer. Dornil understood, as the animal trotted to his side, that she was not the sort of companionship her lord needed.

“There!” said Gwereth. “How does it feel?”

Seated on the carriage bench, Elros examined his boot.

“Can you thank Embor for mending that?”

Embor leaned forwards to meet the child’s eyes but Elros continued to stare at his foot. The sole had come loose three days before — it had taken that long to get Elros’ consent to have it repaired. Gratitude for the repair was, perhaps, too much to ask. Gwereth stole a glance at her friend and returned his smile with a quirk of her lips. She had not wholly forgiven him. When he had first found them among the host, harsh words had passed between them. How could you, she had rebuked him, willingly follow the sons of Fëanor?

“I owe my life to them,” he had said. “Had it not been for Lord Maglor my grandsire would not have escaped the field of Anfauglith, nor been able to save my mother and me.”

Gwereth had spat on the ground at his feet. “They would not have hesitated to kill you in Sirion.”

“They might have tried,” Embor had said. “And I would not have hesitated to slay one of theirs to defend a friend or kinsman. It is the way of war.”